Transporting goods over the San Bernardino: From mule tracks to modern-day horsepower

- The transportation of goods over the Alps has a very long history. It has been instrumental in shaping the development of Europe, always evolving hand in hand with economic expansion

- Opened in 1967, the San Bernardino tunnel is Switzerland’s second most important lifeline for commercial and private traffic after the Gotthard pass, guaranteeing that the Val Mesolcina remains firmly connected to the rest of the canton all year round. Continuing on via Bellinzona and Lugano, the San Bernardino pass road represents an important link to northern Italy and the major city of Milan.

- A Mercedes-Benz customer from Chur deployed his trucks to transport a total of 280,000 tonnes of cement to the construction sites

- The tunnel underwent comprehensive renovation between 1991 and 2006 at a total cost of around 150 million euros, bringing it into line with modern-day needs

- Grisons, the canton of the 150 valleys, is a typical mountain and highland region with the highest-lying permanently inhabited village in Europe and an average altitude of 2100 m above sea level. Streams and rivers flow from Grisons into three oceans

- The Daimler event “Transalp Trucking 2010” demonstrates the vast and ever more environmentally friendly improvement which have been achieved in the efficiency of trucks employed for transporting goods. The process of reducing fuel consumption and emissions while at the same time raising ergonomic and safety standards has been a focus of development work at Mercedes-Benz Trucks for over 50 years now

The swiftly expanding EU internal market accompanied by the collapse of the socialist economic system in eastern Europe has seen a more than three-fold increase in the volume of freight transported across the Alps in the past 40 years. This calls for a differentiated approach when considering the traffic situation throughout the entire swathe of the Alps from southern France to Vienna and from north to south. A distinction requires to be made between the so-called “indigenous traffic” resulting from the inhabitants of the alpine regions themselves, “tourist traffic” comprising holiday-makers and day-trippers, and the actual “transit traffic” covering all goods transport crossing the Alps and national borders.

According to investigations by Werner Bätzing, professor of cultural geography at the University of Erlangen and scientific advisor to the CIPRA international commission for the protection of the Alps, indigenous traffic makes up the overwhelming mass of traffic in the Alpine region (70 billion km p.a. for cars and 4-6 billion km p.a. for trucks). This barely conceivable accumulation of mileage results from daily trips between the alpine population’s homes and places of work, trips to central towns and journeys to business associates in and outside of the alpine region.

Truck traffic comprises inner-alpine transport and journeys to extra-alpine business associates (e.g. wood, milk, cattle transport or transportation of industrial goods produced in the Alps). Tourist traffic also clocks up a princely 15 to 25 billion km p.a. By comparison, the much maligned transit traffic involving trucks driving over the alpine passes, which often serves as a scapegoat for environmental and infrastructure problems, is decidedly modest in scale, at around 1.3 billion km p.a.

The economic and social dimensions of the topic of alpine transit traffic are important issues to Daimler AG, Stuttgart, as one of the world’s most successful manufacturers of automobiles whose vehicles from its Mercedes-Benz Cars, Daimler Trucks, Mercedes-Benz Vans and Daimler Buses divisions are to be found in all the above-mentioned traffic segments. The “Transalp Trucking 2010” event at the San Bernardino pass is also to be seen in this context.

This event featuring five historical Mercedes-Benz trucks spanning five decades and modern Actros long-haul trucks will demonstrate the positive changes which have taken place in the past decades with regard to the vehicles themselves and, in turn, in the area of alpine truck traffic in general. Together with the Julier pass, the San Bernardino pass over which the “Transalp Trucking 2010” convoy will proceed with five historical Mercedes-Benz trucks from five decades and modern Actros long-haul trucks is the most important north-west link in the Grisons canton.

It connects the Rheinwald valleys on the north side of the Alps with Misox (Val Mesolcina) on the south side. The distance between the respective starting points of the pass – Hinterrhein (1620 m above sea level), where the San Bernardino tunnel begins, and Mesocco (790 m above sea level) – is only four kilometres as the crow flies, but the road journey is 12 km long. The tunnel can also be seen as the border between the German- and Italian-speaking alpine regions.

The pass guarantees that the Italian-speaking southern valley region remains accessible to and from the rest of the Grisons canton throughout the year. Continuing on via Bellinzona and Lugano, the San Bernardino pass represents an important link for alpine transit traffic to the industrial regions of northern Italy and the major city of Milan. Today, around 165,000 trucks haul goods in the region of 3.5 million t over the pass every year.

A disadvantage for alpine transit traffic is the fact that it is restricted above all for technical reasons to a small number of passes which are also heavily frequented by tourist traffic (Gotthard, Brenner, Mont Blanc, etc.), making busy roads the order of the day. Conflicting interests are inevitable here, with options such as allowing batches of vehicles through in alternating directions, temporary traffic bans and other measures to control traffic flows providing only partial solutions.

Transit traffic in the Alps

Goods have been transported from north to south, from south to north, from east to west and from west to east in the course of trade between all European countries since time immemorial, with the Alps always representing an obstacle which had to be surmounted.

Some of the oldest stone tools found in the Alps bear eloquent witness to this ancient trade, demonstrating how people have always attempted to overcome the natural imposing barrier that the mountains posed to their endeavours. The incorporation of the Alps into the Roman empire with its diversified economy and the Romans’ introduction of wine growing and the sweet chestnut in the southern valleys led to more intensive agricultural use of the region, which in turn gave rise to a denser population and an inevitable increase in traffic.

The first boom in transit traffic arrived together with the Romans, whose cis-alpina (‘beyond the Alps’) legions required weapons and provisions – as documented by Roman scribes. At the same time, trades, craftsmen and others were also drawn to the region.

Rome conquered large areas of the Alps around the time of the birth of Jesus, primarily for strategic and military regions. The Romans adopted the same procedure here as elsewhere, deporting insurgent tribes and replacing them with new subjects. The cultural and economic blows dealt by this policy were offset by notable achievements by the Roman rulers. Road building is one of Rome’s great contributions to civilisation. In the east of Switzerland at least – today’s cantons of Grisons and St. Gallen – their road network was largely limited to the valleys, however, as the Romans generally took a pragmatic approach to road building, avoiding the wild mountains wherever possible.

According to Swiss historian Raphael Reinhard, the Romans “did not open any new alpine passes at all, instead merely improving the old ones used for local transport.” The first alpine road network, as seen from west to east and often based on improved existing tracks, consisted of the following pass roads which still exist today: Colle di Tenda (Italy/France); Little St. Bernhard Pass, Graian Alps (France/Italy); Montgenèvre Pass, Cottian Alps (France), which was known in Roman times as the Via Domitia and served as an important link between the Rhone Valley and the Po Plain; Septimer Pass, Grisons, which leads directly into the Val Bregaglia and is now the reserve of mountain-bikers and hikers; Maloja and Julier Pass, Grisons; Reschen Pass, Southern Tyrol; Brenner Pass, Austria/Italy; Radstätter Tauern, Austria.

All these routes can be traced back to the Romans’ strategic needs. They existed as mule tracks and paths even before they became the subject of Roman expansion interests, however.

Two- and four-wheeled carriages were able to travel on the Roman roads. In some instances channels were actually hewn into the rock in order to prevent transport carriages from leaving the track and plunging over rocky inclines, which was a particular danger at night. Information on distances and milestones were also installed, and numerous caravan routes were produced for mule-drawn carriages. Many of these roads fell into disrepair after the fall of the Roman Empire. Nevertheless, Roman land surveying (“limitation”) and road-building experience left its mark on trans-alpine traffic as a whole, as well as bequeathing useful routes for later generations which remain visible to the present day as so-called Roman roads and play their part in defining the landscape of numerous regions throughout Europe.

Trade in Europe

After the Roman age, trade retained an important role among the participating peoples in the Middle Ages, too. By the 10th century there was an array of trade routes leading from northern Europe – England, France and Germany – to Italy. Many merchants who did not enjoy exemption from tolls when travelling in a north-south direction entered Italy via the Pass Mont Cenis in the Graian Alps, which leads into Italy from France and was already in use back in Roman times.

Trade flourished as a result of a growing number of new settlements which were built at this time and the rapid spread of handicraft products intended for export. Against this background, the road network was expanded and improved. Walling, fencing and safety on the roads also improved considerably. This enabled roads to be built over the Alps linking the most important centres of trade and industry in northern and central Italy with those of north-western Europe – from the Ile de France through Champagne and Flanders to northern Germany.

By the end of the 13th century the trade route via St. Gotthard and the Little St. Bernhard pass was already well used by merchants and their transporters. These routes linked Milan, Venice and Genoa with Gent (with stretches leading along the Rhine from present-day Basel to the region past Karlsruhe), Troyes and Paris. The roads then continued on to London or Hamburg. Important trade products included salt, textiles, cereals and wine on the route from south to north. Wool, hides and honey were key items of merchandise traded in the opposite direction.

For many centuries, a knowledge of routes, local circumstances and weather conditions was crucial to the trading and transportation of goods of the most diverse nature. It was above all the Walser, an Alemannic people, who rose to prominence in this new, fast-growing and much in-demand field of business. Geographic terms in the alpine area such as the Great Walser Valley and the Little Walser Valley remind us of this people up to the present day.

According to Werner Bätzing, in the course of the so-called Walser Colonisation, which was triggered by a strong population increase, they settled first and foremost at the high-lying ends of valleys, where space for permanent settlements was still available. Other regions in which they settled include large areas of the Grisons canton (also the region of the San Bernardino pass), Italian alpine valleys to the south of the Monte Rosa massif, Vorarlberg, Tyrol and the Allgäu region.

These were all regions in which the flows of goods from north to south had to negotiate the mountains. For the Walser people, the rise of the new occupation of “Säumer” or “pack animal transporter” meant that the women were left to attend to whatever farming was possible in these climes while the men earned their money transporting goods over the passes, thereby indirectly fostering contacts with the markets in the lowlands. This increasingly gave rise to local “Säumer” cooperatives to deal with the business of transporting goods in the Alps.

The business of handling and transporting goods became an important occupation for the people living along the trade routes long before the arrival of the railway and goods vehicles. The transportation of goods was already well organised in the Middle Ages. The organisational set-up back then divided the transport routes into stretches between larger towns which possessed staple rights. These rights required the traders to deposit their goods at the bale house in these towns and to change carriage.

This meant that the carters only ever covered relatively short routes, which they also knew well. This avoided overstraining the draught animals and assured the merchants that their goods would be transported in reliable fashion. This system ensured that business remained in the hands of the local carriers and no-one was able to take control of the entire route. A further important economic aspect of transport business at this time was the fact that inn proprietors, carters, packers, craftsmen and carriers at all key points along the trade routes were able to earn good money all year round from the flourishing transport activities.

Trams and railways herald a new age

Europe’s proto-industrialisation (commercial production of goods in distributed workshops and manufactories) had a marked impact in Switzerland. All over the land, the inhabitants of rural areas began manufacturing products for export on a decentralised basis. Traders brought the necessary raw materials from which entire families made products such as clothes. The traders then purchased the finished goods, giving rise to an early form of industrialisation. During this era of expansion, which ensued first and foremost in the 18th and 19th centuries (after the Congress of Vienna), roads were built and improved everywhere – not least of all in order to transport the growing flows of goods more efficiently and more quickly.

Dr. Jürg Simonett, director of the Rätisches Museum in Chur, describes the conditions which prevailed in the transport trade in the Grisons canton at the time thus: “The growing volume of traffic gave rise to transport associations or, more precisely, carters’ guilds. The transit goods were generally carried by pack horses. This locally oriented system of freight transportation was to be found throughout the entire alpine region. The carters held a monopoly in their respective areas, which they defended vigorously against any challenges.

According to Simonett, the carter-based organisation certainly entailed benefits for the carriers. “In view of the poor condition of the mule tracks and the extreme alpine weather conditions, it appeared extremely important for the goods to be transported by people who knew the local terrain and were able to evade impending hazards in good time,” he writes.

Chur carriers’ guild provides financial backing

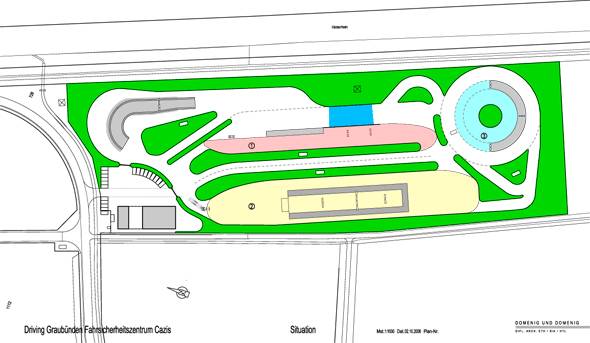

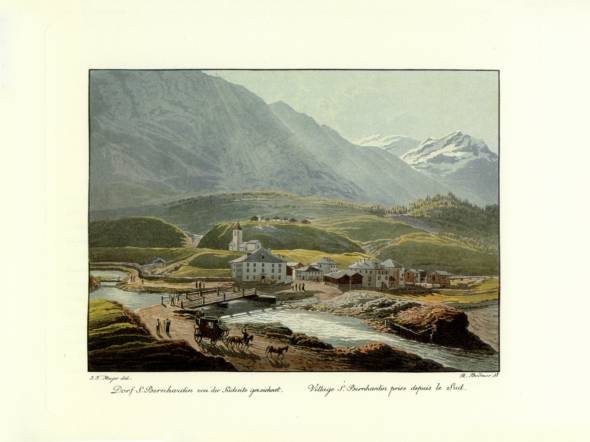

“Until the road construction operations which took place between 1818 and 1823, there was no such thing as through traffic on either the Splügen or the San Bernardino pass,” notes Simonett. In 1817 the Grisons government commissioned the road builder and Ticino state councillor Giulio Pocobelli from Melide to cost and draft a project for the 120 km long road from the Rhine valley near Chur via the San Bernardino pass to Ticino’s canton border just before Bellinzona in the Valle Mesolcina.

The Chur carriers’ guild played a prominent role in financing the project, with the aim of seeing as many as possible of its ideas on a strong and well organised transport system turned into reality. The final costs of building the road via San Bernardino and Splügen in the Grisons territory totalled almost 2 million Swiss francs, 724,000 francs of which were provided by the Chur carriers’ guild. The Bernardino road, which was six metres wide along its entire length, was passable in 1821, and the new stretch of road from Splügen am Hinterrhein up to the elevation of the pass and the Italian border was opened to traffic in 1822. The San Bernardino pass road was finally completed in 1823. Traffic over the pass reached its pinnacle in the mid-1950s. The journey from Chur to Milan now took just under two days.

1867 signalled the beginning of the railways’ rise to power in the alpine region, leading to an abrupt decline in road traffic. Until 1914, the entire volume of transit traffic was concentrated on just six lines – Fréjus (France), Lötschberg-Simplon (Switzerland), Gotthard (Switzerland), Brenner (Southern Tyrol), Tauern (Austria) and Pyhrn (Austria). Many alpine valleys were sidelined as a result, as there was little railway coverage for the major east-west routes, which were served for the most part by narrow-gauge lines.

One of these, the Rhätische Bahn in Grisons, was one of the most important such narrow-gauge railways in the entire alpine region. Meanwhile, the major cross-border railway network in the Alps clearly reflects the extra-alpine interests that were at work here. The alpine railways over the Brenner pass (1867) and through Mont Cenis (1872) diminished the share of alpine transit traffic using the San Bernardino pass substantially. Finally, the opening of the Gotthard railway (1882) virtually brought traffic over the Grisons passes to a standstill.

Automobiles and the fine art of road building

The first major expansion of the alpine road network also represented a pinnacle of the fine art of road building. Joseph Baumgartner, a road builder who made a name for himself as an engineer in the early 19th century, was inspired by the road through the Via Mala between Thusis and Zillis to wax lyrical on the “victory of art over the most rugged nature”. Today’s motorway passes at a safe distance to the left of this awe-inspiring gorge with its rock faces rising to a height of 500 metres, but anyone making the short detour to the Via Mala to take in this scenery is sure to be overwhelmed by the sight of such a colossal spectacle of the brute force of nature set in stone.

One cannot but admire the road builders’ courage, vision and achievements. With fascinating constructions in the guise of bridges, tunnels, galleries and avalanche barriers they created the essential road infrastructure for the unremitting, all-year-round, sometimes crawling, sometimes frightening beast that is alpine traffic. In this context, references to the “fine art of road building” are to be understood as alluding on the one hand to the architectural merits of the roads and on the other to the engineering feats required to wrest this terrain from nature and turn it into something akin to a man-made monument to industry and economic aspirations.

It was motor traffic which enabled even the most remote valleys to participate in the development of the alpine economy as a whole. The construction of the San Bernardino road between Grisons and Ticino also resulted in a passable road over the Gotthard, for example. In numerous mountain regions, tourism soon began to play a significant role in the development of the road network. The art of road building, as practiced above all in Grisons by world famous architects such as Peter Zumthor or Jürg Conzett, brought northern and southern Europe noticeably closer together. As such, the Alps and the traffic passing through the alpine region have undoubtedly played an important role in the integration of Europe.

This development was not always regarded as a welcome sign of progress. The “Handbuch der Bündner Geschichte” (“Manual of Grisons History”) contains a section headed “The battle over the automobile”. “The first cars appeared on the streets in Grisons in the final years of the 19th century”, the manual relates. “The new vehicles caused a major stir and soon gave rise to complaints. In view of the danger to postal services and other traffic, the government thus imposed a complete ban on cars on the streets of Grisons without further ado in August 1900. It issued a number of special exemptions, in particular for freight-carrying vehicles.

In 1907 an ordinance was drawn up with the aim of permitting car traffic on through roads. In the subsequent plebiscite the bill suffered a massive defeat, however. It took no less than ten hotly contested ballots between 1907 and 1925 before Grisons finally accepted the principle of motorised transport – as the final canton to do so in Switzerland and very much later than the adjoining countries. Even after cars were partially approved by a narrow majority on 25 June 1925, not all roads were opened immediately.

In particular, the freight-carrying vehicles were forbidden from using the routes which were served by the Rhätische Bahn railways.” Right up until 1931, it was only permitted to cover half of the distances on mountain routes with motorised vehicles, in order to salvage part of the horse and carriage owners’ livelihoods. Only after 1931, following a total of 11 plebiscites (!), was commercial traffic permitted without restrictions.

Potholes and other difficulties

It was thus 1931 before Hans Fischer, taxi and haulage operator from Chur, was able to obtain the first licence for a commercial vehicle in the canton. Over 30 years later his son, Hans Fischer, senior director of the eponymous transport and excavator business in Chur, was deploying his trucks in daily cement transport operations in connection with the improvement of the San Bernardino pass road and the construction of the San Bernardino tunnel.

The cement came from the cement works in Untervaz near Chur, from where it was transported by the Rhätische Bahn railways to Thusis. Over the seven-year construction period his trucks hauled 280,000 tonnes of cement for the construction of the 12 smaller tunnels along the 38 kilometre route between Thusis and Hinterrhein and to the construction site for the 6.6 km long San Bernardino tunnel. “We were on the road every day, with up to seven bulk transporters running from the cement works in Untervaz am Rhein to Hinterrhein. One trip took two and a half to three hours”, the transport operator recalls. He still has a clear memory of the major problems encountered on the stretch from Splügen to Hinterrhein.

The road was poor, with just a gravel surface and one pothole after another. Hans Fischer, a venerable transport pioneer in the Grisons canton and regional president of the Swiss commercial transport association, ASTAG, remembers: “It was an arduous drive on this final stretch of the run, which only permitted a top speed of 25 km/h. Wheel suspension damage was the order of the day. When we received the order we were told that 45 t of cement would be required every day.

In order to cope with these transport needs we purchased the first semitrailer tractor in the entire canton, a Mercedes-Benz 338 rated at 172 hp, with a 10-speed dual gear ratio and a payload of 12 t. In the course of construction it emerged that the difficult geological conditions called for up to 120 t of cement a day. As a result we had to deploy up to seven trucks a day, including our three brand new, state-of-the-art Mercedes-Benz 1920 cab-behind-engine vehicles rated at 200 hp, with a payload of 9 t and the first direct injection diesel engine – the OM 302.”

Comprehensive renovation after 25 years

In 1967 the 6.6 km long San Bernardino tunnel was opened as part of national road 13 between the villages of Hinterrhein in the Rheinwald and San Bernardino at the beginning of the Val Mesolcina on the southern side of the Alps. As part of the Swiss traffic concept the tunnel, which is open and passable all year round, links eastern Switzerland and the Lake Constance region with Ticino and ultimately the industrial region around Milan in northern Italy.

The pass road at an altitude of 2065 m above sea level is still only open in the summer and is not suitable for commercial traffic. Today, it is used mainly as a scenic alternative to the tunnel, which is particularly busy in the summer. After the Gotthard tunnel, the San Bernardino tunnel is the second most important alpine crossing for commercial and private traffic in the Swiss transport system, including cross-border links to Germany and Vorarlberg (Austria). Around 25 years after its opening, the tunnel had to undergo comprehensive renovation and structural alterations without interrupting the flow of traffic between 1991 and 2006, as today’s traffic volumes were unforeseeable when the initial plans for the tunnel were drawn up, in addition to which the safety concept also required extensive modernisation. The costs of this complete renovation totalled around 150 million euros.

Grisons as a transit region

The Grisons canton has formed part of Switzerland since 1803. The capital is Chur, the oldest town in Switzerland, with a population of around 35,000. It is the only tri-lingual canton in Switzerland. Around 70 percent of the population speak German and 15 percent Rhaeto-Romanic, which in turn breaks down into various linguistic sub-regions and idioms. And finally, around 10 percent of the population speak Italian, concentrated primarily in the southern alpine valleys of Val Mesolcina, Bergell and to the south of the Bernina mountain range in the Valle di Poschiavo.

The canton of 150 valleys is a typical mountain and highland region with an average altitude of 2100 m above sea level and the highest permanently inhabited community in Europe – the village of Avers-Juf (2126 m above sea level) in the high-lying valley of Avers (motorway exit: San Bernardino pass road), a starting point for magnificent hikes to the Maloja and Bergell regions. The highest mountain in the canton is Piz Bernina, at 4049 m. The Grisons mountain farmers are a special feature of the economy, along with the tourist industry founded on the world famous spas of St. Moritz, Davos and Klosters. Over half of all the mountain farms are run along organic lines.

Mountain farmers tend the land throughout the entire sweep of the Alps, producing grapes and chestnuts in the south, along with dairy products and arable crops. Vineyards extend into Chur’s Rhine valley area. Streams, rivers and over 600 lakes define the special allure of the Grisons mountain landscape. Waterfalls and gorges – such as the Via Mala or the Rhine Gorge – create unique natural scenery. Various bodies flow into three seas from the Grisons: the Rhine flows into the North Sea 1320 kilometres downstream of its source in Grisons, the Inn flows into the Danube and on into the Black Sea and the rivers from the Val Mesolcina, Bergell, Puschlav and the Val Müstair flow into the Adriatic.

Transalp Trucking 2010

The Daimler event “Transalp Trucking 2010” demonstrates the vast and ever more environmentally friendly improvements which have been achieved in the efficiency of trucks employed for transporting goods. The process of reducing fuel consumption and emissions while at the same time raising ergonomic and safety standards has been a focus of development work at Mercedes-Benz Trucks for over 50 years now. Ever since the automobile was invented by Carl Benz and Gottlieb Daimler, the company has been setting standards as a technology leader. Efforts to attain noticeable reductions in fuel consumption, CO2 emissions and exhaust emissions continue apace.

The “Clean Drive Technologies” from Daimler make a crucial difference here, with efficient and clean drive systems and alternative fuels for all classes of vehicle. Ongoing development efforts have seen diesel engines from Daimler evolve into high-tech units which will remain the backbone of the commercial vehicles industry for many years to come. Their potential is manifested by ever lower emissions and ever higher energy efficiency. Fuel consumption has been cut dramatically once again, for example, by 2000 litres a year for a long-haul truck.

Emissions of particles and nitrogen oxides have also fallen on average by well over 90 per cent since 1990. In view of this highly positive course of development for the environment and human society, Grisons provides an apt setting for the “Transalp Trucking 2010” driving event, with demonstration drives over the San Bernardino featuring trucks from five decades. The results of efforts to reduce the fuel consumption of trucks bear up to scrutiny: compared to the 6 litres of fuel per tonne of payload which were required by the trucks of the past, a modern-day Mercedes-Benz Actros from 2010 gets by on just 1.8 litres.