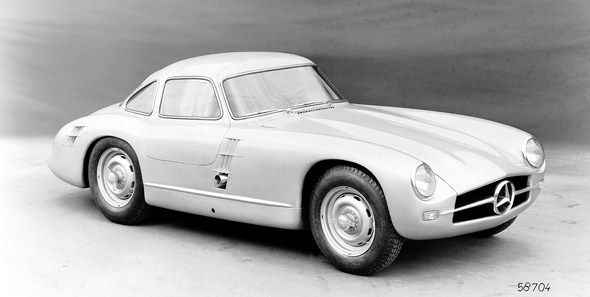

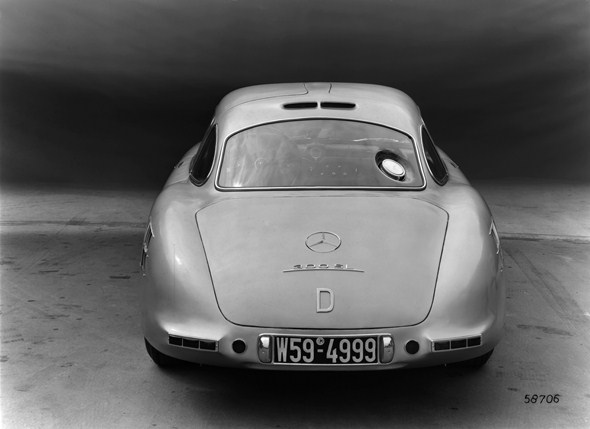

The Mercedes-Benz 300 SL (W 194 series) with chassis number 11

Mercedes-Benz Classic

- Developed for the 1953 racing season, but did not race after all

- Petrol direct injection and transmission in transaxle position

- An intermediate model on the way to the 300 SL (W 198 series) production sports car launched in 1954

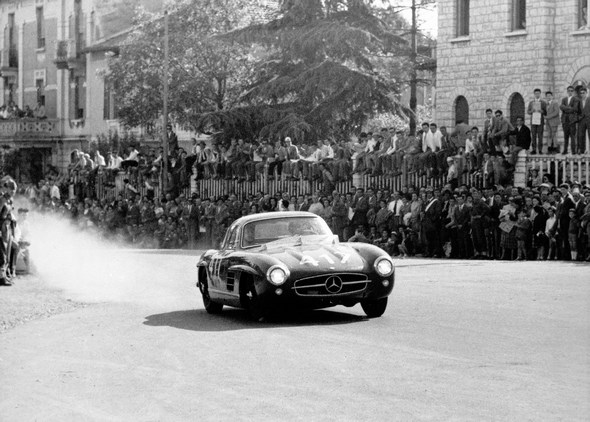

Stuttgart – The 300 SL with chassis number 0011/52 was a very special car in the history of the SL. Developed for the 1953 racing season, it did not see action because Mercedes-Benz decided to return to Formula 1 racing from 1954 on.

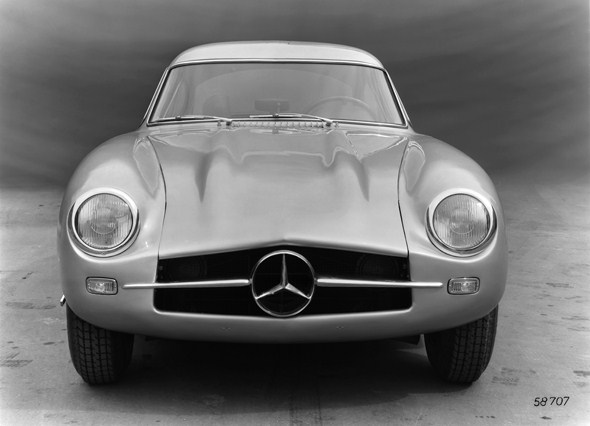

This made the “carpenter’s plane” – as the vehicle was affectionately dubbed by the research engineers because of its characteristic front section – an intermediate model on the way to the 300 SL (W 198 I series) production sports car that was launched in 1954.

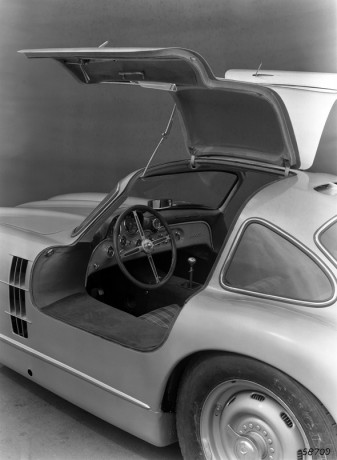

The unique specimen, a continuous possession of the company since 1952 and today in the care of Mercedes-Benz Classic, featured an engine with petrol direct injection, while its transmission was located in a transaxle position.

Actually this intermediate model, in particular, fully deserves the designation “Uhlenhaut-Coupé”, for it was engineer Rudolf Uhlenhaut who designed the vehicle that was then built precisely according to his concepts and ideas. This is only entirely true of this model.

The “carpenter’s plane” is also the only SL of the whole SL series that can claim to be a prototype, a vehicle intended as a preliminary stage for others to follow.

Unlike the previous racing cars with which it shared the designation W 194 (chassis numbers 1 to 10), Number 11 remained unique.

A singular specimen that – in terms of its engine – influenced the 300 SL (W 198 I) production sports car, but whose chassis constituted a preliminary stage to the racing and sports cars of the W 196 series that were built from 1953 onwards and participated exceptionally successfully in international racing in 1954.

After the extremely successful 1952 season, the decision was initially taken to resume participation in racing in 1953. With this scenario in mind, Uhlenhaut put the 300 SL (W 194 series) on the test rig and, after evaluating it, came to the conclusion that it would no longer be competitive in the following season.

He saw potential for improvement in the engine output, the road grip of the rear wheels, the durability of the tyres, the brake performance, and the reduction of driving resistance.

At the same time he formulated an ambitious concept that was to lead to a complete re-design of the W 194.

Comprehensive performance optimisation

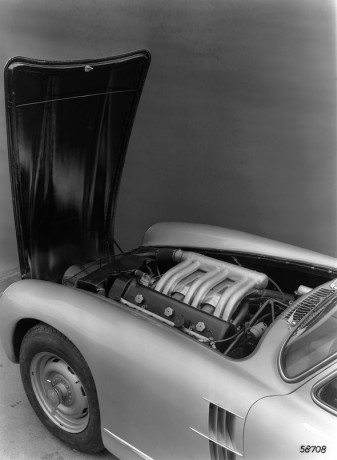

Uhlenhaut began with the engine output enhancement and rightly chose petrol direct injection, a measure which together with other peripheral measures led to an output of 214 hp (157 kW) at that time.

At the same time he advised against seeking the solution to all problems exclusively in increasing the output, writing, “In my opinion it would be wrong to expect a significant increase in the average speeds as a result of an increase in output and maximum torque.

The following examples support this opinion: at the Nürburgring neither Kling, Lang nor I were faster driving a compressor SL, which was working perfectly, than we were when driving a normal SL”.

The second fact Uhlenhaut mentioned was the reduction of power requirements: this included drag reduction, which was difficult to achieve because the already optimised body shape of the W 194 could hardly be further improved upon.

Uhlenhaut required a reduction of the frontal area, something that could only be brought about by narrowing the track width; this in turn made a new solution for the rear axle necessary: “However here […] a modification in detail of the rear axle system is needed,” wrote Uhlenhaut.

According to his calculations, reducing the frontal area would lead to 2.2 hp (1.6 kW) lower power requirements at 150 km/h, and a reduction of 10.5 hp (7.7 kW) at 250 km/h.

He determined even greater power requirement savings by changing the coolant air circulation. The conventional circulation with air vents under the vehicle before the rear axle increased the cd value by 20 per cent.

If, however, the cooling air was dissipated in the low-pressure area behind the front wheels, the cd value only increased by 5 per cent.

This measure led to a reduction of 6 hp (4.4 kW) at 150 km/h and of 17.4 hp (12.8 kW) at 250 km/h. Implementing both of the above measures together brought about a reduction in power requirements of 28 hp (21 kW) at 250 km/h – a powerful statement.

Another measure consisted in reducing weight. Here Uhlenhaut calculated that the use of Elektron metal (a magnesium alloy) instead of Duralumin® (a high-strength aluminium alloy) in combination with the smaller surface would result in weight savings of 30 kilograms.

A further 30-kilogram reduction could to be achieved by using an aluminium crankcase. And diverse other modifications, for instance, a lighter transmission housing, lighter shock absorbers, lighter connecting rods and flywheel, were to lead to weight savings totalling 96 kilograms, according to his reckoning.

26 kilograms would have to be deducted from this total, due to shifting the transmission to the rear axle, the fuel injection system and the use of 16-inch wheels.

Weight and chassis improved

Uhlenhaut went to great pains to ensure improved rear-axle roadholding. The peculiar characteristic of the dual-pivot swing axle, which due to the high instant centre of motion tends to relieve the load on the inside wheel in narrow curves, led to an even stronger tendency to lift the wheel (and consequently to wheel spin) in the case of a narrower track width.

This prevented significantly better lap times and rendered the axle design useless, as tests with the W 194 and compressor engine demonstrated.

Uhlenhaut’s conclusion: “I believe that without lowering the pivot centre of the swing axle and without a longitudinal support of the drive wheels the 300 SL will not be able to achieve a significant increase in performance on winding roads even if the engine output is far greater than at present.”

In order to achieve an even weight distribution for the rear axle, even with an empty fuel tank, he suggested reducing the wheelbase from 2400 to 2300 millimetres.

In spite of the 16-inch wheels, and thus larger drum brakes, he also suggested testing disc brakes, which he credited with greater fade resistance.

Except for one measure, namely the use of disc brakes, all of these were implemented in the vehicle with the precise chassis number W 194/010000011/53.

Even an engine with an aluminium crankcase was used at times – as new historical evidence reveals: the test engines M 198/81 and 198/82, used in test drives in Hockenheim and at the Solitude racetrack in 1953 and 1954.

The “carpenter’s plane” was by no means a case for prototype

hunters, so widespread today. Quite the contrary, the vehicle was officially a part of the company fleet and was also intensely used for driver training in Hockenheim, Monza and Solitude in 1953.

It was even portrayed on the cover of the November 1953 issue of “ADAC Motorwelt”, the magazine of the German Automobile Club, achieving a certain measure of fame.

The measures taken for weight reduction were significant. A comparison between the W 194/8 (1095 kilograms) and the W 194/11 (1009.5 kilograms), both under equal conditions with a full 150-litre fuel tank and both with cast iron engine blocks, shows their success.

With a cast aluminium engine instead of cast steel the weight could have been reduced even further – by 44 kilos, as contemporary tests show.

The plans for the modified bodywork of the W 194/11 came from coachwork designer Walter Gragert, who had formerly worked for the renowned coachbuilder company Gläser in Dresden.

The performance of the W 194/11 was markedly superior to those of the other W 194 series cars of 1952. In Monza, Juan Manuel Fangio clocked a lap time of 2 minutes 15 seconds on 30 September and 1 October 1953 with the W 194/8; while he clocked a time of 2 minutes 7.5 seconds with the W 194/11.

At the wheel of the W 194/8 Uhlenhaut achieved a best time of 5 minutes and 11.5 seconds at the Solitude racetrack in October 1953, compared with 5 minutes and 3 seconds piloting the W 194/11.

And yet in spite of all the progress made, contrary to the original plan, the W 194/11 was not to be built. Two reasons in particular spelled the end for this promising prototype: the decision at Mercedes-Benz to resume racing in Formula 1 from 1954 and, also starting in 1954, to participate in the sports car world championship with a racer developed on the basis of a Formula 1 racing car, but with even greater power output than the W 194/11.

Here the better was indeed enemy of the good – nevertheless, the intermediate model earned a well-deserved place in the company’s chronicle.