Rear-engine Mercedes-Benz vehicles of the 1930s

- Rigorous realisation of innovative vehicle concepts

- Body design polarised in appearance

- Automotive industry of the day injected with important new ideas

Stuttgart – In 1934 Mercedes-Benz braved public opinion with a revolutionary vehicle concept, the 130 model. It was a bold move, since never in brand history had there been a production rear-engine car. Indeed, the entire history of the automobile, which by then spanned almost half a century, had seen very few rear-engine vehicles.

The starting point for the development of the 130 model was the difficult economic situation of the early 1930s and, in particular, the hoped-for mass motorisation, in which all automotive manufacturers were keen to have a slice of the action. This forced all of them to develop smaller and more affordable vehicles – the Mercedes-Benz brand, in particular, was reputed for producing mainly elegant and expensive models. Germany increasingly focused on the concept of the Volkswagen or ‘people’s car’, a designation which at the time denoted a category and general orientation rather than a specific vehicle.

Daimler-Benz AG did not blind itself to the requirements of the day, however, producing instead a fundamentally new concept, the rear-engine car. The principle reasons, viewed from its own perspective, were documented in the original sales brochures of the 1930s: a rear-mounted engine permitted better use of space. In cars with a relatively short wheelbase, this not only afforded passengers more leg room, it also improved comfort by creating optimum springing between the axles. In addition, the entire drive unit could be focused in a single unit and required no propshaft, giving vehicles the additional benefit of reduced weight and transmission losses.

It was perhaps to be anticipated that although the concept underwent continual refinements over the years, finally reaching maturity in the shape of the Mercedes-Benz 170 H of 1936, ultimately the rear-engine car never really caught on. What follows on these pages, therefore, is a fine example of the consistent application of progressive vehicle concepts throughout the long history of Daimler AG.

Launched by the then DaimlerChrysler AG in 1998, the smart city-coupé, known from 2004 onwards as the fortwo, was also based on the basic idea of a rear-engine vehicle, with optimum use of space and rigorously advancing the concept in the form of a two-seater city vehicle.

The 130 model has the honour of being the concept that took rear-engine design to a new level and made it more widely known, following its earlier implementation in a few individual mini cars – even before the car that would later achieve fame as the “VW Beetle”.

The first Beetle prototype did not get under way until October 1935. In 1937 Daimler AG was commissioned to build a further 30 prototypes at the Sindelfingen plant for the purpose of more intensive testing. Volkswagenwerk GmbH was founded in 1938, although with the outbreak of war, series production of the Beetle did not begin until 1945. The rear-engine vehicle finally went on sale to the public in 1946, around twelve years after the Mercedes-Benz 130.

A successor to the 130 model appeared in 1936. As the only rear-engine model available, the Mercedes-Benz 170 H was unique in carrying the letter “H” (for “Heckmotor”) in its model designation, in order to distinguish it from the front-engine Mercedes-Benz 170 V presented at the same time. The 170 H, which remained a part of the model range until 1939, put an end to many of the disadvantages of its predecessor, and offered much improved handling characteristics.

The two-seater Mercedes-Benz 150 with coupé body was also entered for the “2000 km through Germany” event of 1934. This car was based on a mid-engine concept, but nevertheless ranked alongside these distinctive vehicles. Designed specifically for sports events, it played a special role, since the 130 and 170 H models were passenger cars for everyday use. The open-top variant of the competition car, the Mercedes-Benz 150 Sport Roadster, subsequently made its debut at the IAMA in Berlin in 1935. It became part of the official sales range and was offered until 1936 – although built only in extremely small unit numbers.

The rear-engine models were the rigorous realisation of a technical vision. Part of this rigour also involved body design, for with a front radiator no longer required the entire vehicle could now take on a different shape. The models therefore differed fundamentally in appearance from the traditional front-engine vehicles, which – particularly in the case of Mercedes-Benz – had traditionally been heavily determined by the classical, almost iconographic radiator grille.

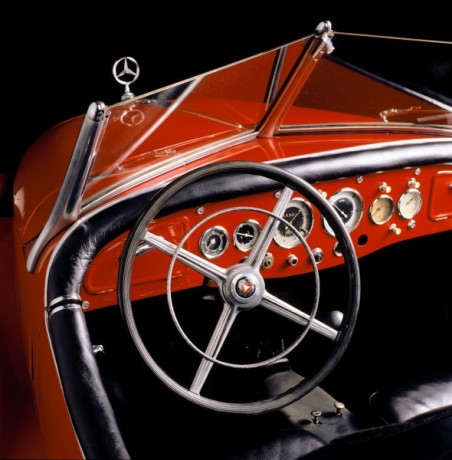

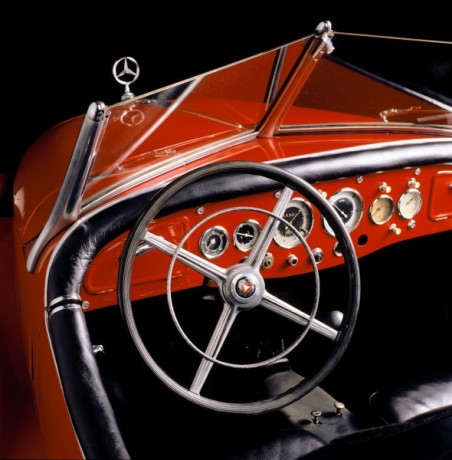

Now, the front end of all rear-engine vehicles appeared rounded, some with three-pointed star mounted inside a circle (130 model), others with a three-pointed star without circle (170 H model), and yet others with the free-standing Mercedes star (150 model) still familiar today.

Without doubt, these divergences from traditional design concepts played a significant part in the failure of rear-engine vehicles to gain the expected foothold in the market. But when one looks at these cars today, particularly the 170 H model, it is impossible to deny their progressive nature – all the more apparent when they stand alongside other cars of their generation.

As a result of their weight distribution, rear-engine cars are often criticised for poor handling characteristics. If corners are taken too quickly, there is a tendency for the vehicle to oversteer – in other words, for the rear end to slide towards the outside of the turn. Since the laws of physics are at the root of the phenomenon, it is a tendency that exists in rear-engine vehicles of all manufacturers.

Contemporary driving reports on Mercedes-Benz vehicles tested this tendency and were not sparing in their criticism. But they also said that drivers could – and indeed had to – adjust to this phenomenon in order to drive safely at all times.

It was also noted that in the 170 H, a late evolutionary stage of the rear-engine vehicle, handling characteristics were more balanced thanks to a comprehensive range of design measures. And compared with its counterpart with front-mounted engine, the 170 V, the 170 H even came off better in terms of suspension comfort, noise, drag and performance.

In the sum of their qualities, the rear-engine vehicles were also in line with the traditional Mercedes-Benz claim of giving customers the best whatever the vehicle model. As such, these vehicles offered active proof of the technological leadership of Daimler-Benz AG.

The call for a smaller Mercedes-Benz

- Various prototypes developed at an early stage

- The Mercedes-Benz 170 of 1931 is an important step

- Another issue for the industry of the day: the Volkswagen Project

The second half of the 1920s was a period of innovation in automobile technology. Many engineers began freeing themselves from the still popular designs based on the model of the horse-drawn carriage, with box frame, rigid axles and leaf springs. Instead, they strove towards new solutions such as independent suspension and high-rigidity frames.

The plans of Daimler-Benz AG fitted into this period of technological progress, for shortly after the merger of Benz & Cie. and Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft in 1926, the new company returned once again to a latent topic – development of the bottom end of the model range. Several designs for smaller vehicles with displacements of 1.3 litres and 1.4 litres were created under Ferdinand Porsche’s leadership as chief engineer; some of these were also built for testing purposes.

In 1926 these included eight prototypes (W 01 series) with a 1.4-litre six-cylinder engine and an output of 18 kW, and in 1928 a total of around 30 test vehicles (W 14) with a 1.3-litre four-cylinder engine, which also developed an output of 18 kW. However, both cars toed the conventional line with side-valve engines and rigid axle chassis. They never reached the series production stage for economic reasons.

In 1931 Daimler-Benz AG then brought to market the Mercedes-Benz 170 (W 15) developed by Porsche’s successor Hans Nibel. Although this car proved a great success, there was still a long way to go. Europe did not escape the impact of the global economic crisis during the early 1930s, and realising the pressing need for an even more affordable vehicle, the company once again opened up a serious internal debate on extending the model range further downwards.

Chairman of the Board of Management Wilhelm Kissel and chief engineer Hans Nibel, in particular, warmed to the challenge of this issue, since before the merger at Benz & Cie. the two had enjoyed success with smaller vehicles, including the 6/18 hp Benz of 1911. They were also supported by Max Wagner, Head of the Design Office, and his designer Josef Müller.

Smaller vehicles already in the family for some time

In his memoirs, published in 1990, Müller wrote: “Questions had been raised within the company for some time [about the possibility of a smaller car], since the days when we could sell only large and prestigious vehicles seemed to be gone for good; we were on the brink of a new type of popular motoring. The four passengers deserved to be given the best suspension possible between the axles.”

The young Josef Müller was one of the avant-garde of automotive engineers striving for fundamentally new technological innovations. After completing his diploma at the Technical University in Munich, he joined the “CB”, as Max Wagner’s construction office (Construktionsbüro) was known, and set about tackling new challenges with creativity. In 1932, for example, he pressed ahead with the advance development of a design for cars with a 1.2-litre engine.

Between late 1931 and 1934 the department also came up with numerous designs for small four-seater rear-engine cars with air-cooled boxer engines and liquid-cooled three- and four-cylinder engines, some of which were transverse-mounted above the rear axle. At the same time, however, vehicles were also produced in the same size category with front-mounted engines and front-wheel drive – a pioneering combination at the time. Kissel authorised the front-engine designs in order to have a replacement for the rear-engine car if required.

Lofty claim of technological leadership

Kissel’s lofty claim of technological leadership applied to his company as a whole; but if a smaller Mercedes-Benz was to live up to the claim, it had to provide actual proof of the technological leadership of Daimler-Benz.

This became plain in fundamental comments made by Kissel on another occasion: “Although we have to be prudent with our money in these critical years, it is necessary, now more so than ever, to show the world that the spirit of Gottlieb Daimler and Carl Benz lives on in us, and to prove that Daimler-Benz AG is determined to defend its inheritance.”

The level of urgency accorded the project is today evident from discussions that Kissel had with the Board of Management and other key figures during the International Automobile and Motorcycle Exhibition (IAMA) in Berlin in 1933. He said: “We are facing the situation that our position this year [1933], as well as our plans for a 1.3-litre car, would be considerably enhanced, particularly if the general outlook does not significantly improve and instead the trend towards smaller, more economical and cheaper cars sooner or later becomes more marked than hitherto.

The benchmark remains the position that our sharp focus must be on developing technological progress, because otherwise another company may succeed in producing a car with driving qualities at a price that could thwart our intentions in respect of the 1.3-litre car.”

So the decision to build the Mercedes-Benz 130 had already been taken some time earlier. It made its debut in 1934 and was based on what was for the time a revolutionary concept. As a rear-engine car, it almost literally turned back to front most of what until then had been considered conventional basic car design.

In June 1933 Kissel predicted a change in the market situation. The minutes of a meeting of the Board of Management noted: “On the issue of whether the larger models will suffer as a result of the

1.3-litre model, Mr. Kissel observed that model orientation was moving downwards and that customer numbers for cars priced over 4,400 Reichsmarks were becoming increasingly smaller.

Larger cars, including the six-seaters, would therefore inevitably become less important.” Another of Kissel’s remarks is also particularly striking set against the historical context: “As a further aspect for present considerations, it should not be forgotten that a price code is to be introduced. Dealing will disappear, just as haggling will be eliminated. But with fixed prices our share in the RM 4,400 car class will probably drop from 10 % to 6 % without the 1.3-litre. Therefore, if we are to maintain and consolidate our current market share, the 1.3-litre car must be produced.”

Kissel also justified the decision in favour of the new model on a different occasion, saying that: “in view of the rapidly sinking market, there were two possibilities: Either to so cheapen the 170 model that the sales price could be set much lower, or to reach out at the bottom end of the sales range by creating a new model. The second solution – to introduce the 1.3-litre car – was the only logical option.”

But voices calling for practical small automobiles could also be heard in the public arena. One of the untiring advocates – along with the designers Edmund Rumpler, Hans Ledwinka, Béla Barényi and Carl Slevogt – was the journalist and editor-in-chief of the trade magazine Motor Kritik, Joseph Ganz, who had himself designed and built a number of mini cars with rear-mounted engines and independent suspension, such as the Standard Superior.

Ganz, who maintained close contact with Kissel, but also with Nibel and Jakob Krauß, the head of the test workshop, wrote in an earlier observation: “In Untertürkheim, where I have been pressing for the design of a larger rear-engine car since 1930, the matter was taken in hand in earnest. In order to overcome the most recent preconceptions, in winter 1931 the Maikäfer [Ganz’s rear-engine mini car design] was brought by truck to Untertürkheim and given a thorough workout for a day by the Board of Management.

At the same time, following completion of the uprated Maikäfer, the Standard Superior, at the Standard-Fahrzeugfabrik in Ludwigsburg, the Mercedes rear-engine car, the current 130 model, was developed along basically the same principles by designers at the plant.”

In 1930s Germany there was also another project that was the talk of the automotive industry – the Volkswagen or People’s Car. This term was used at the time to denote a category and desired orientation rather than a specific model. Volkswagenwerk GmbH only started series production of the vehicle that would later become famous as the “Beetle” in 1939.

Kissel pushed for involvement in the Volkswagen project and demanded that “[…] in spite the 1.3-litre car, design of the so-called Volkswagen and the necessary preliminary studies should be pursued with all due despatch.”

The project was still exerting a grip on the Board of Management nine months later, when it was observed: “During discussions concerning the creation of a cheaper and smaller car, it transpired that Daimler-Benz AG was indeed in a position to perhaps bring out a vehicle in the 2,000 – 2,200 Mark price range, but that it would be inconceivable that our company could produce an even cheaper car.

The question of whether we should concern ourselves with the development of such a car was thus for the time being decided, to the effect that it must first commit itself to the Volkswagen problem. Since, in relation to the Volkswagen problem, Daimler-Benz AG had certain employment obligations and declarations concerning these from the Führer, our company must maintain its role at the centre of this matter.

As experience to date has shown us unable to create something positive ourselves, the decision was made to bring together all German passenger car manufacturers in order to see whether, by pooling all resources, a solution to the Volkswagen problem might be found.”

At the core of this statement by Kissel is the recognition that it was impossible for a single company to manufacture and produce for sale a vehicle with a price tag of 990 RM (Reichsmark), as demanded by Adolf Hitler, by going down the private sector route.

At the same time, it should not be forgotten that vehicle sales also involved the manufacture, stocking and distribution of replacement parts and the provision of a service network. This was particularly true in view of the imminent rationing of raw materials and the segmenting and assignation of specific vehicle categories, in which individual companies would be required to operate.

These were difficult times. But Daimler-Benz confronted them by going on the offensive. The new small Mercedes-Benz with rear-mounted engine was a courageous step forwards. Based on a fundamentally innovative concept, it injected important new ideas into the automotive world of the 1930s.

Mercedes-Benz 130 (W 23 series, 1934 – 1936)

- Fundamentally new concept calls for a new design

- Body has favourable aerodynamic design

- Testers praise comfort and handling characteristics

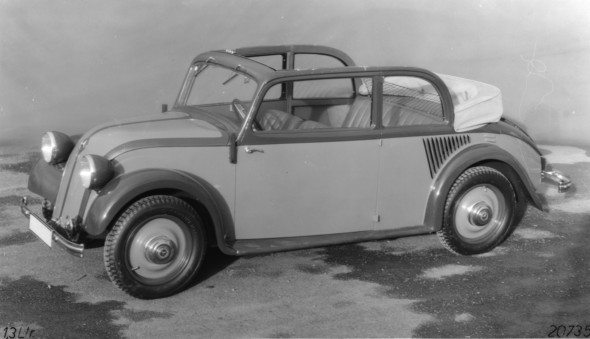

The Mercedes-Benz 130 (W 23) was unveiled in March 1934 at the IAMA in Berlin. At the time of its presentation it was not only the smallest production passenger car, the first rear-engine car and the first four-cylinder model from Daimler-Benz AG, but also the first volume-produced German rear-engine car, leaving aside various micro cars. Officially it never bore the letter “H” in the model description, even though this was often used in internal plant documents.

The 130 model was of an entirely new design. An original brochure summed up the idea behind the vehicle: “Designing the

Mercedes-Benz 130 model has without doubt been one of the most interesting challenges ever faced in automotive design; this was to create a car with the ride characteristics of a large swing-axle model, the ride comfort of a modern mid-sized car and the running costs of a small car.”

The brochure also provided the reasoning behind the rear engine concept: “The engine has been positioned at the rear in order to improve spatial design, focus the entire powerhouse in one place and reduce weight and technology.” This offered three advantages: “First, the engine formed a closed and easily accessible assembly with the transmission, differential and rear axle.

Secondly, positioning the engine at the rear meant there was more space for passengers. Thirdly, the housing for all four passengers could be positioned between the two axles, making driving significantly more comfortable.”

The reduced weight came, for example, from the fact that a propshaft was no longer required; this in turn cut transmission losses and thereby improved yield from the engine output.

In 1934 another brochure advertised the vehicle’s merits: “This model is a quality utility vehicle suitable for a broad circle of users; thanks to its use of patented swing axles front and rear, its low-slung design, rear-positioned engine, broad track and favourable weight distribution, it boasts incomparable handling characteristics.”

Those who approached the Daimler-Benz stand at the IAMA expecting to be welcomed by the familiar sight of the Mercedes-Benz radiator grilles was in for a surprise. Visitors encountered a new and very unfamiliar face, one which signalled the start of a new era in vehicle design.

The only indication that the visitor was at the right stand was the traditional Mercedes star. The new, smaller Mercedes-Benz, with its still largely unfamiliar rear-mounted engine, a four-cylinder assembly and new design proportions proved a source of considerable interest and reflection. Compared with its narrow-tracked and high-wheeled classmates, this stocky, untippable vehicle stood on its four individually sprung wheels with great self-assurance.

The new model aroused curiosity and the expectation of being bigger inside than out. It did not disappoint, for its surprisingly spacious interior was not much smaller than that of the six-cylinder

Mercedes-Benz 170, previously the smallest vehicle made by Daimler-Benz. The large, unsplit windscreen provided an unrestricted view to the outside. In combination with the folding front seat rests, the two large side doors gave excellent access to the raised rear seat bench, behind which there was still room for a sizeable suitcase.

The front bonnet housed the horizontally stowed spare wheel along with tools and smaller travel accessories. One exceptional feature for the time and vehicle category was the car’s standard-fit heating system.

The 1.3-litre four-cylinder engine was a new design with side valves and updraught carburettor, developing 19 kW at 3400/min and a top speed of 92 km/h. That made the vehicle marginally faster than the 170 model. It cut a fine figure with what were considered for the day highly aerodynamic lines.

With a drag coefficient of cd=0.516 it was on a par with a Mercedes-Benz 230 SL of 1963 with hardtop, which achieved figures of cd=0.515, and much better than the popular pre-war Mercedes-Benz Stuttgart with cd=0.662. Even the drag coefficient of cd=0.498 for a 1966 VW Beetle, which had the advantage of flush-mounted headlamps, was not so significantly better as one might have expected after a period of 32 years.

The 30-litre fuel tank was located to the right of the engine. Positioned in front of the rear axle for better axle load distribution, the three-speed transmission also featured a fourth option, which, in line with the trend of the period, fulfilled an overdrive function. This overdrive was preselected without use of the clutch and selected by releasing the accelerator. The overdrive automatically engaged as soon as the accelerator was depressed. Hydraulic four-wheel brakes, another feature that was by no means standard for this class of vehicle at the time, provided reliable braking.

The engine offered impressive displacement reserves and in the 1950s reached both its highpoint and endpoint as a 1.8-litre engine in the 180 and 170 S-V models.

The 130 model was available as a two-door Saloon and a two-door Convertible Saloon. For special official purposes, there were also versions as open-top touring cars and Kübelwagen. In addition, plans were made to offer the chassis alone for special bodies, but there are no surviving records that prove this actually happened.

The roof of the saloon, pressed in a single piece, was not commonplace at the time. Most car roofs of the day had a fabric-covered wooden frame supporting the large central section. At the Sindelfingen plant the company had to purchase a special hydraulic press with corresponding mouldings to produce the large, new pressed part.

The designation Convertible Saloon characterises the second vehicle type precisely. The folding fabric soft-top opened up the roof and rear section if required, while the vehicle’s side walls remained fixed.

Even before the date of the official unveiling, it had been agreed not to allow the 130 model to stand alone in the model range, but to develop it as part of a family of rear-engine vehicles. Already under discussion were a model with 1.6-litre engine and four doors as well as a sports car.

New concept calls for a new design

For the rather conservative-minded Mercedes-Benz customer, the exterior of the new car required complete readjustment, since the rear-engine vehicle no longer needed the classic, front-mounted radiator – and Daimler-Benz resisted the temptation to give the vehicle the appearance of a conventional front-engine car by fitting a dummy radiator. After considerable testing and in-house deliberations, the decision was taken to proceed on the basis of a clear rear-engine design. This also included the addition of an encircled Mercedes star embedded in the raised beading that ran up and over the front bonnet.

Another distinctive element of the new vehicle’s look were the intake louvers in the side panels below the rear side windows, which channelled air towards the radiator positioned above the rear axle. The rounded engine lid featured three longitudinal vents with cover plates, which gave the vehicle a distinctive and unmistakeable rear aspect.

Thus the 130 model was unveiled to reveal an entirely unique design, lending it what was considered a thoroughly avant-garde appearance for the time – although this did little to boost the vehicle’s market success. Nevertheless, the rigour with which the decision to pursue such design independence was taken earned considerable respect, not to mention tributes published in the contemporary press. For example, in issue 53 of Motor und Sport in an article entitled: “Form? Reflections on the new MB 130”, Wolfgang von Lengerke wrote in 1933:

“A familiar shape is always attributable to tradition. But tradition presupposes there is a process of development. However, since what we are dealing with here is an entirely new and viable shape for motor vehicle production, it would be unreasonable to expect the design at this stage to have already reached classical perfection. The possibilities that lie at the heart of this commonplace development of the future are best demonstrated by the feeling one has when one rides in this car.

It has comfortable seating, and the large, broad windows offer an unimpeded view over the surrounding countryside. The suspension is so soft and accomplished that it is barely possible to determine the nature of the road surface. Those who perhaps harbour a dislike for the vehicle’s exterior, because it deliberately sets a revolutionary idea against hitherto traditional formal elements, will be forced to recognise its certain future supremacy as soon as they take a ride in it.”

Contrary to later frequent assertions, the 130 model, as shown by the company’s production statistics, enjoyed considerable success. Records show that in the year of preparation for series production, 1933, precisely one example of the two-door 130 Saloon was built, by 1934 numbers had risen to 2,205 units, offered for sale at a price of 3,425 Reichsmarks. 1,781 units (RM 3,680) were built in 1935, and another 311 units in 1936 (RM 3,200).

By way of direct comparison, in 1933 the 170 (W 15) had production figures for the four-door saloon of 3,130 units (RM 4,400). 2,508 units (RM 4,150) were produced in 1934, a total of 3,020 units (RM 3,950) in 1935, and 497 units (RM 3,950) in 1936.

Sales of the rear-engine car were perhaps all the more impressive, since the entirety of its design embodied a highly avant-garde concept that left many long-standing Mercedes-Benz customers with great reservations.

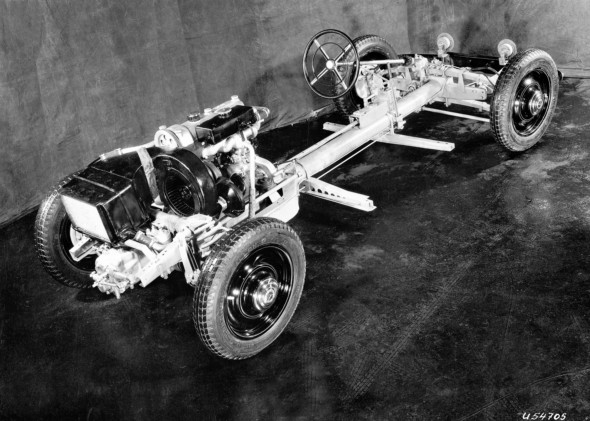

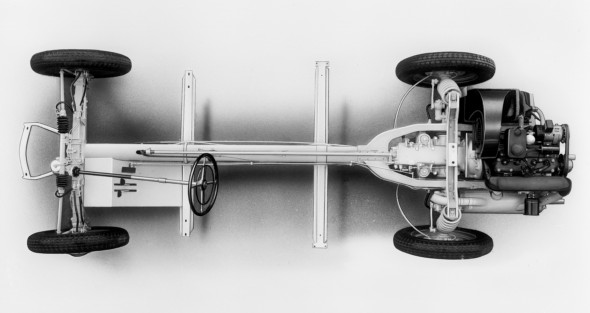

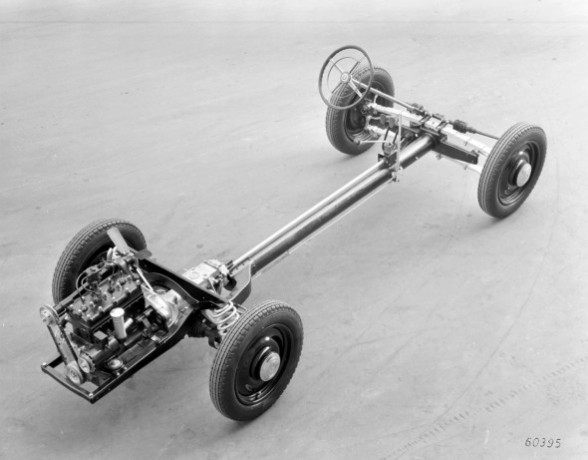

A fundamentally new design

For the 130 model a new tubular backbone chassis was designed, forked at the rear to accommodate the engine. The crossmembers to hold the body were mounted below the backbone chassis for a lower centre of gravity. The seats were positioned in the area of the car offering optimum suspension – between the axles. As with the 170 model, the front axle design incorporated independent suspension, two superjacent leaf spring packages which were attached to the front chassis crossmembers, and lever-type shock absorbers. The dual-joint rear axle had two coil springs.

As designer Josef Müller recorded in his memoirs, the original idea behind the rear-engine car is clearly attributable: “Max Wagner recalled his ‘Benz Teardrop’ with rear-positioned engine, actually a mid-positioned engine.” The design of this new vehicle was difficult – above all, because until then there had been no real lessons with rear-engine cars to learn from. Müller reported: “Using an experimental version with an air-cooled boxer engine we had already learned not to bolt the engine and transmission unit directly to the tubular backbone chassis, but instead to mount it elastically in a bifurcated frame and if possible for it to be water-cooled.

Unfortunately, in selecting the engine type, we gave in to the temptation to use the longer, if simpler, in-line four-cylinder unit rather than the short boxer engine. The first test drives were anything but satisfactory. The […] birth defect of the swing axle had a greater than expected impact in combination with the excessive rear-end weight. Nevertheless, after carefully tuning tyre and spring softness between front and rear axles and solving the noise problem, we succeeded in creating a serviceable vehicle out of what was initially a rather stubborn mule.”

Handling characteristics remained a subject for internal discussions. In November 1933, for example, the grave concerns expressed by Untertürkheim plant director Hans H. Keil during a technical meeting were recorded in the minutes: “Mr. Keil reported that both he and Mr. Uhlenhaut had noted the poor roadholding ability of the rear-engine car and that he harboured the gravest concerns for the vehicle model.”

Fine-tuning improves handling

The company nevertheless found technical solutions to improve the vehicle’s ride characteristics. For example, the fine tuning mentioned by Müller proved successful, as demonstrated by initial driving reports. The trade press was at first rather sceptical of the new vehicle, before recognising the efforts that had been invested and also the early stage of development of the concept. In the following account, journalist Joseph Ganz, who had the opportunity to drive a pre-series car before its official presentation, also considered the ride characteristics of the new 130 model:

“I had the opportunity to take the car recently for an extended test drive. In engine terms, the MB 130 rear-engine car behaves almost exactly like the MB 170 [with front engine]. Even the performance of the two vehicles is almost identical. It is interesting to note that when inside the car, the rather noisy engine is not in the least bothersome. Idling, acceleration and endurance: excellent.

And now to the most important aspect, its roadholding characteristics: In truth, the MB 130 is not a rear-engine car in its purest form. It is more a car with an “outboard motor” The engine is overhanging to the rear, causing undesirable tail weight.

This feature makes front shock absorbers necessary, which in a sense has removed the icing from the cake in terms of handling, as we have come to expect from uncompromising rear-engine cars. This results in shortcomings that irritate the sensitive driver, the connoisseur. But once one has overcome any feelings of disquiet caused by the sensation of floating the car gives, or the manner in which its rear end struggles to get round corners, and one then compares this car with any other front-engine vehicle, you will without doubt come down in favour of the MB 130. The suspension is unique.

There is absolutely no jolting. All that remains is a gentle rocking, rendering the journey a sheer delight. And steerability is just about perfect. The car reacts to every touch of the steering wheel. This is driving of the utmost refinement. Brakes soft and highly effective. Good visibility, excellent ventilation. No petrol odours in the interior.

In order to test the full potential of the rear-engine car, I drove on snowy and at times icy tracks on the Feldberg in the Taunus region, an area that has been almost completely abandoned by other motor vehicles in recent days. The four-day-old snow was still virginal. Only on one occasion did the car deviate by a few degrees from the intended direction – the result of a snowdrift – but I was immediately able to bring it back on track again. Otherwise it holds its line better than many others on a gravel track. The MB 130 is a quite remarkable vehicle. For me, it is way ahead of any other vehicle I know in this class. Nevertheless, there is still room for further development, by extending the wheelbase rearwards and shifting the weighty engine mass closer to the car’s centre of gravity.”

Ganz’s colleague Stephan von Szénasy gave the car a similar test rating in 1934 for the trade magazine Motor und Sport, writing in Test Report No. 105 in issue 14: “As with any car that breaks the mould, one takes a good long look before setting off on a test drive. The 130 model from Mercedes-Benz is innovative in every respect. A rear-mounted engine means having the bulk of the vehicle’s mass in your back. Theoretical considerations alone could not instil absolute confidence with regard to the design arrangement opted for by Daimler-Benz. Which renders the thoroughly positive appraisal that is the subject of this test report all the more impressive.

To a certain extent one is required with this car to rethink one’s approach to driving, just as with one’s first test in a front-wheel drive vehicle, and in particular where cornering is concerned. After half a day’s test driving in urban traffic, we headed out onto the open roads.

By the end of the first hour’s driving the car had clocked up exactly 67 kilometres, including the drive through Spandau and Nauen. Effectively that says it all. With the 130 Mercedes one achieves average speeds approaching those of the outstanding 170 model, even though the power source is an engine with a displacement 400 ccm smaller. In every respect, therefore, I have nothing but praise for the car’s performance. A top speed of 92 km/h – timed on the Avus – represents a far from everyday performance for a car of this size.

And so to roadholding? Under all conditions encountered – it was, nevertheless, only possible to test the car on dry roads – the Mercedes-Benz 130 demonstrated a very high degree of safety. Roadholding was excellent, so too was the car’s insensitivity to poor road surfaces. And as for cornering safety, this too deserves fulsome praise – so long as one has taken the trouble to acquaint oneself a little with the car’s idiosyncrasies, since it calls for a somewhat modified driving technique.”

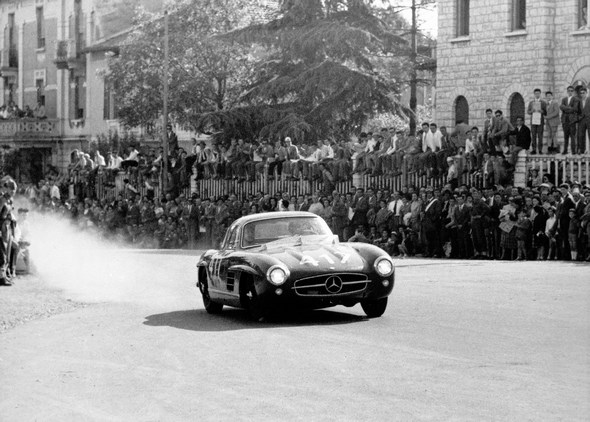

Six Mercedes-Benz 130 cars took part in the “2000 km through Germany” in 1934. Three of them reached the finish and were awarded one gold medal (for finishing in the allocated time), a silver medal (finishing less than 30 minutes over the allocated time) and a bronze medal (finishing less than 60 minutes over the allocated time). The brand was well represented at the event, which attracted entries from around 650 passenger cars, as well as from an equally large field of motorcycles: Taking part in addition to the compact rear-engine cars were also Mercedes-Benz SSK, SS, 500 K, 380, 290, 200, 170 and 150 models.

Model refinement with detailed improvements

In 1935 the new small Mercedes-Benz underwent improvements, above all in terms of body and interior equipment. For example, revisions were made to the instrument panel: two large circular instruments with ivory-coloured dials were positioned directly in front of the driver, and on the front passenger’s side was a large glove compartment with a clock built into the lid. The upholstery of the front seats was improved and were now easily adjustable thanks to a “quick adjusting mechanism” – the previous archaic solution involving loosening screws was now a thing of the past.

The rubber floor mats were replaced with carpet mats. At the front end beneath the A-pillars a vent was inserted for each footwell, recognisable on the outside by two slits above the right and left front wings. The tuning between springs and shock absorbers and the camber of the front wheels were altered in order to improve handling. Also under discussion was a more indirect steering system, although it remains unclear as to whether or not this was actually realised. Even before the start of the new model year the 130 model had been fitted with Vigot vehicle jacks.

In addition, modifications had been made to the front bonnet, which in this rear-engine car of course housed the luggage compartment. This front bonnet now no longer incorporated the vertical side elements, but instead rested on top. With the exception of the all-black variants, vehicles built in 1935 were mainly two-tone, the wings being optionally available in black or in the car’s second colour.

Remaining stock of the original variants were initially also available as “Model 34” and remained in the price list until July 1935, reduced by 225 Reichsmarks for the Saloon and Convertible Saloon. On the other hand, prices for the “Model 35” were positioned higher, at RM 480 and RM 500 respectively.

In October 1935 another technical modification was made to the 130, which permitted operation of the fuel cock from the driver’s seat. At the same time, the price of the so-called “Autumn model 1935”, which did not yet include this feature, was reduced by RM 580 and RM 600 respectively. A price reduction for the “Winter model 1935” introduced just two months later, on the other hand, paved the way for the launch of the successor model. In February 1936 the 1.3-litre car was replaced by the more powerful and, in many respects, redesigned 170 H model. The 130 remained on the price list as a discontinued model until February 1937.

The 130 was also linked to a further innovation, since it marked the start of foreign production at Daimler-Benz AG. In 1935 the first rear-engine cars were assembled in Denmark in response to a steep rise in demand there. All vehicle parts were shipped from Germany.

Mercedes-Benz 130 (W 23 series)

Cylinders: 4 (in-line)

Displacement: 1308 cm³

Output: 19 kW at 3400/min

Max. speed: 92 km/h

Production period: 1934 – 1936

Mercedes-Benz 150 Sport Saloon (W 30 series, 1934)

- A two-seater mid-engine coupé

- Designed for use in sports events

- Streamlined body reflects prevailing trends that made speed a principle

At a technical meeting of Daimler-Benz AG in November 1933, Max Wagner presented to Board of Management members Hans Nibel and Otto Hoppe and several directors a proposal for a mid-engine sports car. Designed specifically for sports events, the vehicle was to be given its first competitive outing in the 1934 “2000 km through Germany” race. Minutes of the meeting note: “During discussion of the rear-engine car itself, Herr Wagner presented a complete design for a rear-engine sports car, which, as generally recognised, has the potential to become the future German sports vehicle for broad sections of the population. It is a two-seater streamlined vehicle, in which the engine is positioned not behind but in front of the rear-axle unit.”

The design presented by Wagner was for a two-seater sport saloon – what would be termed today a coupé or sport coupé – with unusually efficient streamlining by the standards of the day. The finished vehicle bore similarities to the later VW Beetle of the post-war era. Distinctive features at the rear end included scoops in the roof section and numerous vents to provide fresh air for the engine. The Mercedes star was free-standing on the front bonnet.

The unusual feature of this design, compared with the Mercedes-Benz 130, was its use of the mid-engine concept, which is still used today in sports cars and in Formula One. The drive package of engine and transmission was rotated through 180 degrees in order to improve the distribution of masses between the axles. The engine was positioned in front of the rear axle, the transmission behind it.

Now Wagner saw his opportunity to introduce the concept of the mid-engine car at Daimler-Benz, a concept he had pioneered and realised a decade before in the Benz “Teardrop” racing car. At around this time, Ferdinand Porsche, who was of course familiar with these plans from his time as chief engineer at Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft and Daimler-Benz AG, was also in the process of bringing this concept to fruition, in particular in his design of the Auto Union P racing car.

The four-cylinder in-line engine was a largely all-new design. It had a displacement of 1.5 litres, in line with sporting regulations for the intended entry category, a twin carburettor and an overhead camshaft driven by spur gears. This was standard racing engine design at Daimler-Benz at the time. Engines for ordinary road vehicles, by contrast, generally featured the overhead valve system and updraught carburettors, a design that was not exactly conducive to optimum output and fuel consumption, but had the merits of smooth operation and reliability.

Sports vehicle with high-performance engine

The sum of these measures generated an output of 40 kW from the four-cylinder assembly – a sizeable rating for a 1.5-litre engine and one which highlighted an advance in engine design. By comparison, the four-cylinder engine of the 130 model provided 19 kW, with the six-cylinder 170 and 200 models developing 24 kW and 29 kW respectively. The drive unit of the 150 model was equipped with two final drive ratios and different transmission ratios for third and fourth gear.

The highest gear gave a top speed of 131 km/h. The wheelbase was extended by 100 millimetres compared with the 130 model, and the front track width by 30 millimetres. This sports engine was also used in several 150 model sports cross-country vehicles of the 1930s, although here it was front-mounted.

Fritz Nallinger allayed concerns that the 50 vehicles required for homologation would not be built within six months by using a considerable number of production parts from the 130 model – and sure enough, the company was able to take part in the reliability trial using the new vehicle.

For the 2000-kilometre trial, staged from 21 – 27 June 1934, six examples of the Sport Saloon version of the 150 model were built and used. They proved a sensation on their debut. An anonymous commentator wrote in the trade magazine Motor und Sport: “We had a number of surprises of a technical nature in Baden-Baden, [the start of the long-distance trial], for there were many new vehicle models on display that had been developed in secret.

Daimler-Benz arrived with a sensation in the form of a new rear-engine car equipped with an ohv 1 1/2-litre engine. The fact that the engine was positioned in front of the axle meant that useful space in the interior was lost, but this was more than compensated by the significant gains in handling. What is interesting about this sports car is its entirely closed, streamlined design. The new arrangement of the rear engine permits a particularly effective shaping of the car’s rear end.”

In addition to the 150 models, Daimler-Benz also entered a Mercedes-Benz 500 K streamlined coupé in the “2000 km through Germany”, a precursor of the later “Autobahnkurier”. The streamlined body reflected the circumstances of the time. The 1920s and particularly the 1930s witnessed a rapid growth in mass motorisation. Autobahns were built, and cars began to play an important role as a long-distance means of transport. It is no surprise, either, that speed became an associated principle – streamlined bodies and improved aerodynamics not only resulted in more kilometres per hour, they simultaneously embodied the very notions of speed and modernism.

Two of the six teams driving the Mercedes-Benz 150 models were forced to retire. The remaining four won gold medals, one of them with the later racing driver Hermann Lang at the wheel. A gold medal was awarded to those who completed the route in the prescribed time, since the 2000-kilometre trial was not a road race in which the winner was the car with the fastest time. The event was also the largest deployment of Mercedes-Benz 150 models.

The car’s most notable success came shortly afterwards, however, and remains relatively unknown. At the Liège – Rome – Liège long-distance race in late August 1934, Hans-Joachim Bernet took the special award for best-placed closed car, having led the entire field from Rome to Pisa and finished without penalty points.

The final whereabouts of the six Sport Saloons remains unknown.

Mercedes-Benz 150 Sport Saloon (W 30 series)

Cylinders: 4 (in-line)

Displacement: 1498 cm³

Output: 40 kW at 4600/min

Max. speed: 131 km/h

Production period: 1934

Mercedes-Benz 150 Sport Roadster (W 30 series, 1934 – 1936)

- Open-top Sport Saloon variant

- Public premiere at the 1935 Automobile and Motorcycle Exhibition in Berlin

- Car now in possession of Daimler AG is thought to be the only surviving example

Following the success of the 2000-kilometre event in 1934, in August Kissel stressed “[…] that it was absolutely essential to bring out a small, streamlined sports car by the spring of 1935.” Thus in November 1934 the Daimler-Benz Board of Management decided to build two Sport Roadsters based on the Mercedes-Benz 150 for the 1935 IAMA in Berlin. One of these was to be presented at the exhibition stand, the other to be available for test drives. Delivery of the production units was scheduled for May.

Like Wilhelm Haspel as Head of the Sindelfingen plant, the Head of Testing Fritz Nallinger stated his position with respect to the new Sport Roadster in January 1935, making mention in particular of the compressed-air radiator, which was later also used in the 170 H model, the two spare wheels mounted on either side behind the doors and the centrally mounted high-beam headlamp at the front end.

The body design of the Sport Roadster was fundamentally different form that of the Sport Saloon. As an all-new design, it bore several typical features of open-top sports cars of the day, including, for example, the swept split front windscreen and the two free-standing spare wheels mounted in front of the rear wings. Also highly distinctive was the pointed boat-like rear end with its two licence plate holders. A free-standing Mercedes star was mounted at the front end.

One sales brochure hailed the vehicle as a “thoroughbred sports car”, highlighting the qualities of the sports engine and its outstanding power-to-weight ratio. “Each hp has a load of just 19 kg! This explains how the 150 has acceleration in every gear – and virtually on a par with that of a supercharged car.”

In terms of technical design, including the engine, it was identical with the Sport Saloon. The compressed-air cooling permitted the use of a smaller radiator, since the cool air was forced through the radiator by a blower driven by the engine. The small rectangular radiator was mounted behind the engine above the rear axle.

Behind the seats was stowage space for both the lightweight, button-on soft top and small items of luggage. And the front bonnet could accommodate a large suitcase and the fuel tank. The 150 model was offered at the 1935 IAMA with a price tag of RM 6,600.

The Mercedes-Benz 150 Sport Roadster remained a part of the official sales range until 1936, but was only built in extremely small numbers. Records vary as to the exact number of units produced. One production statistic puts the figure at 20 examples. The statistics for bodies produced at Sindelfingen records just five examples – one in 1934, four in 1935. On the other hand, the order books show just two deliveries. But one thing is certain: the 150 model was not only one of the rarest cars from the Mercedes-Benz brand, it was also one of the most technologically innovative vehicles of its day.

One 1936 Roadster is in the possession of Daimler AG. It was purchased second-hand in the early 1950s with a mileage of 44,500 kilometres thanks to the intervention of former Board of Management member, Jakob Werlin. It would appear to be the only surviving vehicle of this highly innovative model series.

Mercedes-Benz 150 Sport Roadster (W 30 series)

Cylinders: 4 (in-line)

Displacement: 1498 cm³

Output: 40 kW at 4600/min

Max. speed: 125 km/h

Production period: 1934 – 1936

Mercedes-Benz 170 H (W 28 series, 1936 – 1939)

- Excellent ride comfort and outstanding performance

- Overall a highly sophisticated rear-engine vehicle design

- High price tag thwarts market success

As early as mid 1933 a more powerful variant with a displacement of 1.5 – 1.6 litres was being considered alongside the Mercedes-Benz 130 model. Six months later the plans became reality when it was decided to give the go-ahead for a 1.6-litre series to follow the 1.3-litre car.

Then in February 1936 the Mercedes-Benz 170 H (W 28) made its debut at the International Automobile and Motorcycle Exhibition in Berlin, superseding the 130, along with the 170 V model (W 136) which was built in parallel. This time the “H” for “Heckmotor” (rear engine) was used officially in the model designation, the identification now being necessary in order to distinguish the rear-engine car from the 170 V with identical displacement and front-mounted engine. As with its predecessor, the two-door 170 H came both as a Saloon and Convertible Saloon. An open-top touring car was not available.

One should explain at this juncture a set of circumstances that applied to both these 170 models – a situation that arose because the two series had been developed as 1.6-litre cars until just before their presentation and were only given the larger displacement immediately prior to production start-up. At a meeting of the Board of Management and directors in March 1935 to discuss the model range and vehicle disposition for the trade fairs in London and Paris in 1935 and Berlin in March 1936, the vehicles from the W 136 series for Berlin were described as having 1.6-litre engines.

This resulted in the fact that many of the number groups listed in the vehicle production records, for which chassis had already been reserved, were given a red stamp with the mark “1.6Ltr.” Then, following the rapidly modified displacement from 1,598 cubic centimetres to 1,697 cubic centimetres, the first series of the new vehicles were entered on these pages, without any correction being made to the existing stamp mark. In the case of the 170 H this applied to chassis numbers 118771 to 118780 and 136776 to 137775.

The increased displacement, which served above all to generate more torque, was achieved simply by modifying the manufacturing process to increase the bore from 72 millimetres to 73.5 millimetres, and by giving the crankshaft a 98-millimetre stroke instead of one of 100 millimetres. These modifications made no difference to manufacturing costs, particularly as they could be achieved using the same blanks.

The four-cylinder engine of the 170 H model developed an output of 28 kW at 3,400/min giving the car a top speed of 110 km/h. In addition to the body design, the significant factors here were the reduced vehicle weight resulting from the compact drive block and redundant propshaft, combined with reduced power transmission losses.

In contrast to the 170 V with its four-speed transmission, the vehicle had a three-speed transmission with selectable overdrive, just like the 130 model, although this was now designated a four-speed transmission. This made no difference to the engine speed range compared with the 170 V model, since the incremental tuning between transmission and axle ratios was such as to make engine speed ranges almost identical to those of the 170 V, despite it having a different transmission design.

The other technological concept of tubular backbone chassis with bifurcated rear frame to accommodate the rear engine was fundamentally identical to that of the 130 model. The underlying tendency to oversteer was present as before, although much reduced as a result of careful chassis tuning. The 170 H differed from the 170 V not only in terms of its avant-garde body; the rear-mounted engine also offered improved performance and reduced engine noise.

Polarising design

Compared with the 130 model, the 170 H had a much more pleasing body form, although in this case the Mercedes star was laid flat on the bonnet and not encircled. The vehicle’s appearance remained a topic for discussion when it was unveiled to the public at the IAMA.

In its reporting on the exhibition, for example, Motor und Sport wrote: “Has the general public finally grown accustomed to the shape of the rear-engine car or not? We, at any rate, can find nothing wrong with it. It is a modern car of which one can be proud and one which reveals to the world that its owner is a modern person. We liked the new rear engine (car) with its new four-cylinder 1.7 litre engine very much indeed.”

Even today one has to agree with this view. The 170 H is pleasing to look at, more so perhaps than the 130, thanks to its rounded, harmoniously integrated design, which even decades later remains attractive and convincing. If one places the 170 V and 170 H side by side, then it is the front-engine car that suddenly appears much more outdated to modern eyes than the astonishingly fresh-looking rear-engine model.

In this respect, the body designer Walter Häcker scored a major success, creating a design that can unquestionably stand shoulder to shoulder with any post-war car with a rear-mounted engine. Utterly convincing, too, are the unifying style elements around the windows, the B-pillars and the longitudinal beading, which create a link to other saloon bodies and enable the 170 H to identify itself as a member of the larger Mercedes-Benz family.

Although more compact on the outside, the interior of the 170 H was more spacious than the 170 V. Without an engine bonnet, the driver’s view was more reminiscent of that of many modern vehicles. Stowage space for luggage was improved compared with the 130, although this was not without compromises, since baggage had to be lifted over the back of the rear seats in order to place them in the trunk. But this was no different with the equivalent 170 V model – for this class of vehicle a trunk that was accessible from the outside was not introduced until after the Second World War.

Excellent suspension and noise comfort

The 170 H continues to impress even today’s drivers and passengers with its outstanding comfort levels for both suspension and noise and with its standard-fit heating system. On this last feature, the test report of the Allgemeine Automobil-Zeitung (AAZ) observed: “In addition to the car’s spaciousness, another very attractive aspect is the adjustable car heating system. Unfortunately, other than the 170 H, only few – mostly foreign – cars are equipped with this pleasing feature.”

The heating system was a by-product of the compressed-air cooling system borrowed from the 150 model. This forced air into a small water-cooled radiator by means of a “turbo blower” driven by the engine. Some of this air passed not only over the enclosed exhaust manifold but also over the silencer. This warmed air was then fed into the vehicle interior. It was possible both to regulate the heating system and to turn it on and off.

The 170 H was also faster than its popular brother with front-mounted engine. The response of the trade press was entirely enthusiastic. The magazine Motor und Sport filed an almost euphoric report from the IAMA: “Although the car is considerably more spacious than the

1.3-litre rear-engine car, its wheelbase is just 10 cm longer and it weighs just 30 kg more. The engine has an output of 38 hp, giving a power-to-weight ratio of 27.6 kg/hp. As a result, in addition to its unparalleled reputation for roadholding, Mercedes-Benz has now finally provided a dose of “pep” which will be welcomed by many.”

The following year a colleague writing in the AAZ made a similar observation: “The handling of the 170 H is supported by a very acceptable top speed and highly satisfactory acceleration. Top speed over the flying kilometre, recorded as an average of four runs, was 111.4 km/h, while a speed of 70.6 km/h was achieved over one kilometre with a standing start.”

Measures to produce a special-purpose version of the 170 H got under way even quicker, the model’s chassis being used by Karl Schlör at the Aerodynamic Research Institute Göttingen (AVA) to develop a streamlined body on behalf of the Reich Ministry of Transport. This was custom-built by the coachbuilding firm of Gebr. Ludewig in Essen. This prototype vehicle achieved a top speed of 146 km/h on the Frankfurt – Darmstadt autobahn, over an average of three timed runs. At the 1939 IAMA the car, which had the unusual feature of a centrally-positioned driver’s seat, was available for test drives by anyone interested from the motor industry.

The 170 H model was also given a facelift. From 1938 onwards it was equipped with dual-look bumpers, and the instrument panel additionally featured dials indicating water and oil temperature.

But the 170 H was never able to gain acceptance ahead of the 170 V. There were several reasons for this. For one thing, the 170 V was available in many more body variants, giving the customer a much wider choice. Another factor that hampered the success of the 170 H was its RM 600 higher price tag compared with the 170 V (RM 4,350 as opposed to RM 3,750). And that, even though the 170 H was 50 kg lighter than the 170 V. Just 1,507 examples of the 170 H were built between 1935 and 1939, whereas 67,579 front-engine 170 V vehicles came off the production line in total, including the Kübelwagen for military use.

For those who could afford one and had access to fuel rations, the 170 H model was a sought-after vehicle during the Second World War, because it was not one appropriated by the Wehrmacht. The army considered rear-engine cars to be unsuitable for their purposes – although this was before the Volkswagen-based Kübelwagen began its wartime career in Africa and Russia.

But this fact also helps explain why such a relatively large number of 170 H models survived the Second World War and why it was one of the few vehicles available for civilian use. But it was all to no avail. When more advanced concepts finally caught on, many of these very special Mercedes-Benz rear-engine vehicles ended up on the scrapheap – and very few survived.

Mercedes-Benz 170 H (W 28 series)

Cylinders: 4 (in-line)

Displacement: 1697 cm³

Output: 28 kW at 3400/min

Max. speed: 110 km/h

Production period: 1936 – 1939