- 300 SL sports car (W 194) successful in all famous races

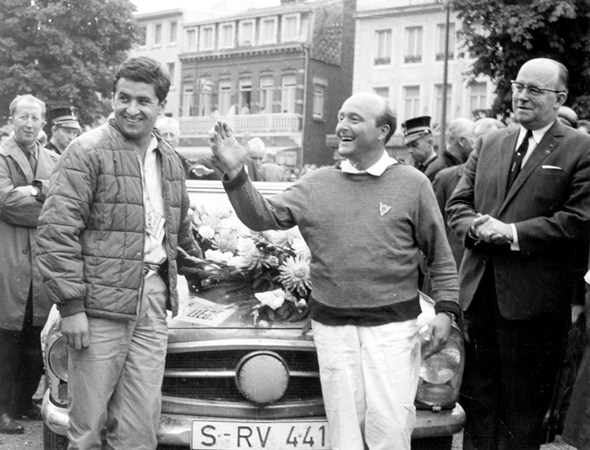

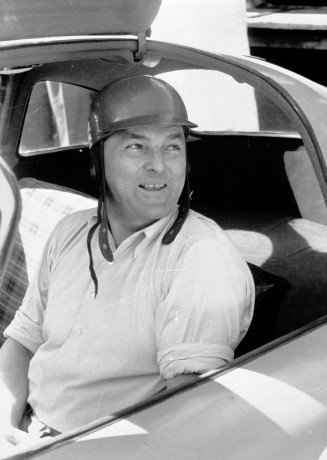

- Outstanding rally results for Eugen Böhringer in the “Pagoda” as well

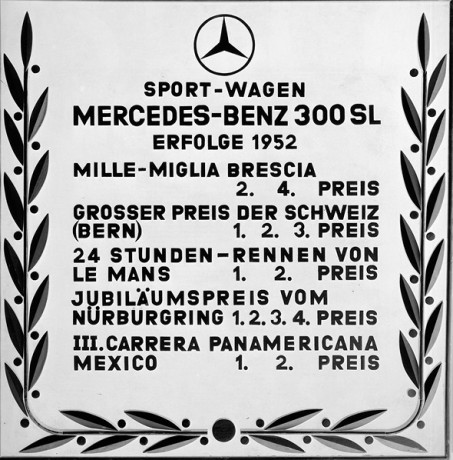

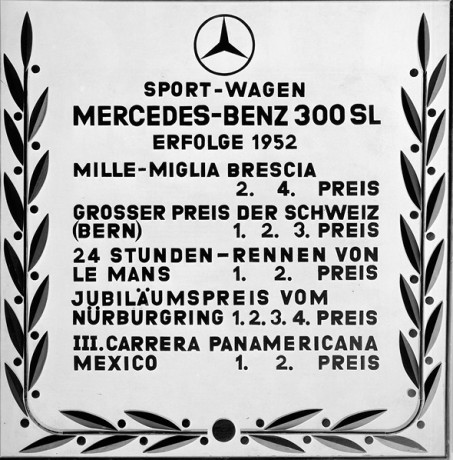

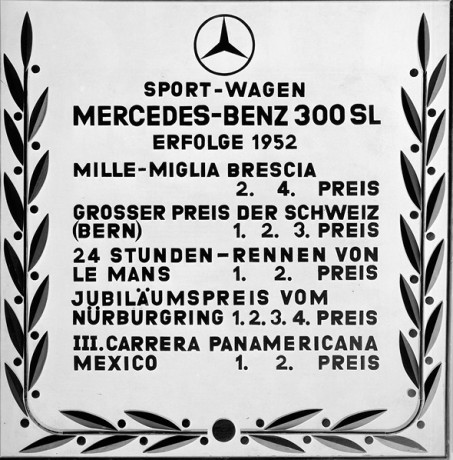

Stuttgart – From the very beginning, the Mercedes-Benz 300 SL (W 194) was designed exclusively for racing. At its presentation on 12 March 1952 it caused a considerable stir with its uncompromising, streamlined racing design. Its successes during the entire 1952 season were tremendous – it won all major sports car events in international motor sports.

It also passed on its sporting genes to following generations in the SL series. But it all began with the 1952 racing season.

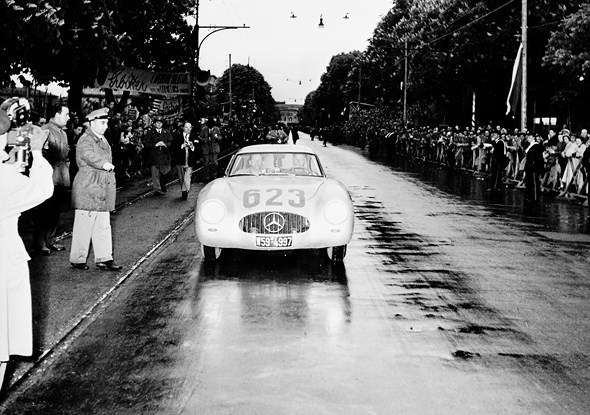

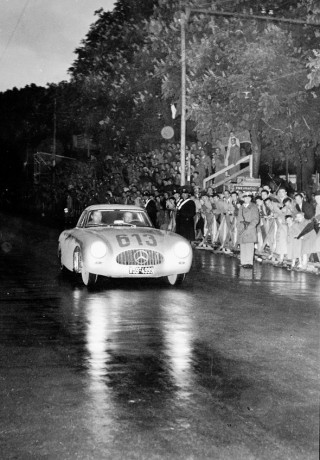

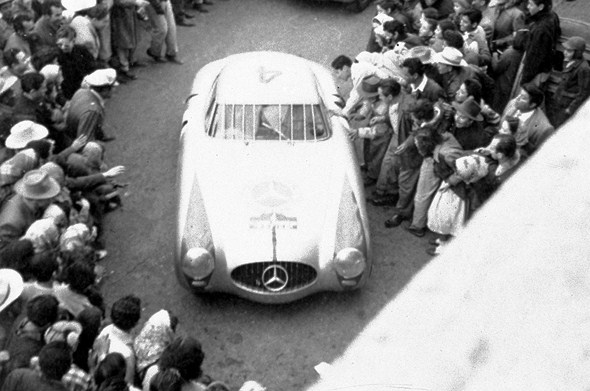

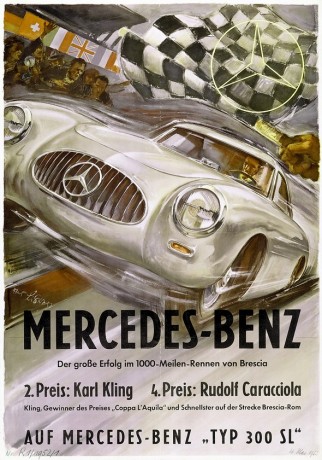

Mille Miglia, 4 May 1952

Its first racing appearance in the legendary Mille Miglia on 4 May 1952 was awaited with great suspense. The only non-Italian to win the race previously was Rudolf Caracciola with co-driver Wilhelm Sebastian in their legendary Mercedes-Benz SSKL in 1931 (discounting the Mille Miglia of 1940, held on a shortened course and won by Huschke von Hanstein in a streamlined coupé based on the BMW 328).

Of the three Mercedes-Benz 300 SL (W 194) entered in the race, Rudolf Caracciola/Paul Kurrle were the first pair to start at 6.13 a.m. with chassis number 0005 and No. 613 – the starting time is always the competitor’s number. They were followed at 6.23 a.m. by the team Karl Kling/Hans Klenk with chassis number 0004 and three minutes later, at 6.26 a.m., by Hermann Lang/Erwin Grupp in the car with chassis number 0003.

But the exciting battle between Mercedes-Benz and Ferrari had already begun earlier. One of their fiercest rivals, Giovanni Bracco, had started at 5.33 a.m. Hermann Lang was forced to retire from the race early on in the Po valley as shortly before Ferrara he took a left-hand bend too fast and damaged his rear axle beyond repair on a kilometre stone.

At the traditional turning point of the course, Rome, Karl Kling was in the lead – he had taken it at Aquila, but in Bologna Bracco had once again forged ahead with a 25-second lead over Kling. By the time he reached the finishing line in Brescia, Bracco had been able to increase his lead to 4 minutes and 23 seconds, and Kling had to be happy with second place.

What might look like a defeat at first glance was really a success for a new design that had no forerunner in the history of the company, Mercedes-Benz had been able to take 2nd and 4th place at first go. From Rome to Brescia, Rudolf Caracciola had managed to work his way forward from 9th to 4th place. And Mercedes-Benz was able to score yet another success with its brand new vehicle: among the first six places with five different brands, Mercedes-Benz was the only brand to be placed twice.

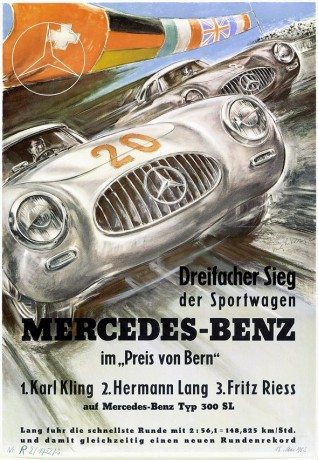

Bern Grand Prix, 18 May 1952

In addition to the Swiss Grand Prix, the Bern Grand Prix was held at Bremgarten Ring just outside Swiss federal capital on 18 May 1952. It was exclusively for sports cars with more than 1.5-litres and appeared to be tailor-made for the new Mercedes-Benz racing sports car.

The brand came to the Swiss capital with four 300 SL (W 194) and an illustrious group of drivers. Rudolf Caracciola, Hermann Lang, Karl Kling and the up-and-coming young driver Fritz Riess each took the wheel of one of the newcomers, so eagerly awaited by the spectators.

They would not be disappointed. But the race had a number of surprises in store. The first was the best time of Swiss sports car champion Willy Daetwyler in pre-race practice. He was driving the most powerful car in the field, a 4.1-litre Ferrari 340 America. He started from the first row next to Kling and Lang. Caracciola and Reginald Parnell in an Aston Martin DB2 stood in the second row.

The second surprise – and a disappointment for many spectators – was that Daetwyler dropped out right at the start when his car simply rolled to a stop after a few metres with no power whatsoever because of a defective driveshaft. Caracciola got off to a lightning start and immediately took the lead, as in the old days, but had to give it up to his old rival Lang on the second lap.

What then followed was an exciting chase by Kling to catch up with Lang. In a tenacious battle for the lead, Kling finally overtook his teammate. This contest – fought without instructions from the team – made the race very exciting and compensated the spectators for the 1-2-3 Mercedes-Benz procession at the finish.

The third surprise was when Caracciola was forced to retire after a head-on collision with a tree when his brakes failed. This accident not only meant the race was over for the ex-champion, it also spelled the end of his racing career. Kling, Lang and Riess finished in the top three places. Two points remain to be noted: Fritz Riess in car 0006 drove the first 300 SL with the large gullwing door.

And the cars were all painted different colours, chosen by Chief Engineer and Board of Management member Fritz Nallinger so that they could be more easily distinguished from one another in the race.

Lang’s car 0003 (No. 20) was painted in the DB colour 120 (blue), Kling’s 0004 (No. 18) in DB colour 229 (green), Caracciola’s 0005 (No. 16) in DB colour 516 (red), and Riess’s car 0006 (No. 22) in its usual silver.

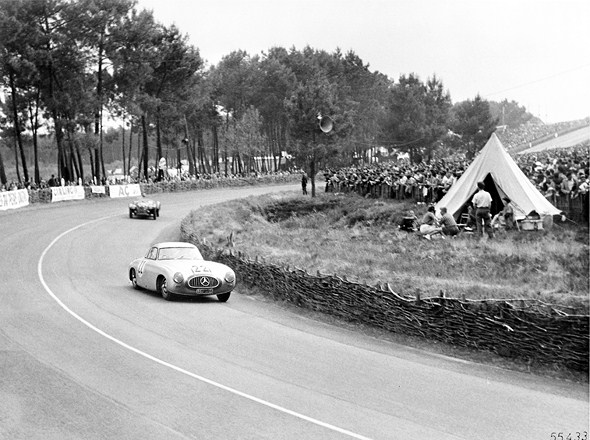

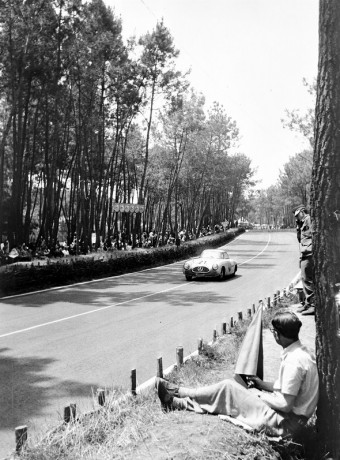

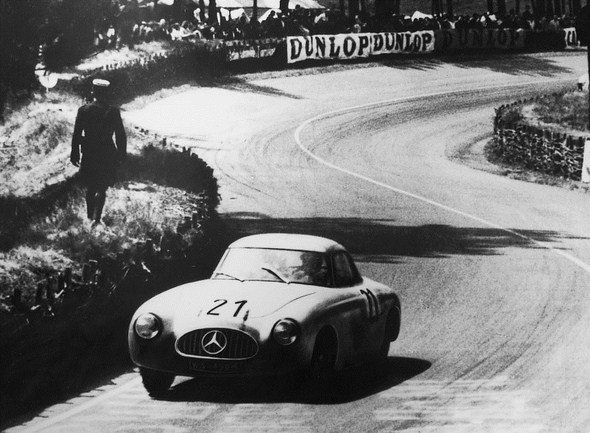

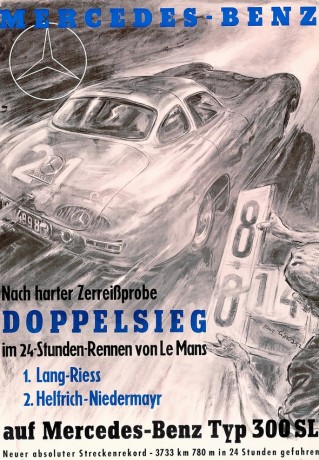

24 Hours of Le Mans, 14/15 June 1952

Mercedes-Benz had won almost all the important races at least once during the previous decades. Only one feather was still missing in their cap: the 24-hour race of Le Mans – this was a race for which the 300 SL (W 194) was predestined.

And so the preparations for participating in this classic long-distance race started a year before the race. In 1951, the Untertürkheim racing specialists swarmed out to familiarise themselves with the peculiarities of this race. In July, Prince Wilhelm von Urach and Alfred Neubauer sent their very detailed reports on their visit to CEO Wilhelm Haspel and Chief Engineer Fritz Nallinger.

The international rules for sports cars were sent to Walter Häcker from the Sindelfingen Design Engineering department and his colleague, Senior Engineer Roller from the head engineering office in Untertürkheim. Ludwig Kraus played observer at the Swiss Grand Prix in early June and discovered there that the Ferrari and Alfa Romeo racing cars had tubular frames of various designs with round or rectangular tubes. He also discovered that none used a space frame.

The preparations for the long-distance race were in full swing. Brakes are subject to particular loads and stresses in Le Mans, particularly on the four-kilometre straight between the Tertre Rouge and Mulsanne bends. In each lap it was necessary to decelerate from top speed to about 50 kph for these bends.

To reduce the load on the brakes, the idea took shape at Mercedes-Benz to use an air brake in the form of a tip-up aluminium flap. Experiments with a model in the wind tunnel at Stuttgart Technical University (STU) showed that the position originally planned for the brake flap on two pylons on the boot lid was not optimal.

As they would be lying in the slipstream of the coupé roof, they would not be getting sufficient exposure to the forward air-stream. STU suggested they should be attached to the rear end of the roof on pylons above the roof line. Though this made for a poorer cd value of 0.215 in the down position, in the erect position a cd of 0.9 was obtained.

At a speed of 240 kph this meant a deceleration of 3.4 m/s. At 120 kph the braking power was still a quarter of that at 240 kph. This force sufficed to push the flap back into its original position. The drivers found that the additional load on the rear axle which counteracted the axle load transfer during heavy braking was actually a pleasant side effect.

Looking and sounding impressive because their use created a dreadful noise, the brake flap was however not used. Its anchorage points in the tubular space frame could not long withstand the forces acting upon them. These tests were performed on vehicle 0006, which underwent an interesting metamorphosis in the course of its life.

For the race at Nürburgring this coupé became a roadster and was driven there by Theo Helfrich. Originally shipped to Argentina on 6 June 1953, the car today is owned by an American collector, who had the vehicle returned to its original state as a coupé with brake flap at the Mercedes-Benz Classic Center in Fellbach.

Another critical point was the question of entering the car. The rules said nothing against the small doors or entry hatches. In March Neubauer therefore contacted the marshal of Automobilclub de l’Ouest, Monsieur Acat. Acat provided a sketch with a proposal to extend the entry hatch downwards –and the gullwing door was born – a concession to the organiser and a means of avoiding any possible protests.

The 73 pages of rules for the 24-hour race specify in Article 34 Paragraph 2 that at least two permanent doors had to be fitted on either side of the body in such a way that both permitted proper and direct access to the front seats.

For Le Mans the fuel filler neck was extended through the rear window to the outside for faster refuelling. The cars were marked around the radiator grille with coloured rings to make it easier to distinguish between the individual teams of drivers.

The car with chassis number 0009 (No. 20 with Theo Helfrich/Helmut Niedermayr) was given a red band, car 0007 (No. 21 with Hermann Lang/Fritz Riess) a blue band, and car 0008 (No. 22 with Karl Kling/Hans Klenk) a green band.

After the start Ferrari and Jaguar took the lead. André Simon and Alberto Ascari took turns posting new lap records. But they overdid it. Two hours into the race, the clutch of Ascari’s Ferrari 250 S gave up the ghost. Simon in the Ferrari 340 America led, followed by Robert Manzon/Jean Behra in the 2.3-litre Gordini.

As evening approached, the two Frenchmen took over the lead and the last Jaguar had to throw in the towel. The American driver Carter in his Cunningham, powered by a 5.4-litre Chevrolet engine, suffered a similar fate. After a skid at Tertre Rouge he had to give up with damaged valves.

But everything was not going smoothly in the Mercedes-Benz pits either. There were signs of alternator damage in the 300 SL of Kling/Klenk. First Kling stood in the pits for ten minutes; an hour later another 17-minute wait was registered. At 12.30 that night, when Hans Klenk unstrapped his helmet with a look of resignation, the disappointment was deeply chiselled into his face.

The small, lightweight 2.3-litre Gordini still was in the lead. After a pit stop, Pierre Levegh in his 4.5-litre Talbot took over the lead. The 300 SL teams Helfrich/Niedermayr and Lang/Riess were running in second and third place 65 kilometres behind. By noon of the following day the field had dwindled to 19 cars.

Levegh was still in the lead, but stubbornly would not let his co-driver Marchand take his place. Behind him the two 300 SL stoically turned their laps with the precision of a Swiss watch. Seventy minutes before the end Levegh dropped out between Arnage and Maison Blanche with damaged connecting rods.

A case can be made that, fatigued, he overrevved his engine; his lap times, which had become very irregular, may be an indication of that. Front runner Theo Helfrich in his 300 SL lost his leading position during the early hours of the morning through a driving error which Hermann Lang immediately took advantage of. Mercedes-Benz won the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

Hermann Lang and Fritz Riess played a great part in this success and it was perhaps one of the most important wins of their careers. Team Helfrich/Niedermayr came in second in the second 300 SL.

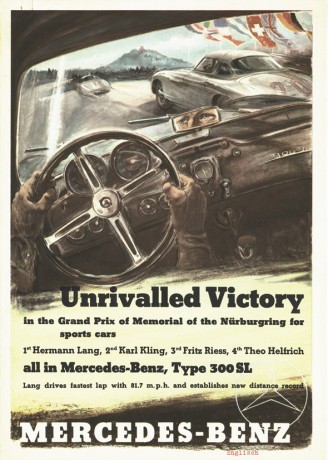

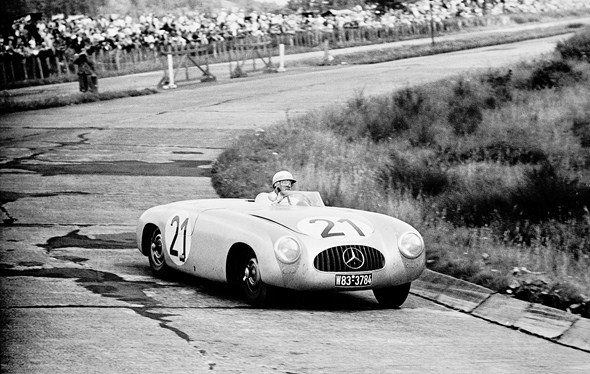

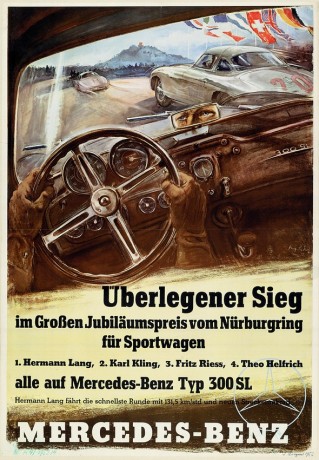

Nürburgring Anniversary Grand Prix, 3 August 1952

The Nürburgring Anniversary Grand Prix for Sports Cars was a supporting programme of the German Grand Prix. Even a sports car class for up to 8000 cc was set up to enable the start of two 219 hp (161 kW) 300 SL (W 194) cars with supercharged engines, which would have had to compete in that displacement class.

This engine was one new 300 SL feature. The second concerned the bodies of the sports cars. Only open-top vehicles were used in the race and so the 300 SL Roadster (W 194) made its debut at Nürburgring. Three of the four roadsters fielded for the race were made from existing coupés with their roofs cut off at the waistline.

That part of the gullwing door extending down the flanks now served as the entrance. The roadsters were 100 kilograms lighter than the coupés. These changes were made on the vehicles with the chassis numbers 0006, 0007, and 0009. The car with chassis number 0010 was reconstructed and differed from the other three roadsters by having different dimensions.

Its wheelbase was shortened from 2,400 to 2,200 millimetres; the track widths were also smaller than in the other vehicles. The slim roadster could be recognised by its slimmer radiator grille, which was supposed to improve the airflow. It had only 13 vertical bars in the grille compared with the usual 15.

During practice for the Grand Prix, roadster number 0010 was used to test the M 197 supercharged engine, among other things. The results of the lap times with supercharged engine, both in coupé No. 0004 and roadster 0010, were unsatisfactory.

Not because of the engine – that appeared to be hard-wearing enough, at least in the coupé which completed the test runs and the trip there and back between Stuttgart and the Nürburgring without any problems. Engineer Rudolf Uhlenhaut, who drove both cars, commented: “The familiar tendency of the normal swing axle to take a great deal of the load off the inside wheel, or to lift off during hard, tight cornering because of the high instantaneous centre of rotation, remains within tolerable limits in the 300 SL due to its wide track, relatively small wheels and moderate torque, except when the fuel tank is completely empty.

The reduction of the track width on the rear axle tested on one car did not really come up to expectations as – with little load on the vehicle and the driver sitting on the left – in sharp right bends the inside rear wheel would lift off too easily due to the even higher instantaneous centre of rotation.

This means that vehicles with a narrow construction are not practicable with the normal swing axle. When the supercharged engine was used in the 300 SL, the racing of the inside rear wheel made itself felt very unpleasantly. It prevented bends from being taken at high speeds and reduced the speed of the car. This is probably the reason for the disappointing lap times at Nürburgring. The better acceleration on the relatively short straights only sufficed to make up for the time lost on bends.”

For this reason, Board of Management member Fritz Nallinger and his experimental engineer, Rudolf Uhlenhaut, decided to stop using the supercharged 300 SL, not because there was no chance of victory in the specially established category up to 8000 cc – the 300 SL could easily have won against the weak competition – but they wanted to spare themselves the embarrassment of being only marginally faster than cars with naturally aspirated engines.

And so the coupé with chassis number 0004 remained the only SL to wear the designated No. 33, at least during practice. An additional 100,000 spectators trekked to the Nürburgring so as not to miss the sole race in the Federal Republic of Germany in which the SL was entered. It was possible to recognise the roadsters from a great distance by the different coloured diamonds on their wings and around the headlamps.

The driver-vehicle combinations were: Hermann Lang with car 0007 and No. 21 had blue diamonds (rhombi); Karl Kling with 0010 and No. 24, black; Fritz Riess with car 0009 and No. 22, red; and Theo Helfrich with 0006 and No. 23 had green diamonds.

After the start the spectators witnessed a gripping battle which no one had reckoned with. Robert Manzon in the 2.3-litre Gordini had already left Helfrich and Riess in the 300 SL behind him on the first lap. After overtaking Lang on the second lap, he then went after the leader – and that was Karl Kling. It was incredible how the suspense rose.

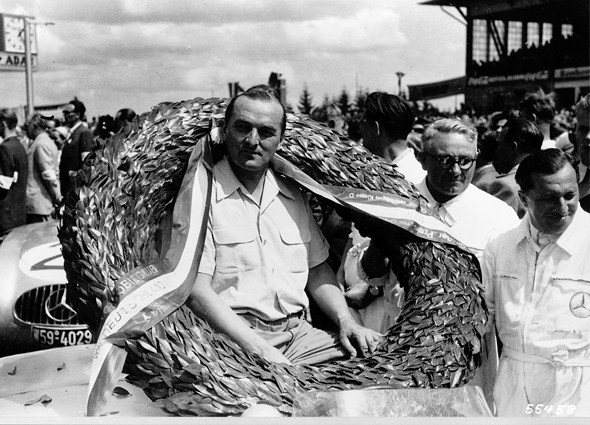

Driving with unleashed fury, the Frenchman managed to cut the gap to the leader from 20 to 7 seconds. But bad luck in the form of a defective transmission caught up with the valiant Manzon. Now the remaining four 300 SL could have enjoyed a boring Sunday afternoon stroll to the finish – but far from it.

Lang remembered his old skills and decided to go after the leader, his teammate Kling. During the pursuit, Lang turned in the fastest lap for a sports car of 131.5 kph and overtook Kling. Kling was dogged by misfortune, just as he was in Le Mans. His ignition timing went off and cost him engine power, and a crack in the oil filler neck allowed oil to drip onto the rear wheel.

An oily tyre tread is not a good condition for optimum roadholding on corners or straights. On the north loop of the Nürburgring, which no one as yet called the “Green Hell”, this definitely was an insurmountable handicap. And so for one last time the brave Karl Kling had to admit defeat to Hermann Lang, whose first-place finish on the Nürburgring was the last victory of his racing career. Riess and Helfrich landed in third and fourth place to complete the victorious quartet.

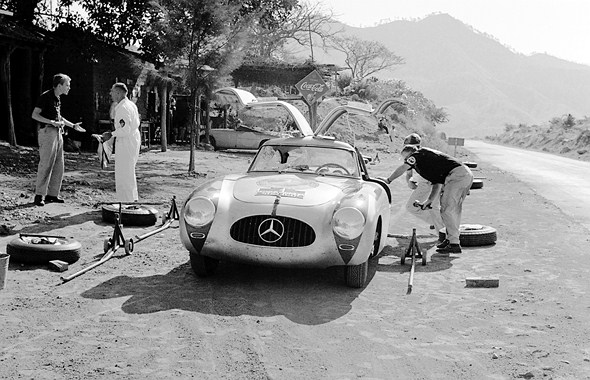

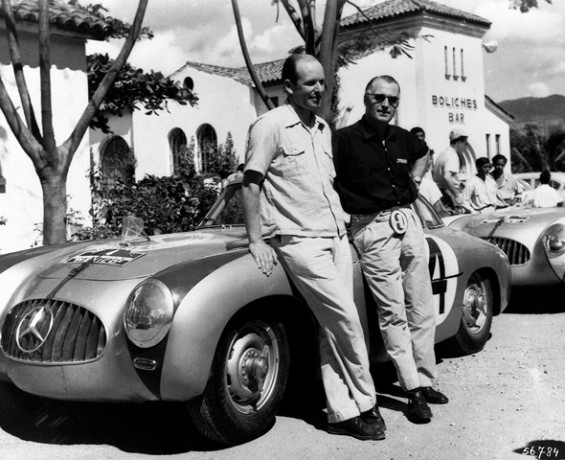

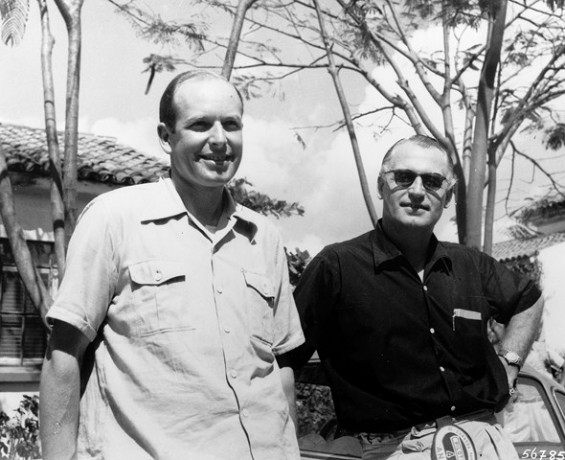

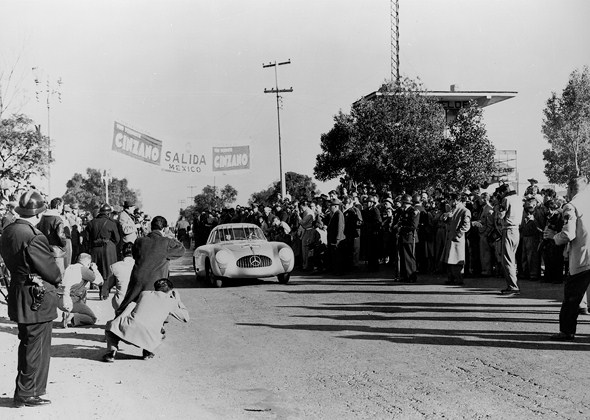

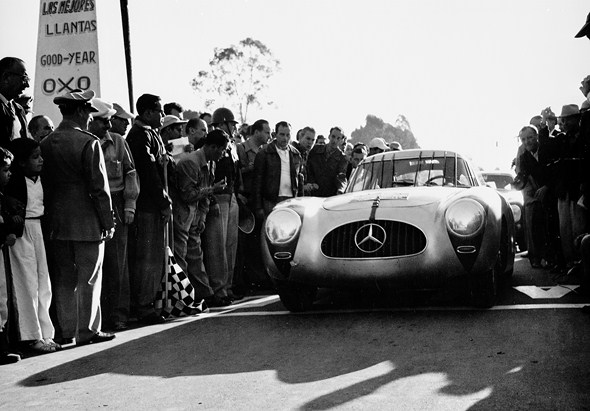

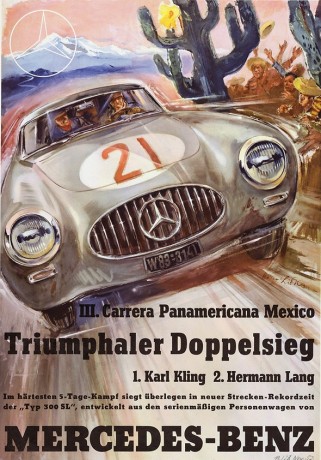

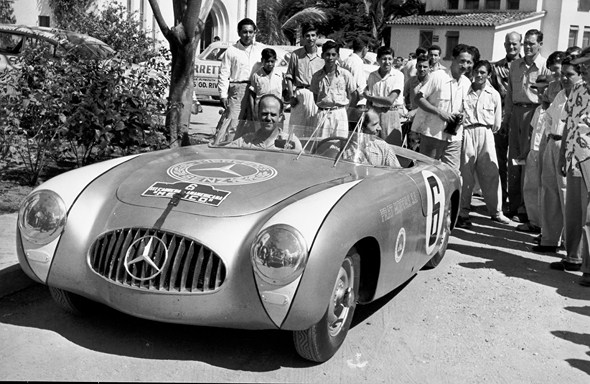

Carrera Panamericana Mexico, 19 to 25 November 1952

The adventure of the Carrera Panamericana in Mexico began for the 300 SL (W 194) two months in advance with high-altitude tests on Grossglockner Mountain – Grossglockner, because much of the course in Mexico lay at altitudes around 2000 metres above sea level. The highest point of the race at Puerto Aires pass was even 3,196 metres above sea level.

Finding the optimum carburettor setting posed a particular problem, because during the individual legs of the race there were repeated descents to 200-300 metres above sea level. At the same time, more power was needed for this long-distance race in Mexico.

Improvements to the combustion chamber and an increase in displacement to 3,105 cubic centimetres produced an output of 180 hp (132 kW) instead of 162 hp (119 kW). At the same time tyre tests were performed to determine when tread separation occurred in particular tyre makes and models. Because of the small 15-inch wheels and the poor supply of air within the streamlined body, tyre wear was especially high on the roads in Mexico, which had rough tarred surfaces.

In early October, a large “expeditionary force” set off for Veracruz in Mexico by ship. Along with the four 300 SL, the fleet consisted of two 220 Saloons and a 220 Cabriolet A, two 300 Saloons and a 300 Cabriolet D, a 300 S Cabriolet A, and two L 3500 trucks with a wheelbase of 4,200 millimetres.

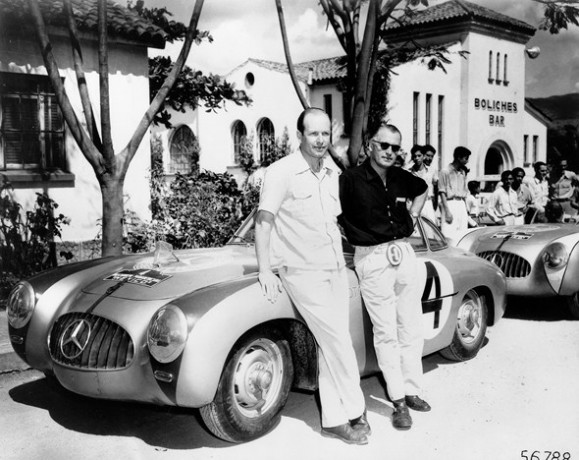

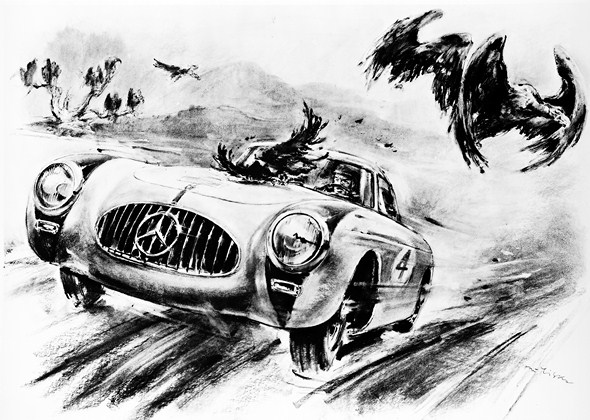

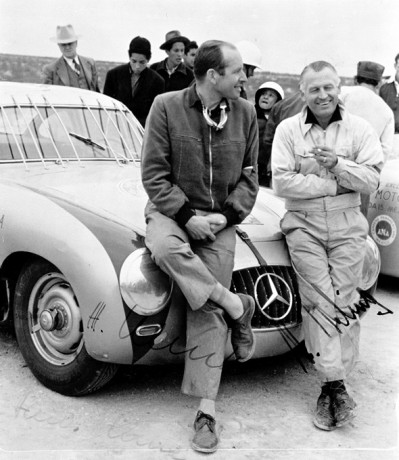

Three of the 300 SL were competition cars and one a practice car that was also used by racing manager Neubauer’s assistant, Günther Molter. The vehicles were allocated as follows: Karl Kling’s car 0008 (Coupé) with No. 4 had green rhomb-shaped strips around the headlamps; Lang’s car 0005 (Coupé) with No. 3, blue strips; John Fitch’s car 0009 (Roadster) with No. 6, white strips; and Molter’s car 0007 (Roadster), with no number, had blue rhomb-shaped strips around the headlamps.

First leg from Tuxtla to Oaxaca, 530 kilometres: at 7 a.m. sharp the first racing sports cars set off on the first leg to Oaxaca. Owing to the low competition numbers (lots were drawn for them), Lang, Kling and Fitch followed one another at short intervals. Hermann Lang ran into bad luck right from the beginning.

Only a few kilometres from the start a stray dog put a big dent in the wing of Lang’s car, which was doing 200 kph at the time. As the damage had to be inspected, Kling made the most of his chance and passed Lang. Lang was lucky that the steering of his car had not been damaged, but was unlucky in that he lost speed due to the damaged body.

But Kling’s luck did not last for long either. Tyre damage cost him his lead over Lang. Lang was able to recapture his old position. Generally speaking, all three Mercedes-Benz 300 SL were plagued by tyre problems, and all three had to replace a whole set of tyres three times. Mexico’s tarred roads have a surface which is mixed with granulated rock of volcanic origin.

It gives them extremely good grip, but drastically reduces the life of the tyres. With its 15-inch wheels, Mercedes-Benz had the smallest tyre size, while the Ferraris with 16-inch wheels and the lightweight Gordinis (only 750 kilograms) with 17-inch wheels were at a definite advantage.

The first leg saw the favourites drop out left and right. Robert Manzon had to shut down his Gordini because of an engine defect; Alberto Ascari in his Ferrari overturned; and Felice Bonetto tested the off-road capabilities of his Lancia when a tyre blew, which did not agree with his vehicle at all.

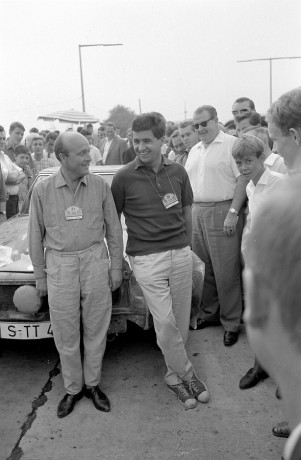

This was also the leg in which the collision of the 300 SL of Kling and Klenk with a vulture took place – some people say it was a buzzard. No matter what kind of bird it was that crashed into and went through the windscreen of the two as they were travelling at more than 200 kph, it hit the head of Kling’s co-driver Hans Klenk, who suffered a bloody laceration.

Kling “cured” the brief unconsciousness of his co-driver by violently shaking him, and when Klenk came round again he asked Kling to carry on. Once Kling had managed to stop the bleeding with a clean handkerchief, the two headed for the next depot.

The first leg was won by Jean Behra in a Gordini, who did not have to change tyres. Giovanni Bracco in a Ferrari was second, Karl Kling third, Umberto Maglioli in a Lancia fourth, followed by Jack McAfee and Luigi Chinetti in Ferraris. John Fitch and Hermann Lang were placed seventh and eighth.

The four vertical bars on each side of the 300 SL to protect against other low-flying poultry were the work of the resourceful and practical engineer Hans Klenk, who fitted them to the vehicle that same evening. The installation of a new windscreen was due to the private initiative of Mexican fan Luis Manjarrez.

When he heard about Kling’s mishap on the radio, he sent his driver to the Mercedes-Benz distributor in Mexico, had him pick up the windscreen there and fly it to Oaxaca in his private plane so that it could be fitted in the course of the evening.

Second leg from Oaxaca to Puebla, 412 kilometres: Jean Behra, driving alone, was the first to go out on the road in his Gordini. 50 kilometres before the end of the stage he overlooked a right-hand bend hidden beyond a hilltop and plunged into a gorge – that was the end of the race for the valiant Frenchman. Gigi Villoresi in his Ferrari won the second stage before John Fitch in the 300 SL. Kling and Bracco followed in third and fourth place. Hermann Lang was fifth.

Third leg, Puebla to Mexico City, 130 kilometres: after a break, this stage was tackled on the very same afternoon. Though only 130 kilometres long, it was a tough one. Puerto Aires pass, altitude 3,196 metres, had to be conquered on this leg. The low oxygen content of the air demands practically everything of humans and machines.

Here Kling had a depressing experience with the 4.1-litre Ferrari 340 of Gigi Villoresi, which had almost 100 hp (77 kW) more power than his car. After being overtaken by Villoresi, Kling tried to gain an advantage by staying in Villoresi’s slipstream, but couldn’t manage it. Villoresi simply accelerated and pulled away.

The first five finishers in order on the third leg: Villoresi, Bracco, Kling, Fitch, Lang. The interim overall standings in Mexico City listed Bracco in the Ferrari 250 S in first place, followed by Kling, Fitch and Lang, and in eighth place Villoresi.

Fourth leg, Mexico City to León, 430 kilometres: during the night of 20 November there was frenzied activity at the Mercedes-Benz distributors Prat Motors in Mexico City. The mechanics of the Untertürkheim racing department installed final drives with a higher ratio of 1 : 3.25 in all three competition cars.

The next stages all the way to the finish were mainly speed stages where high speed was most important. And there were no five-speed transmissions for the 300 SL which would have avoided an axle change. After the start in Mexico City and the ascent to the plateau, full-throttle passages showed the way to León.

Here Villoresi could again bring the superior power of his Ferrari America to bear. Even Bracco in his Ferrari 250 S was unable to keep up with him. And so the two red cars from Modena captured this stage, followed by Lang, Fitch, and Kling.

Fifth leg, León to Durango, 537 kilometres: this stage, a pure high-speed stage, was the longest in the competition; not only that, it was tackled after only a brief pause following the fourth stage. That too presented a special challenge to humans and machines. During the relatively brief break of half an hour, Kling made special preparations for what was to come.

Tired of the permanent problems with punctures, the seasoned, practical man relied on his long experience. He did not have new tyres fitted for the upcoming high-speed stage. Instead, from the used tyres he picked out the best. His reasoning was that these tyres were of such robust structure that they would continue to hold up – and he was right, as it turned out later.

This stage was the key to Kling’s victory. First, his biggest rival, Villoresi, dropped out with ignition problems. Kling won his first stage and also able to outdistance Bracco. Was a reversal of the duel at the Mille Miglia in the offing, where Bracco got the better of Kling? At any rate Kling moved along at such a pace that he was 22 kph faster than Ascari the year before.

The finishing order in the fifth stage: Kling, Bracco, Lang, Chinetti, Maglioli, McAfee, and Fitch. The next day again was marked by two half-stages over a total distance of 704 kilometres with long high-speed passages.

Sixth leg, Durango to Parral, 404 kilometres: the first half-stage was all about the contest between Kling and Bracco, in which Kling again emerged the winner. The next places were taken by Lang, Chinetti, Bracco, and Maglioli. At the start Fitch was disqualified for crossing the starting line and then returning to the pits. Since racing manager Neubauer accepted the disqualification, Fitch was allowed to continue and finish unclassified.

Seventh leg, Parral to Chihuahua, 300 kilometres: the next-to-last

stage was again fairly dramatic. At the start Bracco approached Kling and told him that his Ferrari had just about had it and Kling could go easy on his material. Bracco was a tricky fellow, but after 30 kilometres he had to call it a day with a defective differential. Hermann Lang also was struck by misfortune.

After a tyre change his gullwing door came loose and flew off. Owing to the dynamic pressure that built up inside the vehicle at high speeds, his rear window was also pushed out of its anchorage. It too flew away and landed somewhere in the Mexican Sierra. This explains Lang’s relatively poor time on this stage, although he nonetheless ended up in second place. Kling’s stage win again was undisputed and he crowned it with an average speed of 204 kph.

Eighth leg, Chihuahua to Ciudad Juárez, 370 kilometres: the last stage was a triumphal run for the Mercedes-Benz team. Kling, as official stage winner, averaged 213.5 kph; he was followed by Chinetti, Lang, Maglioli, and McAfee. Only Fitch was faster at 213.7 kph, but he drove out of competition and had nothing more to do with the final result.

With their double victory in the Carrera Panamericana Mexico, Mercedes-Benz with the W 194 succeeded in scoring what was probably the most important success for the brand in the 1950s, and one whose signal effect developed a tremendous impact that has lasted down to this day.

The sporting successes of the production sports car Mercedes-Benz 300 SL (W 198)

- Great achievements at international events

- Unforgettable: the Mille Miglia of 1955

- Roadster also used for motor sport

1955 was the big year for the 300 SL (W 198). After its debut a year earlier as a production car, it stirred up the scene in the big class of Gran Turismo cars as a newcomer in 1955. As expected, it made its first exclamation mark of the season in the 1955 Mille Miglia. But it wasn’t the only one. More were to follow until the end of the year when it won the European Touring Car Championship.

Mille Miglia, 30 April 1955

When people refer to the Mille Miglia of 1955, many people immediately think of Stirling Moss’s unforgettable victory in the Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR. Quite rightly so, but people are apt to forget the overall fifth place finish of John Fitch, who with co-driver Kurt Gesell won die Gran Turismo class over 1600 cc in the 300 SL (W 198).

Fitch even managed to outclass such formidable opponents as Sergio Sighinolfi in a Ferrari 750 Monza, the team of Wolfgang Seidel/Helm Glöckler in a Porsche 550 Spyder or Luigi Belucci in a Maserati A6GCS, all starting in the class of racing sports cars. Also in the Gran Turismo class, the team of Olivier Gendebien/Jacques Washer in a 300 SL (W 198) finished seventh overall.

Tulip Rally, 30 April to 7 May 1955

The Dutch team of Hans Tak/W. C. Niemöller won the 7th International Tulip Rally, which counted towards the European Championship.

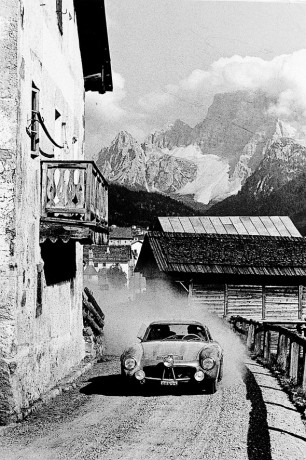

Coppa Dolomiti, 10 July 1955

Olivier Gendebien won the road race through the Dolomites in a 300 SL.

City of Lisbon Cup, 24 July 1955

The Portuguese Fernando Mascarenhas won the competition for the Cup of the Portuguese capital city.

Adria Rally

A first-place finish in the Adria Rally, which led through the Karst Mountains of Yugoslavia on roads that hadn’t ever seen a tarred surface, was an important step for the 300 SL and the team of Werner Engel/Heinz Straub towards winning the European Championship.

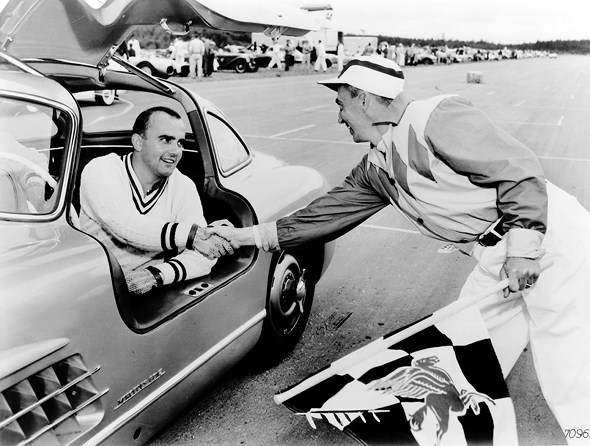

Swedish Grand Prix, 1 August 1955

As a supporting programme to the Swedish Grand Prix, a race for GT cars over 2000 cc was held in which Mercedes-Benz took part with two 300 SL driven by Karl Kling and Count Berghe von Trips. Kling won the race, while von Trips dropped out due to brake failure. Second place went to the Swede Erik Lundgren, who was supported by the company.

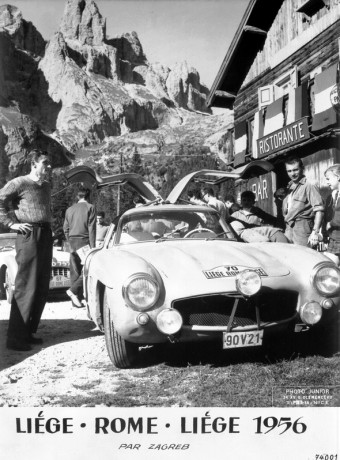

Liege–Rome–Liege, 17 to 21 August 1955

In five days it was not just a question of driving from Liege to Rome and back – no, there were a number of special stages scattered in between, leading across Alpine and Dolomite passes whose names awaken associations with holidays or the Tour de France. They included such illustrious names as Stilfser Joch, Gavia pass, Sella, Pordoi, and Falzarego pass, Colle di Tenda, Col de Brouis, Col de Braus, Col d’Allos, or the Galibier.

The Belgian Olivier Gendebien made especially intense preparations

for his participation in 1955, having competed in this hellish race in 1952 in a Jaguar Mk VII, in 1953 in a Jaguar XK 120, and in 1954 in a Lancia Aurelia GT, and coming in second in each of the last two years. This time he tackled it in a 300 SL with co-driver Pierre Stasse. An average speed of 50 kph was specified, reduced by 10 kph in comparison with the previous years.

On his fourth attempt Gendebien succeeded in winning the race by a surprisingly clear margin making 31 minutes and 49 seconds good on the required average. The second-place finisher managed 17 minutes and 48 seconds; the third, 16 minutes and 57 seconds. Werner Engel and co-driver Heinz Straub came in fourth to achieve another important step towards the champions’ laurels they had set their sights on.

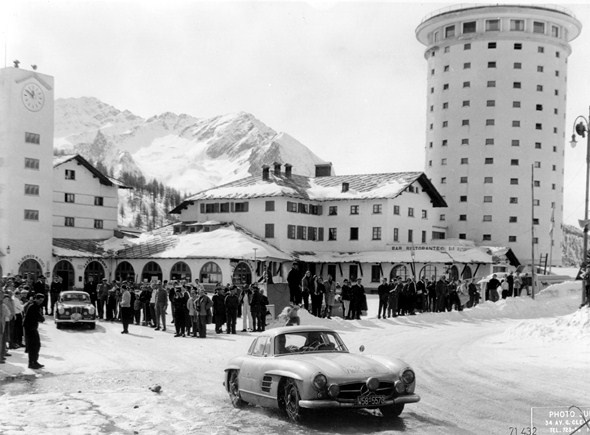

Stella Alpina Rally, 25 to 28 August 1955

Olivier Gendebien was in very good form following his big win in the Liege–Rome–Liege race, so the two-day Alpine rally just four days later was one of his easier tasks and it resulted in yet another brilliant victory.

Werner Engel was the European touring car champion of 1955. He captured this championship mainly driving the 300 SL. He competed in just two races, the Tulip Rally and the Nürburgring Rally, in a Mercedes-Benz 220 a.

Paul O’Shea captured his first US sports car championship in SCCA Class D in 1955 in the 300 SL.

The 1956 season

The 300 SL also seemed to have a monopoly on two championships in 1956: the European Touring Car Championship and in the USA the SCCA Class D Sports Car Championship, with Paul O’Shea.

But even though this may appear obvious to those of us reading

about it decades later, the European Touring Car Championship was actually a cliffhanger in the 1956 season. Success hung in the balance for the team of Walter Schock/Rudolf Moll. The championship was decided between two neighbours, one might almost say: between the Schock/Moll team in the 300 SL, both from Stuttgart, and Paul Ernst Strähle from Schorndorf, 28 kilometres to the east of Stuttgart, in a Porsche 1300 Super.

In the course of the season Strähle and his co-driver Hans von Wencher had doggedly worked their way forward towards the leaders. In the end, in a heart-stopping finale in the Rally Iberico on 4 November 1956, Schock/Moll became European touring car champions by a margin of just two points. Except for the Monte Carlo Rally where they drove a 220 a, they won the title driving a 300 SL.

The individual contests they won were the Rallye Sestrière and the Acropolis Rally. In the Monte Carlo Rally they came in second in the 220 a; in the Geneva Rally they took tenth place, in the Wiesbaden Rally ninth place, and in the Rallye Adriatique fourth place. Walter Schock also was German GT champion in 1956 with the 300 SL.

Two contests of 1956 deserve special mention because of their outcome. One is the Mille Miglia. In the big GT class the team of Prince Metternich/Count Einsiedel came in sixth ahead of Wolfgang Seidel/Helm Glöckler. But two other drivers in a 300 SL created quite a stir, at least until Rome: Wolfgang Count Berghe von Trips and Fritz Riess.

Heinz Ulrich Wieselmann, editor in chief of “das Auto Motor und Sport” magazine, reported at the time: “Young Count Trips, in a very good but absolutely standard SL, took over the lead of the general field in Pesaro, followed by Castellotti, Riess, who defended third place, Collins, Musso, Fangio, Moss, and Gendebien.

A big sensation appeared to be in the offing, even though Castellotti recovered the lead in Ancona; for very close behind him, and ahead of all other factory teams from Ferrari and Maserati, were Trips and Riess – in pouring rain, in normal SL sports cars, leading 300-horsepower red racing cars piloted by the best drivers in the world! However, the tide soon changed.

Trips took a double spin and flew off the road into a field without suffering any harm, and Riess fell increasingly behind after Rome as he had to stop and top up his water 19 times because of an assembly defect.”

Between 29 August and 2 September 1956 the Liege–Rome–Liege Rally was held again, the difference being that in 1956 it went to Zagreb in Yugoslavia and not to Rome; 5,065 kilometres over countless passes had to be covered in 90 hours. Once again it was the year of the 300 SL and of a Belgian – but this time not Olivier Gendebien, who had moved on to Ferrari.

No, in 1956 the Belgian Willy Mairesse won the gigantic rally together with his co-driver Marc Genin. He had acquired the Gullwing just three weeks earlier to take part in this rally. Second was the Frenchman Buchet in a Porsche Carrera, followed by the winner of the previous year, Gendebien, in a Ferrari 250 GT. The GT class up to 1300 cc was won by the team of Paul Ernst Strähle/Hans von Wencher in a Porsche 1300 Super – two persevering collectors of points for the European championship who didn’t quite make it in the end.

But the Gullwing was not only a successful rally or long-distance car that year; it was also good for GT points on racing circuits.

As a supporting programme to the German Grand Prix on the Nürburgring on 29 July 1956, races also were held for GT cars of various classes and the points counted towards the German GT Championship. In the class over 2000 cc an exciting battle for the lead developed between Walter Schock and Wolfgang Seidel, which in the end Seidel decided in his favour.

Third place was taken by Willy Mairesse, who had come from neighbouring Belgium for the race and was beginning to warm up with remarkable success in his newly acquired 300 SL. Fourth to sixth place were taken by Viktor Rolff, Bengt Martenson, and Arne Lindberg, also in the 300 SL.

At the Swedish Grand Prix on 5 August 1956 it was Bengt Martenson, Joakim Bonnier, and Wolfgang Seidel who took the first three places. Stirling Moss finished in second place in the Tour de France from 2 to 19 September 1956.

Wolfgang Count Berghe von Trips, Kurt Zeller and Wolfgang Seidel had a 1-2-3 finish in the big GT class in the Avus Race on 16 September 1956, which counted towards the German GT Championship. Walter Schock had to retire with a damaged suspension.

The 1957 season

1957 was the year of the change from the Gullwing to the Roadster presented at the Geneva Motor Show in the spring. For use in the USA in the SCCA Class D championship competition, two especially light and fast Roadsters were built in Untertürkheim specifically for Paul O’Shea; they were designated 300 SLS.

O’Shea managed a hat trick in this most important Daimler-Benz export market, winning the sports car championship of the USA in class D for the third time running with a 300 SL. Harry Carter won the class C championship in the Coupé.

The Dutch rally team Hans Tak/W. C. Niemöller took second place overall and won the big GT class in the 9th Tulip Rally, held between 6 and 11 May 1957.

In the Production Car Grand Prix of Spa on 12 May 1957, Willy Mairesse took the honours in the over 2600 cc GT car class, coming in ahead of Peter Nöcker. Both were driving Gullwings.

Four teams in the big GT class won the 1000 kilometre Race at Nürburgring on 26 May 1957. The order of finish: Fritz Riess/Walter Schock, Wolfgang Seidel/Peter Nöcker, Arne Lindberg/Erich Waxenberger and Bengt Martenson/Count Einsiedel.

In the hillclimb event on Mont Ventoux in the Provence on 30 May 1957, Frenchman Fontaine finished third in his class, and Geither won his class in the hillclimb race on Schauinsland outside Freiburg on 28 July 1957.

A major success was scored by Jo Schlesser together with his wife in the long-distance classic Liege–Rome–Liege, in which they not only won their class, but also took second place overall.

Arthur Pateman emerged as overall winner in the Macao Grand Prix (China); Kurt Zeller and Willy Daetwyler won their class in the Vienna Grand Prix.

On the Iberian Peninsula the team of Andres/Portoles was successful, winning the Rally España. The team of Santos/Huertas won the Caracas–Cumaná–Caracas Rally.

The racing successes of the Mercedes-Benz 190 SL (W 121)

- A sports version was available ex factory

- 190 SL pointed the way with a diesel drive and records

The 190 SL (W 121) was designed as a touring sports car by the factory right from the beginning. Succumbing to the urging of the American importer Maximilian Hoffman, for club sports events an optional version was supplied with lighter windowless doors and a small windscreen instead of the large one found in standard models.

In addition the bumpers and the soft-top could be removed to make the vehicle lighter and thus more attractive for sporting events.

From the outset the homologation of these vehicles under the sports laws presented a problem, since according to the regulations of the Féderation Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA) only cars that could be completely closed were recognised as Grand Tourisme vehicles. Since that was not the case with two small sports windows and lighter doors without windows, the 190 SL in this version was classified as a production sports car.

Against cars like a Porsche Spyder or Maserati 200 S it did not stand the slightest chance, of course. The same can be said of it in the normal version, which was classified by the FIA as a Grand Tourisme car. Racing manager Alfred Neubauer affirmed in a 1956 assessment that in an international field the 190 SL had no chance at all.

For example, a respectable lap time of 11 minutes and 58 seconds on the north loop of the Nürburgring, turned in by Arthur Mischke in the 190 SL, compared with a time of 11 minutes and 1.8 seconds in a Porsche Carrera driven by Schulze.

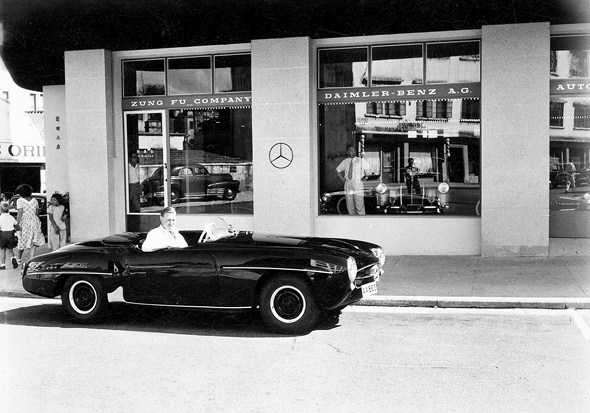

All the same, in 1956 the 190 SL scored a racing victory against such illustrious opponents as the Ferrari Mondial, Bristol Warrior, and Jaguar XK 140 with aluminium body and two Austin Healey cars in the Le Mans version. The occasion was the Macao Grand Prix, in which the enterprising Mercedes-Benz distributor Zung Fu Company Ltd. from Hong Kong entered a 190 SL in 1956.

The driving force behind this effort was the general manager W. M. Sulke, a racing enthusiast. Sulke had the Untertürkheim Testing department prepare two engines for him, obtained suitable suspension parts like springs, stabiliser bars and shock absorbers and used them to get a 190 SL ready for the race in his workshop.

In 1979, Sulke confirmed to Winfried Seidel, manager of the Dr Carl Benz Car Museum in Ladenburg, who made a replica of this 190 SL for himself: “Regarding the history of the 190 SL, we in fact had two 190 SL’s racing at the time. Both were largely modified here although the engines received some attention at the factory.” The effort paid off: Doug Steane finished the race, which was run in the rain, as winner with a lead of two-and-a-half laps over a Ferrari Mondial.

In the same year the Mercedes-Benz general distributor Joseph F. Weckerlé won the Grand Tourisme class up to 2000 cc in the Grand Prix of Casablanca.

The Mercedes-Benz 190 SL and diesel records

The diesel world records set with the 190 SL in the years 1959 and 1961 are remarkable and little known facts. In 1959, two well-known rally teams, Nathan/von Zedlitz and Kögel/Gastell, made attempts to break long-distance records for diesel cars. They felt the odds were in their favour to be able to better the 24-hour world record in the class up to 3 litres displacement.

They decided the 190 SL had a very suitable body for this project. One reason was that the petrol engine could be replaced by a diesel engine with identical dimensions and mounts without going to great lengths to convert the vehicle. A second reason was that the 190 SL provided the necessary basic requirements because of its drag coefficient.

They chose the fabric roof and not the hardtop in order to save weight. The Hockenheimring was selected as the course for making the record attempt. In those years this was still the old circuit with the relatively slow “city curve” passing the Hockenheim Cemetery. Considering that, it was all the more remarkable that they achieved an average speed of 124.1 kph. A two-litre OM 621 engine was used and enlarged to 2032 cc to get an output of 60 hp (44 kW) (so that it could be classed in the up-to-three-litre category).

In autumn 1961, a Mercedes-Benz distributor from Heilbronn, Walter Assenheimer, together with Hans Hölder, a well-known rally driver of that period, undertook record-breaking attempts in the 2-3 litre diesel class. For the 2-litre class, the performance of the OM 621 diesel engine was improved to 65 hp (48 kW) at 4700 rpm.

The vehicle was made radically lighter, with the roof, windscreen, bumpers, hubcaps, and the Mercedes star on the radiator grille being removed. A small windscreen in front of the driver was curved in a semicircle and wrapped far around to the side. The front passenger seat was covered with a metal sheet. Eight records were broken, and the highest speed, 150.6 kph, was attained over a mile with a flying start. The other records were as follows:

1 kilometre, standing start: 98.6 kph

1 mile (= 1.609,30 m), standing start: 111.7 kph

1 kilometre, flying start: 150.0 kph

1 mile, flying start: 150.6 kph

5 kilometres, flying start: 142.3 kph

5 miles (= 8.046,50 m), flying start: 136.2 kph

10 kilometres, flying start: 137.5 kph

10 miles (= 16.093,00 m), flying start: 134.9 kph

For the records in the class up to three litres they installed a 2035 cc engine. They were slower with it than with the smaller two-litre engine, but still faster than the team that had set the records two years earlier who had also used the 190 SL as a basis. This meant that they had succeeded in breaking these records, too.

The Mercedes-Benz 230 SL (W 113) in sporting action

- Successful in demanding rallies

- Inseparably bound up with the name of Eugen Böhringer

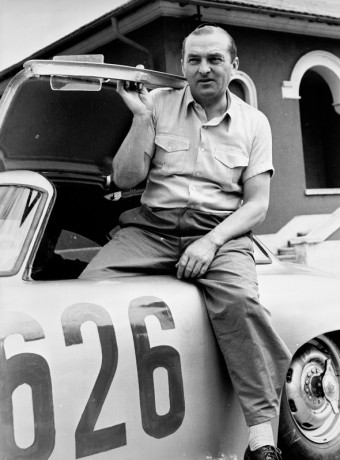

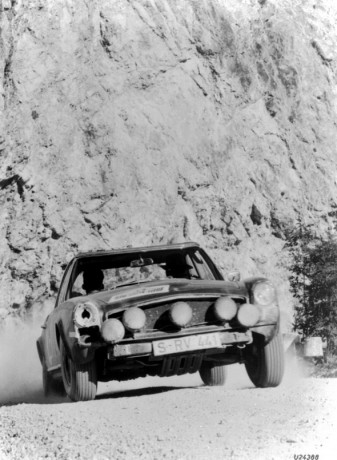

On three occasions the Mercedes-Benz 230 SL (W 113), the “Pagoda”, saw service in extreme rallies. The very first time it scored a resounding success. This was due to the imaginativeness and self-assertiveness of a single man: Eugen Böhringer. Actually the red rally “Pagoda” ought to be christened the “Böhringer Coupé”, because in rally use, for safety reasons, of course, it was run only as a coupé with a permanently fitted hardtop.

But before that could happen, Böhringer had to run an obstacle race of a special kind – through all the decision-making committees of Daimler-Benz AG, all the way to the Board of Management.

The starting point for the use of the 230 SL in competitions was the vehicle scheduling for the 1963 rally year. Karl Kling and Eugen Böhringer, European champions of the previous year, analysed the options for the best use of vehicles, tailored to the particular courses. After all, one really wanted to win the European championship again.

Based on his experience, for the upcoming Spa–Sofia–Liege Rally, a rally he had won the year before, Böhringer requested the 230 SL as a rally car. He expected to gain advantages from the short vehicle’s manoeuvrability in the Alps with their countless passes and on the winding, dusty roads in the Balkans.

The only problem was: this car didn’t exist yet – at least, not officially. It was going to be presented to the public at the Geneva Motor Show in early March 1963. But this was not an obstacle to put Eugen Böhringer off. He got an appointment with Board of Management member and Chief Engineer Fritz Nallinger to present his case to him.

Nallinger, himself a successful participant in minor races and reliability runs in his early years – he even won the Swiss Alpine Trial in a Benz 16/50 hp Sport in 1924 – and was willing to listen to material arguments. And he was a shrewd tactician who knew how to get critical items through the Board of Management. He persuaded Böhringer to put his arguments personally to the Board.

That would be more convincing than a proposal coming from him, Nallinger. Böhringer, by nature a person with a good measure of fearlessness, not only when driving a car, then presented his arguments on the occasion of the presentation of the 230 SL at the Geneva Motor Show to the Board members present there. As foreseen by Nallinger, he did not of course only meet with approval.

The Board member responsible for Production, Wilhelm Langheck, argued, for example, that there were already so many ways to throw money away that one did not need another one. But after Böhringer’s convincing presentation Nallinger succeeded in getting the blessings of the Board for the rally assignment of the 230 SL.

And so in the testing department, a 230 SL was configured for rally use under the direction of Erich Waxenberger. Since homologation as a Gran Turismo car could not pushed through before the beginning of the rally due to its small production numbers, the 230 SL started in the sports car category.

The team of Eugen Böhringer/Klaus Kaiser won the rally with the new car at first go. At the International Motor Show in Frankfurt am Main in autumn 1963, the “Pagoda”, still in rally look, graced the Daimler-Benz exhibition stand at the German premiere of the 230 SL.

Eugen Böhringer was so satisfied with his “dancer” – as he liked to call the 230 SL because of its manoeuvrability, but also because it did not have the unwavering straight-line stability of a big saloon – that for the coming year another 230 SL was configured for rally use. It was lovingly nicknamed in Swabian dialect: “Des kloine Scheißerle” (the little bugger).

In 1964, Böhringer/Kaiser drove the new car in the Spa–Sofia–Liege Rally. Perhaps they would have done better to use the 1963 car. A defective cable cost them 25 minutes and lost them the lead. To crown it all, a sheep got in the way of the team as it rushed along and, apart from reparable bodywork damage, it caused the loss of the left headlamp.

This was a severe handicap during stages driven at night. They reached the finishing line in Liege in third place. And Eugen Böhringer, as winner of the previous two events, received a gold cup in honour of the most successful driver of the past years.

In 1965, Dieter Glemser competed with the 230 SL in the Acropolis Rally. While in the lead, he was sent in the wrong direction by a policeman and lost so much time that he had to be satisfied with fifth place.

The Mercedes-Benz 500 SL (R 107) for motor sport

- For weight reasons, open-top vehicle constructed for the 1981 rally season to follow SLC Coupés

- Walter Röhrl was already engaged – but withdrawal from motor sport at the end of 1980 put an end to all activities

For the 1981 rally season, serious consideration also was given to the use of the SL of the R 107 series (1971 to 1989). The SLC Coupé (C 107) used up until then was too heavy and above all too long and unwieldy. Accordingly, under the direction of Erich Waxenberger, extensive modifications were made to the substance of the SL.

Sheet metal was used for the roadster’s floor assembly with a thickness corresponding to that of the saloon understructure. This saved around 60 kilograms in weight. Another 40 kilograms were saved by omitting comfort-related parts. Adequate torsional strength for the body was obtained through the (obligatory) installation of a safety cage and by bolting the roof to the body at seven points. These alterations contributed about 40 kilograms in additional weight.

The performance of the engine was improved by a number of changes. The engines used to up to then in the SLC developed up to 305 hp (224 kW), but this was no longer sufficient. In the course of the year the engine developers under Heinrich Reidelbach conjured up another 24 hp (17.6 kW). The 340 hp (250 kW) suspected by the press at the time were not yet available as the test certificates of the period prove.

With the sudden withdrawal from motor sport in December 1980 – Walter Röhrl already had been taken on for the coming season –, the issue of the rally SL was settled. Some of the rolling stock still on hand was sold to Scuderia Kassel.

A year and a half later, Norbert Haug, then head of the Sport department of the magazine “auto motor und sport”, was given the opportunity to drive and measure the performance of one of the 500 SL cars in rally version. With the low drive axle ratio of 1 : 4.08 it went to 100 kph in 5.9 seconds and got a top speed of 220 kph.

Haug was impressed and deserves to be quoted: “The last living dinosaur is wild, heavy, and roars. Its fighting mates are extinct; its rivals are lighter, faster and more agile – but not more powerful. The dinosaur comes from a good family, so its fathers don’t like to see it wading through mud roaring.

The driver of the silver-coloured two-seater knows no stress – a Daimler is still comfortable even in rough terrain and with firm springs and dampers. And by the way, the monster has power enough to spare and it is let loose on the rear wheels by a four-speed automatic transmission that can be manually shifted.

The driver, sitting in a plastic Recaro seat weighing only four kilograms, can forget first gear, because in first the high-torque sports car only scrapes its drive wheels excitedly. In second gear it makes lively progress. One should steer into bends very early, for since the rally Daimler is a very resolute understeerer owing to its nose-heaviness, even with the front wheels turned it is inclined to zoom straight ahead, unimpressed.

But if the driver is able to perform the artistic counterdrift-drift practised by rally specialists, then things can be fun in the Daimler cockpit: the car only has to be brought into a good angle to the direction of travel before reaching the bend. And then all it needs is for the driver to touch the accelerator and make light steering movements and he has everything needed for fast cornering.”

And so the last competition SL became a car that was a real pleasure to drive, but which could no longer demonstrate its true qualities.