- Stature and style, combined with technical progress and outstanding comfort

- The history dates back to the origins of the car

Stuttgart – The representative vehicle boasts a distinguished appearance befitting its status. For an imposing car that makes a big impression does not merely serve as an end in itself as it transports passengers.

Through its very presence it has the effect of reinforcing impressive appearances – whilst it is true to say that appraisals will inevitably vary, depending on the particular epoch in question and the cars used in each case.

They are always also a reflection of their time, and a representative car does not just impress with its stature and style; it often documents technical progress, too, and is admired for its outstanding comfort.

The tradition of representative vehicles from the Mercedes-Benz brand and the predecessor companies Benz & Cie. and Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft (DMG) is a story characterised by various interruptions.

Having said that, up until 1981, the year in which production of the Mercedes-Benz 600 finished, it was absolutely indisputable that the brand had to be present in the exclusive vehicle category.

Around another two decades would pass before the then DaimlerChrysler AG once again established itself in the high-end segment: with the Maybach brand in 2002.

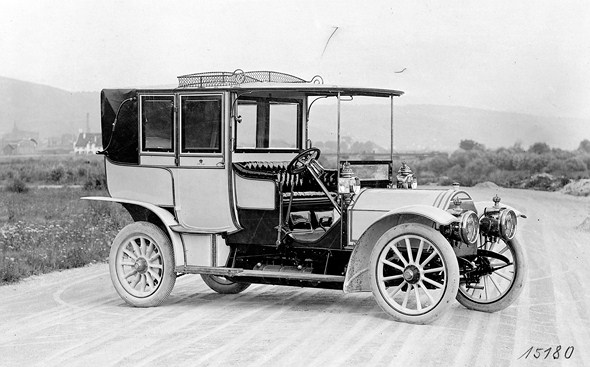

The era of representative vehicles began at the beginning of the 20th century, some twenty years after the invention of the automobile.

It was initiated by the same circle from the wealthy bourgeoisie that made a name for itself as sponsors of motor racing.

The businessman Emil Jellinek, for instance, was one of the friends and promoters of the car who repeatedly made significant contributions to the vehicles’ advancement by providing some valuable food for thought in the early days.

One of the results of this work was Jellinek’s 1907 touring car, which can now be admired in the Mercedes-Benz Museum, and which already embodied some of the fundamental characteristics of a representative vehicle.

When he had a touring car built, Jellinek, who was always wont to think a little further ahead than many of his contemporaries, did not opt for one of the widespread tourer or phaeton carriages.

Instead he chose a comfortable, imposing saloon, which – with an engine output of 60 hp (44 kW) – was in the upper echelons of the model hierarchy of the day.

In contrast to many of his peers, Jellinek even thought of the driver, who was also protected from the elements by a fixed roof, doors and windows.

It should be pointed out here that back in those days the open carriage was the usual body form and the closed vehicle the special, exclusive variant, and in many cases this applied up until the end of the 1930s – for representative cars, too.

The nobility, predominantly lovers of horses and coaches, only discovered the car for representative purposes after the moneyed bourgeoisie. Tsar Nicholas, for example, is reported to have been a riding enthusiast who valued old customs – but not the car, at least not to start with.

The German Emperor Wilhelm II is said to have had a similar attitude. Nevertheless the automobile gradually found its way into the aristocracy’s stables and slowly but surely turned them into car parks.

Representative cars up until the First World War

- Included in the fleets of VIP customers

- Individual bodies on the plant chassis were the norm

- Highly technical cars

As early as at the end of 1905, Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft (DMG) delivered five Mercedes-Simplex 45 hp with various bodies to the court of the Tsar in St. Petersburg.

Along with other customers of high rank, the Tsar was never satisfied with owning just one vehicle; the tsarist fleet is also said to have included a Benz 60 hp and a Mercedes-Knight 16/40 hp.

Over the years, as well as various Mercedes-Simplex, the German Emperor’s fleet came to include three Mercedes-Knight, a Mercedes 28/95 hp, a Mercedes 15/70/100 hp and a Mercedes-Benz 770 ‘Super Mercedes’ Cabriolet F from 1932.

Today the latter is on display in the Mercedes-Benz Museum, along with the 1935 armoured Pullman saloon of the same model, owned by the Japanese Emperor Hirohito.

By 1912 Benz & Cie. numbered the German Emperor, the Russian Tsars and the Swedish Royal Family amongst its most famous customers.

The sports-enthusiast brother of the German Emperor, Prince Henry of Prussia, was not only the founder and patron of the Prince Henry Tours named after him, as well as being the inventor of the windscreen wiper; he himself often took part in events in his open-top 70 hp Triple Phaeton.

A particularly impressive car was the Model 39/100 hp, built by Benz in the years 1912 to 1915. Because of its dimensions and clear lines it signalled a sense of noble distance.

However the shock caused by the global economic crisis of 1907 led to Benz becoming established as a high-profile provider of vehicles to the lower middle class, but without losing sight of the spectrum of representative cars.

It was with this concept that Benz succeeded in positioning itself clearly ahead of DMG in the period before the First World War in terms of the number of vehicles produced.

At DMG the dominant top-range car from 1910 to 1914 was the Model 37/95 hp. With its prestigious presence, its owners – who were often members of the aristocracy – were able to cut a grand figure. In 1913 the chassis came with a price tag of 23,000 Marks – the usual base price of the time.

Then either the plant would fit an individual body to this or a body assembler would carry out the work. This was where the car manufacturers were in competition with the finest body assemblers of the day.

With its large-piston four-cylinder engine with 9.5 litres of displacement and a chain drive system, however, it represented a dying form of automotive technology.

For a period of many years, particularly in the case of vehicles with powerful engines, the cardan drive system was favoured over chain drive due to the gentler power transmission.

In 1914 it was replaced by the Mercedes 28/95 hp. As a premium-segment vehicle it took its leave of the four-cylinder engine and the chain drive system, like the Benz 39/100 hp.

The six-cylinder engine, created by Paul Daimler, was built with a design largely based on that of the 1912 DF 80 aircraft engine, which was awarded the ‘Emperor’s Prize’.

The engine had V-shaped overhead valves, which were operated via an overhead camshaft and rocker arms. The camshaft was driven from the front end of the crankshaft by a vertical shaft.

Due to the war only 25 units of Model 28/95 hp were manufactured during the years 1914 and 1915. Production started up again after the end of the war, when Paul Daimler took the opportunity to have the engine revised.

The individual steel cylinders were replaced by cylinder blocks cast in pairs, but the coolant jackets welded in pairs remained. The valves which been open up until then were now sealed with oil-tight light-alloy valve covers for each cylinder pair.

The mixture was supplied via two Pallas updraught carburettors, which each fed three cylinders. The two intake manifolds, again Y-shaped, were connected with each other via a balance pipe to ensure even mixture supply.

Following the First World War, the target groups of potential customers changed – the aristocracy diminished in importance in this respect, with personalities from the fields of economics, film, theatre, politics and industry taking its place.

The Mercedes 28/95 hp remained in existence until 1924; there were 590 vehicles in all. Whilst the term ‘Super Mercedes’ was not coined until after its time, it was certainly deemed to be worthy of this description.

The number of units built was substantial, especially bearing in mind the prevailing circumstances and compared with vehicles of a similar profile which would follow in its footsteps.

But this imposing vehicle also served to cover a wide customer spectrum due to the fact that there were three different wheelbase versions, which meant that it was not restricted to just large saloons or open-top touring cars.

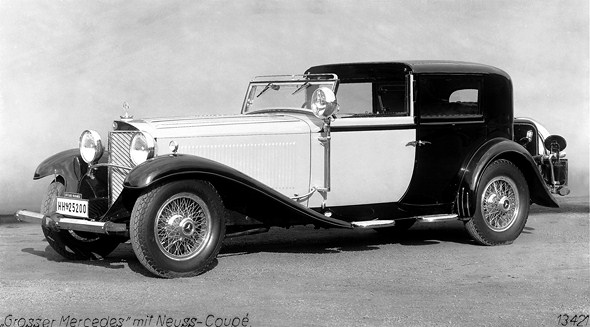

Mercedes-Benz Model ‘Super Mercedes’ (W 07),

1930 up to 1938

- A new landmark among premium cars, also available in a

special-protection version

- Superb handling in spite of its conservative chassis design

- Available with and without supercharging

‘With this model Germany’s automotive manufacturing industry regained its place at the forefront of the special segment, which had actually always been Germany’s domain right from the beginnings of automotive engineering – coupled with the name Mercedes-Benz.

One can safely assume that it is precisely those circles which always consider that only the very latest in excellence are just about sufficient for their requirements will focus their interest on this model.

’ That was the conclusion drawn by the editor of the renowned ‘Allgemeine Automobil-Zeitung’ (AAZ) in 1930 about the ‘Super Mercedes’ unveiled at the Paris Motor Show. This was the official name of the Mercedes-Benz Model 770.

Around the end of the 1920s, the time was ripe for Mercedes-Benz to set a new landmark in the premium car segment.

The Model 630 was no longer in keeping with the times, and Daimler-Benz was in danger of losing its standing in the top car class in view of the Maybach 12 model with a V12 engine (7-litre displacement, 150 hp/110 kW) which was brought out at the end of 1929 by its competitor Maybach, and the Zeppelin 8 model presented at the Paris Show a year later (8-litre displacement, 200 hp/147 kW).

However, because of the brand’s reputation and also its recent in-house experience, Daimler-Benz was very careful when it came to new technical features. In 1932, the specialist publication ‘Motor und Sport’ reported on this matter on the occasion of the ‘Super Mercedes’ test:

‘In contrast to the American view, which is in favour of the V-engine of the 12- or 16-cylinder type as far as representatives of this price category are concerned, they have remained remarkably sober in giving the Super Mercedes an eight-cylinder in-line engine.

With a vehicle whose fundamental tendency is towards exclusivity to such a great extent they thought that any excursion into uncharted waters would be fatal. That is how the new design from Daimler-Benz came to be a happy avowal of traditional links.’

It is true that from a technical point of view, the ‘Super Mercedes’ – known internally as W 07 – did not constitute a great leap forward into the realm of new technologies.

There was certainly much expectation amongst the general public surrounding the Mercedes-Benz 170 (W 15) which came out a year later in 1931, with its advanced chassis including independent suspension.

But despite its conservative chassis design with front and rear rigid axles, the new top model surprised people with its clear handling as a result of skilful suspension tuning. ‘Motor und Sport’ proves revealing here, too:

‘The Super Mercedes is certainly a fast car. With its saloon body it achieves a speed of 150 km/h. This kind of output is seen as racing-driver speed in many circles.

We know of vehicles, even more recent ones, in which it would be reckless to drive at over 70 km/h, whereas there is no such limit where the Super Mercedes is concerned.

In contrast to some statements made by the competition which have come to light, the conduct of the Super Mercedes at all speeds is beyond reproach.

Whilst the car’s springing is not as sensitive as it is amongst the American competitors, the Super Mercedes enables a sure driving style that secures cohesion with the road.

We do not know of any vehicle that would allow such safe driving with heavy bodies at the breathtaking speed of 120 km/h. And this is probably where the ultimate sense and the ultimate justification for the existence of this vehicle model are to be found.

In spite of its orthodox fundamental philosophy, the Super Mercedes presents itself as the worthy conclusion of Daimler-Benz production and as the final enhancement of automotive comfort achievable with today’s means.’

The criticism of large cars’ handling was indeed an issue back then; on another occasion the testers found fault with the handling of the Cadillac V16 and Maybach 12, which were direct competitors of the ‘Super Mercedes’:

‘The rather unpleasant lateral swaying of the body would be dealt with by strengthening the slightly soft springs and by tightening the shock absorbers and would then probably cease; however the question remains whether the springing would be sufficient on poor rural roads – which predominate on long journeys – to retain the high average.

As is the case with the new twelve-cylinder Maybach, it is very apparent here that future work must concentrate on improving the handling.’

The ‘Super Mercedes’ was the last very conservatively characterised new design from the still young Mercedes-Benz brand, which came about in 1926 as a result of the merger of the companies Benz & Cie. and DMG.

The expectations that had manifested themselves in society with regard to an exclusive car from this brand turned out to be an advantage for it, its place in automotive society having been carved out by the predecessor models.

Advanced engine with supercharging

The 7.7-litre eight-cylinder unit with its in-line design was a progressive, solid engine when compared with the eight-cylinder variant in the Nürburg model, but it could not be classed as sophisticated when compared with the engine in the forerunner of the Model 630.

In comparison with the international competitors, one special feature did remain: the vehicle could be equipped – as an option at that time – with a supercharger which increased the output from 150 hp (110 kW) to 200 hp (147 kW).

Another special feature of the W 07 model series was the fact that the car was available without a compressor with a deletion allowance of 3000 Reichsmarks. 13 customers availed themselves of this opportunity.

The overhead valves were operated by a low-mounted camshaft via tappets and rocker arms. The cylinder head made of grey cast iron was sealed by an electron valve cover.

The engine block of grey cast iron chromium-nickel alloy housed the crankshaft with nine bearings and was closed off at the bottom by an electron sump. The cylinder head contained eight spark plugs for the engine which worked with combined battery and magneto ignition.

For the naturally aspirated and belt-driven supercharger version the mixture was supplied via an updraught twin carburettor with an accelerator pump and choke. When the engine was cold the starting procedure was also made easier by preheating of the intake manifold.

The transmission represented a special feature, as an overdrive could also be selected in addition to the usual three forward gears, making a total of six forward gears available.

The overdrive was preselected via a lever on the steering wheel, and activated by briefly decelerating without pressing the clutch. The same method was used for shifting down.

Throughout the entire construction period the ‘Super Mercedes’ of model series W 07 had the two final-drive ratios i = 4.5 and i = 4.9 at its disposal.

In the case of the early vehicles, lubrication of the chassis was carried out automatically via a central lubrication process which involved the engine oil being pumped out of the sump at the appropriate points of lubrication.

On the later models the usual central lubrication employed at Daimler-Benz then was used, whereby every 100 kilometres the tappet of a pump which had to be operated by foot supplied the lubrication points with oil.

The low-frame chassis offset at the front and rear with cross bracing in the centre consisted of closed U-section steel side members.

The front axle, a rigid axle made of chromium-nickel steel with an H-section and the rear rigid axle were connected with the frame by long semi-elliptic springs and were supported in their springing work by lever-type shock absorbers.

Where the early vehicles were concerned, changing the wheels was a tiresome business: the 2.7-tonne car had to be raised manually using a jack. Later cars offered a built-in hydraulic hoist which raised individual wheels.

The wheels used were variously-sized wire spoke wheels or what were known as artillery wheels. The latter were wood spoke wheels which had originally been used for heavy artillery canons. 7.00 x 20 low-pressure tyres, 190 x 20 ‘giant pneumatic tyres’ and 8.25 x 17 low-pressure tyres were used.

What was striking during the production period of this ‘Super Mercedes’ was the change in body style that took place within this time, which spanned nearly eight years.

To start with there were still very sharp-edged bodies with upright windscreens and tail ends without boots, but over the course of time more rounded shapes developed, as did windscreens which were positioned at more of an angle and what were at first boots merely added on, before they were finally integrated into the overall shape.

The wheels were also quite isolated, particularly the front wheels, as they were only covered by a curved sheet metal panel serving as a wing. As time went by, the wings too, with their deep aprons and the wheels they housed, could be seen more as an integral part of the overall design and gave the side view of the body a more homogeneous appearance.

It is also interesting to note that the top speed of the final models was raised from 150 km/h to 160 km/h – without increasing the engine output – a modest success achieved by rounder bodies.

A special feature in the range of Mercedes-Benz passenger cars was the multifunction steering wheel with five additional functions: these included sounding the horn using the signal ring, turning up and dimming the lights via the button (adorned with the brand emblem featuring the star and laurel wreath) positioned in the centre of the steering wheel, and control of the fuel/air ratio, ignition and overdrive functions which were operated via three levers.

According to the 1931 brochure the range of bodies on offer comprised the Pullman saloon, Cabriolet D, Cabriolet F and open-top touring car.

The 1935 brochure depicted the following body versions: Pullman saloon with a rear-deck luggage rack, Cabriolet D with a boot, Cabriolet F with a rear-deck luggage rack and an open-top touring car with a rear-deck luggage rack.

| Prices for the ‘Super Mercedes’ (W 07) in the years 1930 up to 1936 | |

| Chassis | 32,500 RM |

| Pullman saloon, 6 windows, 4 doors, 7 to 8 seats | 41,000 RM |

| Open-top touring car, 6 windows, 4 doors, 7 to 8 seats | 42,000 RM |

| Cabriolet C, 2 windows, 2 doors, 4 seats | 44,500 RM |

| Cabriolet B, 4 windows, 2 doors, 4 seats | 47,500 RM |

| Cabriolet D, 4 windows, 4 doors, 4 seats | 47,500 RM |

| Cabriolet F, 6 windows, 4 doors, 7 to 8 seats | 47,500 RM |

| Deletion allowance without belt-driven supercharger | 3,000 RM |

In 1937 and 1938, the chassis of model series W 07 was then on sale for 24,000 Reichsmarks.

By setting this more favourable price the company was reacting to the significant decrease in demand that there had been since 1936 in view of the advent of the new ‘Super Mercedes’ of model series W 150, with its considerably more up-to-date technology.

The prices are those given in the brochure and to a certain extent they should be regarded as orientation values, as hardly any vehicles produced were identical, and Cabriolet-F bodies with a boot and the Cabriolet C not listed in the brochure were also supplied.

The following are examples of body assemblers who delivered bodies for the ‘Super Mercedes’ (W 07):

Auer, Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt

Erdmann & Rossi, Berlin-Halensee

Josef Neuss, Berlin-Halensee

Papler, Cologne

Reutter, Stuttgart

Voll & Ruhrbeck, Berlin-Charlottenburg

VIP customers included:

German Reich Chancellery, Berlin

Wilhelm II of Hohenzollern, former German Emperor, Apeldoorn/Netherlands

Emperor Hirohito, Japan

Archduke Josef, Budapest

Admiral Miklós Horthy, Budapest

Germany Embassy, London

Otto Wolff, Cologne, industrialist and Member of the Supervisory Board of Daimler-Benz AG from 1926 to 1940

Lord Mayor Karl Fiehler, Munich

Federico J. Vollmer, wholesale merchant, Hamburg

Axel Tidstrand, Sågmyra/Sweden

In total, 119 vehicles of the ‘Super Mercedes’ (W 07) model were sold between 1930 and 1938; the number of units was spread as followed:

42 Pullman saloons

26 open-top touring cars

18 Cabriolet D

8 Cabriolet F

4 Cabriolet C

2 Cabriolet B

19 chassis, of which 4 were sold to Erdmann & Rossi

13 vehicles of these were supplied without a belt-driven supercharger

Another point to note is that there was never any such model as a 770 K, which has cropped up in the literature from time to time. The model designation is always: Mercedes-Benz Model 770 ‘Super Mercedes’.

This also applies to its successor, the model series W 150 presented in 1938.

On the path towards the model series W 150 there were small quantities of an interim vehicle, the model series W 24, of which six cars were built for the Reich government.

From the exterior it corresponded to a great extent to the early versions of the ‘Super Mercedes’ of model series W 150 and is often confused with it. From a technical point of view, however, they were worlds apart.

As its source of power the model series W 24 had the 5.4-litre supercharged engine of the Model 540 K, which had an output of 115 hp (85 kW) without support from a belt-driven supercharger and 180 hp (132 kW) with supercharging.

As far as the structure of the chassis was concerned, it was a hybrid design, which underlined this vehicle’s interim status: the frame was a box section frame, as was the case for all the large Mercedes-Benz models up until then.

At the front the W 24 model series still had a rigid axle with semi-elliptic springs, but the rear axle was a modern DeDion axle with coil springs, which was used at the instigation of passenger car design engineer Hans Gustav Röhr, who had recently arrived on the scene.

This design became the precursor of the DeDion rear axle which was later to be used in the W 150 model series and which was always referred to at Mercedes-Benz as the parallel wheel axle.

The vehicles belonging to model series W 24 never went by one of the usual official model designations; internally they were occasionally referred to as ‘540 K (long wheelbase)’. Nothing is known of the whereabouts of the cars delivered to the Reich government.

Mercedes 24/100/140 hp, 1924-1926

Mercedes-Benz 24/100/140 hp, 1926-1928

Mercedes-Benz 24/100/140 hp Model 630, 1928-1930

- A belt-driven supercharger gave output a significant boost

- Numerous body variants were available ex factory

Paul Daimler left DMG in 1922 in disagreement with the Supervisory Board. It had called for easier-to-sell models in the lower price ranges, whilst Daimler wanted a new model with eight cylinders.

His successor was Ferdinand Porsche, who had come from Austro Daimler. He had already taken over from Daimler once before, at Austro Daimler’s forerunner, the company Austrian Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft mbH in the town of Wiener Neustadt.

What was not known at the time was that Porsche’s main development focus was also more on large and expensive cars rather than small and lower-priced models.

So in hindsight it is not surprising that the first project Porsche undertook was to design a representative twin model series of new luxury vehicles with displacements of 4 litres and 6.2 litres.

The only differences between the two were to be found in the swept volume of the engines, in the wheelbase, the overall length and a few points of detail in the body.

The length available for the body on the chassis and the technically sophisticated basis were identical. The larger engine required a wheelbase that was 120 millimetres longer and resulted in the chassis weighing 100 kilograms more.

Porsche followed his previous convictions at DMG, too, believing that a good and powerful engine also had to be aesthetically pleasing. For the new six-cylinder engines he adopted the basic concept that he had also used for his engine designed at Austro Daimler, from that company’s Model AD 617.

The common features were the light silumin-cast crankcase with drawn-in dry cast cylinder liners, the crankshaft with only four bearings and the removable cylinder head with an overhead camshaft, which used rocker arms to operate the valves positioned in line via valve levers.

The camshaft was driven by a vertical shaft driven from the clutch side. Together with the manual transmission the engine formed a cohesive component and thus at the same time a huge functional block.

It comprised all the levers required to operate the car, including the steering gear and the steering column with the steering wheel.

Fitted to the transmission were the starter, the air pump for inflating the tyres in case of damage to them, the hand levers for the gearshift and handbrake plus the pedals for the clutch and brake.

For his new designs at DMG, which arrived on the market in 1924, Porsche adopted the principle of supercharging which had been introduced by Paul Daimler.

The positive-displacement belt-driven supercharger, with a high-ratio design of around 1 : 3, was located at the front end of the engine in a light-alloy housing fitted with cooling ribs.

It was switched on by pressing down the accelerator, similarly to the kickdown position familiar from today’s automatic transmissions, via a multiple-disc clutch.

When the accelerator was released it was slowed down by a multiple-disc brake located on the crankshaft.

For the two large touring cars Porsche used the principle of the pressure carburettor engine – situated between the belt-driven supercharger and the combustion chamber – which had long been championed at Daimler-Benz.

An early form of the multifunction steering wheel

The characteristic features which stood out at that time compared with the passenger cars produced up until then were the removable cylinder head, the dry multiple-disc clutch in place of the double-cone clutch with a leather gaiter used thus far, the slightly pointed nickel-plated honeycomb radiator instead of the previous more deeply contoured and painted pointed radiator, the introduction of an actuating ring on the steering wheel for operating the horn by pressing the upper part of the ring and the dimming device by pressing the lower part of the ring, and the internal expanding brake for all four wheels.

In Porsche’s two-passenger car with a 4-litre and 6.2-litre engine, the Model 24/100/140 hp with the larger unit was the driving force – not in terms of the number of vehicles built – the smaller and less-expensive car retained the upper hand there.

But when it came to the image factor – esteem, as people would say in those days – the car with the brawny engine was clearly the more representative vehicle.

Over the years changes were made to the model designation.

To start with it was called the Mercedes 24/100/140 hp, and then after the merger in June 1926 Mercedes-Benz 24/100/140 hp. In 1928 it became the Model 630, as the previous rather cumbersome name was not much of a purchasing incentive, and also the aim was to introduce uniformity with the Stuttgart, Mannheim and Nürburg vehicle names, which were also given a model number which corresponded to the displacement.

The larger engine had a displacement of precisely 6240 cubic centimetres, which, strictly speaking did not justify the figure ‘630’ in the model designation which was supposed to refer to the displacement.

For nearly 100 years, history served up a parallel episode: the V8 engine installed by AMG today is also called a 6.3-litre engine, although it has a displacement of 6208 cubic centimetres.

In October 1928, the Model 630 was upgraded, whereby the more powerful engine with 160 hp (118 kW) from the K model was also supplied as an option for the normal touring car.

In the plant’s documentation this variant was described as the ‘Model 630 with a K engine’ or ‘6-litre car with a K engine’. This combination assumed the flagship position in Daimler-Benz AG’s passenger car range up until the ‘Super Mercedes’ appeared on the scene in October 1930.

It developed into the somewhat more durable variant, and – eventually – also the more sought-after one. Production of the chassis and car with the 140 hp (103 kW) engine ceased in 1929, that with the 160 hp (118 kW) K engine a year later. Naturally this did not exclude so-called stock vehicles from only being sold and registered much later.

As the years went by some changes were made so as to keep the vehicles up to date. These included those carried out in 1926 to replace the rear cantilever springs by semi-elliptic springs, which were fitted beneath the rear axle from the outset.

From autumn 1927 the three metal tubes were added as trim for the exhaust pipes which ran on the outside of the bonnet at that time, and from October 1928 customers could choose to have the aforementioned engine from the Model K installed – just in the open touring car at first but then later in all the other body variants too. This was followed in 1928/29 by the inclusion of a Bosch-Dewandre brake booster.

As development continued there were only minimal changes to the range of bodies on offer. Particularly impressive features by current standards include the two open-top touring cars with five or seven seats, which were also available with an attachable saloon body in the style of a present-day hardtop. Between 1926 and 1928 the spectrum of bodies available and the pricing was as follows:

| Prices for Model 24/100/140 hp | |

| Chassis | 19,250 RM |

| 5-seater open-top touring car | 23,800 RM |

| 5-seater open-top touring car with removable Pullmanroof structure | 26,500 RM |

| 7-seater open-top touring car | 24,000 RM |

| 7-seater open-top touring car with removable Pullmanroof structure | 26,750 RM |

| 6/7-seater coupé | 26,750 RM |

| 6/7-seater fixed Pullman saloon | 27,750 RM |

From 1929 onwards, the range of bodies was reduced, but the more powerful K engine could be ordered for an additional charge of 2,000 Reichsmarks (RM).

| Prices for Model 24/100/140 hp – Model 630 | |

| Chassis | 19,250 RM |

| 6/7-seater open-top touring car | 24,000 RM |

| 6/7-seater Pullman saloon with wide door pillars | 25,000 RM |

| 6/7-seater Pullman saloon with narrow door pillars | 27,750 RM |

| 4/5-seater interior-drive cabriolet | 26,500 RM |

| 6/7-seater Pullman cabriolet (special version) | 28,000 RM |

The bodies were manufactured either at the Sindelfingen plant or, as was the norm back then, especially where premium-segment cars were concerned, purchased from internationally renowned body assemblers in accordance with customer requirements.

In this case special requests were then met, such as the extra-high Pullman saloon for Reich President Paul von Hindenburg, so that on official occasions he was able to wear his spiked helmet and in civilian dress his top hat inside the vehicle.

Hindenburg also had a Pullman cabriolet at his disposal. Both cars were specially designed at the Josef Neuss car factory in Berlin.

The following are examples of well-known and renowned companies which supplied bodies for the Mercedes-Benz 24/100/140 hp Model 630:

Balzer, Ludwigsburg

Castagna, Milan

D’Ieteren Frères, Brussels

Erdmann & Rossi, Berlin

Farina, Milan

Geissberger, Zurich

Hibbard & Darrin, Paris

Million Guiet, Paris

Josef Neuss, Berlin-Halensee

Papler & Sohn GmbH, later, Papler GmbH, Cologne

Van den Plas, Brussels

Saoutchik, Paris

Voll & Ruhrbeck, Berlin-Charlottenburg

Zschau, Leipzig

VIP customers included:

Reich President Paul von Hindenburg

King Gustav of Sweden

King Alfonso of Spain

Emil Jannings, actor

Richard Strauss, composer

Richard Tauber, singer

Jan Kiepura, singer

Oscar R. Henschel, industrialist

In total, 1080 vehicles of the Mercedes-Benz 24/100/140 hp Model 630 were constructed between 1924 and 1930. In addition to this, there were also 117 vehicles with the powerful K engine.

Mercedes-Benz Model ‘Super Mercedes’ (W 150), 1938 up to 1943

- Sophisticated chassis with independent suspension at the front and DeDion axle at the rear

- A longer wheelbase facilitated larger body variants

- Special-protection variants were also available

The creation of the new ‘Super Mercedes’ with the internal designation W 150 began at around the end of 1936 and can be attributed to two circumstances: on the one hand the increased demand from industry and government circles for a more modern premium vehicle, and on the other hand the realisation that the existing ‘Super Mercedes’ model with its conservative suspension including rigid axles at the front and rear plus a chassis of the type found in the very early days of the automobile no longer met the standards laid down by Daimler-Benz AG.

There was also the fact that by then the entire range of passenger cars and racing cars – with the exception of the Nürburg model – had been changed over to designs which included front and rear independent suspension and that since 1931 when it built the Model 170, Mercedes-Benz had been a major protagonist in the arena of advanced passenger car chassis.

Daimler-Benz was even already appearing on the international stage as a licensor for the progressive front suspension with two trapezoidal links and coil springs.

Even the American motor industry, which tended to be more reserved in such matters, was now using this front suspension.

It was above all a challenge facing design boss Max Wagner: to come up with an up-to-date chassis for the new ‘Super Mercedes’, and the experience gained when redesigning the W 125 and W 154 racing cars proved valuable to him

. As was the case with the latter models, for the new ‘Super Mercedes’ he used a chassis made of pipes as a longitudinal member. At the front axle this had trapezoidal links of unequal length and coil springs, and at the rear what was known as a parallel wheel axle – a DeDion axle with coil springs.

The thrusts at the rear axle were absorbed by V-shaped front-facing members, which were pivoted on the centre transverse pipe.

The outer longitudinal members made of pipes were curved far downwards in front of the rear axle in order to achieve a low centre of gravity.

The longitudinal members were connected to six transverse pipes which were pierced and welded with the longitudinal members.

In conjunction with the large shock course for the spring, this torsionally rigid design with bending resistance resulted in excellent road holding, which was unusual amongst such big and heavy luxury cars.

This was illustrated by a quotation from the only test report of the time, which appeared on 23 May 1939 in the British magazine ‘The Motor’: ‘Normally a limousine of this size will not be driven in a spectacular manner. We did some fast travelling on winding roads and the general standard of handling and road holding is undoubtedly very good indeed.

The car holds its course admirably through fast bends, and the absolute rigidity of the tubular chassis is well reflected in the road holding.

Although no ride control is employed, the suspension system provides a good combination of soft riding in town with steady cornering and freedom from excessive roll on the open road, and the whole car gives an impression of considerable stability.’

But it was not merely the chassis design that made such a difference compared with the predecessor – the larger dimensions played a part too. The wheelbase increased by 130 millimetres, the track width at the front increased by 100 millimetres, and at the rear by as much as 150 millimetres.

And so the task of the body designers working under Hermann Ahrens was to create lighter, more spacious bodies, whose length grew by an extra 400 millimetres, making them precisely 6 metres long. But the vehicle weight also increased with the size.

Whilst the brochure for model series W 07 still referred to 2700 kilograms, the weight for model series W 150 went up to between 3400 kilograms and 3600 kilograms – also according to the brochure.

And in some cases it did not stop there. For the special-protection version as a six-seater, 4400 kilograms of mass had to be set in motion – as much as 4550 kilograms in the case of the even more heavily armoured four-seater. The engine output was also increased for these weights.

In the naturally aspirated version the engine output increased by 5 hp (3.7 kW) to 155 hp (114 kW), with a switched-on positive-displacement blower by 30 hp (22 kW) to 230 hp (169 kW). The shafts of the outlet valves were filled with sodium salt for better cooling.

The three-speed transmission from the predecessor with engageable overdrives did not survive in the successor either. It was superseded by a four-speed transmission with a fifth gear as a high-ratio overdrive.

So as not to be punished by shorter refuelling intervals with the increased engine output and significantly higher weights, the tank capacity went up from 120 litres to 195 litres.

For what was the world’s largest representative vehicle when it entered the market Daimler-Benz gave the top speed as 170 km/h, though this was drastically cut to 80 km/h for the heavily armoured versions with their bullet-proof twenty-chamber tyres.

Superb performance

This is what ‘The Motor’ wrote about the performance and top speed of the conventional Pullman saloon in 1939:

‘Changing gear gently, without the second-saving brutality that has normally to be employed for test purposes, it proved possible to cover the standing quarter-mile in 21 seconds.

From a standstill to 50 mph took 12.2 secs. and to 60 mph. 17 secs., which suggests the standard of performance available without necessarily indicating the absolute maximum results obtainable.

Cutting the blower in for a quarter of a mile sufficed to raise the speed from 75 mph to 87 mph, demonstrating its value in maintaining high averages after temporary checks.

Timed over a quarter of a mile, the car clocked 100 mph. With some ease, carrying four people; indeed, it was accelerating along the Railway Straight at Brooklands.

The speedometer is very nearly accurate erring slightly on the side of slowness lower down the range, and the ultimate readings obtained suggest that the absolute maximum speed is in the region of 108 mph, a truly impressive velocity for an eight seater limousine weighing 3 tons.’

The career of the ‘Super Mercedes’ (W 150) unarguably suffered due to the Second World War, which began shortly after production started.

This was also borne out by the body variants produced: the open-top touring cars favoured by the government dominated, in stark contrast to the predecessor model, for which more civilian bodies had been made, such as cabriolets and Pullman saloons.

The bodies for the ‘Super Mercedes’ (W 150) were manufactured solely at the special vehicle production facility in Sindelfingen, which also met exclusive requirements.

The designation ‘Sindelfingen body’ became a seal of approval in vehicle construction. The best-known example of this was the Cabriolet B, which was built as a one-off specimen for the heir to the Persian throne and is now a valuable item in the possession of an American collector.

Further special features included the various special-protection versions which existed in the familiar body forms, both open-top and closed.

Vehicles with an armoured windscreen could be recognised by additional exterior slits which were linked up with the heating and ensured clear windscreens.

Over the course of a special campaign during the war by order of the government calling for specially armoured vehicles (‘Aktion P’), ten four-door and four-window saloons were built. As has already been mentioned, they were even heavier than the special-protection Pullman saloons. Their windo