- Beginnings as a cuckoo’s egg at the Mannheim plant

- The backbone of truck production during difficult times

- A precursor to the successful L3250 model

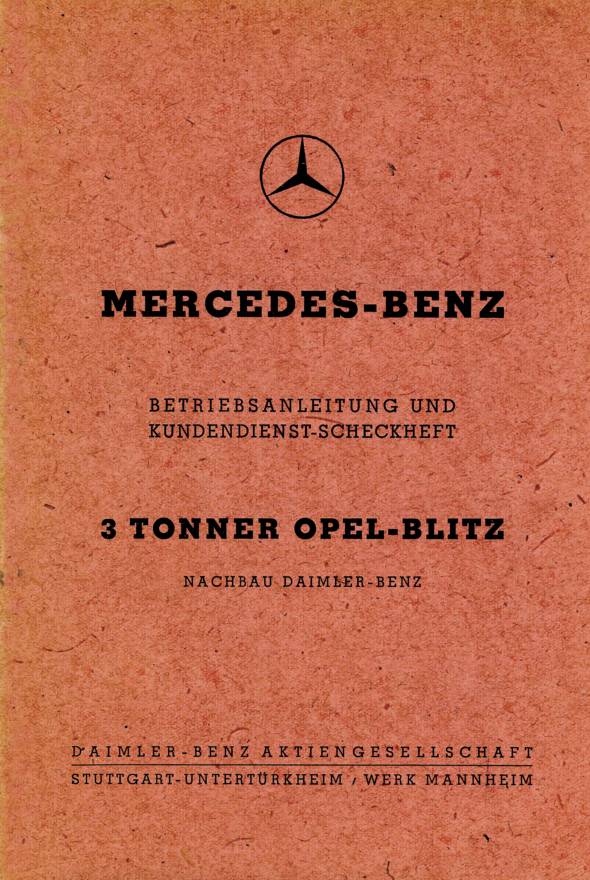

Stuttgart – The 1948 Mercedes-Benz owner’s manual for one of the most unusual vehicles ever to leave the company’s production halls referred to it as the “three-tonne Opel Blitz”, with the addendum “Daimler-Benz licensed reproduction”. Colourful in character despite a less than glamorous appearance, and ground-breaking at the same time, the three-tonne Opel Blitz was given the designation L 701 at Mercedes-Benz. And, presumably all too mindful of its alien DNA, the company decided against issuing it with any kind of company logo.

The plant relaunched production of the L 701 for civilian use in June 1945, having built the vehicle there for approximately six months on behalf of the military.

But the colourful aspect to the story was this: that when you are suddenly obliged to build a rival model in your own production halls – thereby marginalising the in-house product – it necessarily leaves something of a bitter taste.

Economical diesel versus lively petrol engine

The two bestsellers in the medium-duty segment in the pre-war years bore either the name Daimler-Benz or Opel Blitz. The Opel Blitz impressed with a lively petrol engine; on the other hand, the three-tonne Daimler-Benz model won on weight with its economical if rather sedate diesel unit.

The reproduction version of the Opel Blitz built for the post-war period would prove pioneering, because the licensed-version of the Opel Blitz ultimately presented Daimler-Benz with an opportunity to proliferate – both in terms of the vehicle and production.

Military insists on the Opel Blitz

The story has its origins in the 1940s. The Opel Blitz had made a name for itself not only in civilian life but also as a military vehicle. Its high payload and excellent off-road properties impressed the army to such an extent that armaments minister Speer decided the only vehicle required in the three-tonne class was the Opel Blitz. Furthermore, this ruling would be applied not only to the Opel plant at Brandenburg, but also at Borgward and Daimler-Benz. When the agreement was concluded in 1942, a one-off payment of 800,000 Reichsmarks was made to Opel to make licensed production legally binding.

This put a temporary end to efforts already under way at Daimler-Benz to produce a comparable vehicle to compete with the Opel Blitz. Although Chairman of the Board of Management Wilhelm Kissel had been calling for “a truck with a load capacity of three tonnes that was as light and cheap as the Opel Blitz” since 1938, his proposal was not given the attention required for an overhaul of the company’s truck programme.

The in-house diesel model is sidelined

The unwelcome situation that had to be faced was that the in-house three-tonne diesel was simply overweight. With a gross vehicle weight of 6.7 tonnes, it had a payload of just 3.1 tonnes. By comparison, the Opel Blitz replica, as produced by the Mannheim plant from August 1944, had a load capacity of 3.3 tonnes and tipped the scales with a GVW of 5.8 tonnes. In times of materials shortages, such factors played a particularly important role, since three Opel Blitz models could be built for the same contingency weight as two Mercedes-Benz L 3000 models.

However, after concluding the licensing arrangement almost exactly two years would pass before production could begin. For one thing, Daimler-Benz management was angered at being ordered to build a foreign product and mothball its own model. Opel had successfully and prudently refused to create the necessary capacity to accommodate the higher production figures specified by the highest authorities, since that would inevitably have led to dangerous overcapacity in the post-war period.

But there was no way out: Daimler-Benz and Borgward would be obliged to produce the Opel Blitz in parallel. Nevertheless, the view was gradually taking hold at Daimler headquarters in Stuttgart that some good may ultimately come from switching to the Opel Blitz. Indeed refusal could lead to the plant being forced to convert to production of war materials other than motor vehicles – and the possibility of being marginalised for ever in terms of truck production.

So eventually the Board of Management – much to the annoyance of its chairman Wilhelm Kissel – finally endorsed Opel Blitz production at Mannheim.

The importance of staying on the ball

Wilhelm Haspel, a member of the Board of Management (and from August 1942 Kissel’s successor as chairman) was quick to recognise that truck production was “of paramount importance for the post-war period, since if ever we were to stop it would be very difficult to restart vehicle production.”

In any case the company had no reservations about using an Opel Blitz chassis to test new in-house developments, including for example an air-cooled prototype engine named the OM 175. During 1943 one such Opel Blitz conversion openly underwent testing on the roads.

Nevertheless, measures needed to adapt production to the new vehicle proved less than straightforward. The wartime economy made it difficult to get hold of the required production equipment, and in addition there were problems integrating new production lines into the existing, fully equipped factory (particularly as these went against directives for ongoing production of the in-house model).

In addition, the Opel plant at Brandenburg was one of the most advanced of its kind in Europe; and it required a colossal effort to calibrate the Mannheim factory to Opel’s particularly lean and efficient workflows. Ultimately, however, the plant stood to benefit enormously from this modernisation.

Mannheim suddenly has a monopoly

These were the reasons why the start of production was two years in the making. But even when the moment finally came in August 1944, production processes were slow. Total output reached just 3,500 units before the Third Reich collapsed (around six months later), By this time, however, Mannheim was the only supplier of the Opel Blitz. Production at Opel’s Brandenburg plant had been brought to a standstill by bombs in early August 1944 and the Allied air raids also meant that nothing came of planned production at Borgward.

What Daimler-Benz in Mannheim supplied to the German army was the Opel Blitz licensed version, complete with the rectangular standard army cab made of wood-fibre panels that had long since replaced the original Opel steel cab so as to economise on valuable metal.

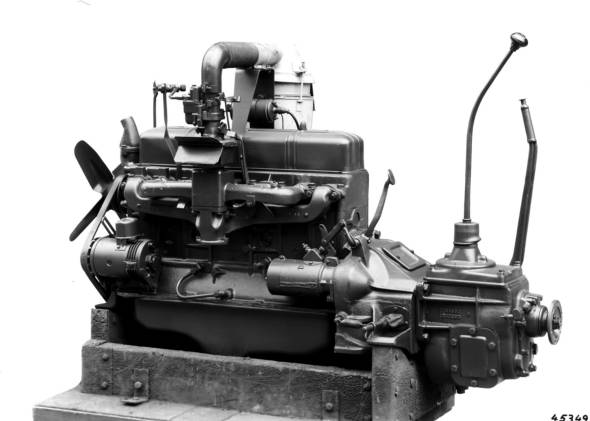

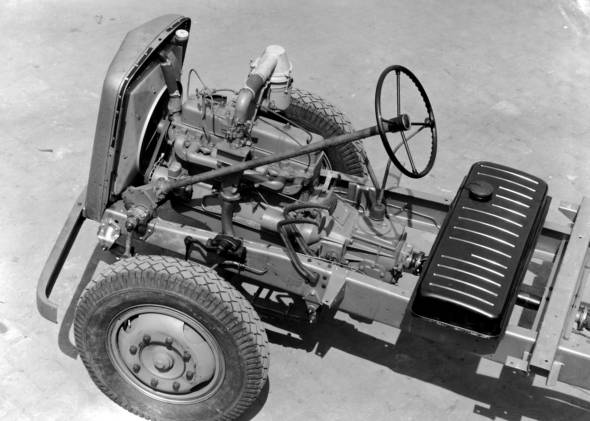

The army design of 1942, the vehicle which Daimler-Benz was now required to produce, essentially differed very little from the Opel Blitz that had been in production since 1930. It featured a stiffer rear suspension, an oil bath air filter for the engine and output had been downrated from 55 kW to 50 kW for a more efficient torque curve.

Before the standard army cab replaced the original steel version, however, a further small but significant modification was made to the driver’s cab – in keeping with the wartime situation. As a result of the growing number of partisan attacks the Opel Blitz was hastily equipped with a raised roof.

The reason for this measure was to enable crews to sit in the cab in an upright position with helmets on, since guidelines now recommended the wearing of a steel helmet while travelling aboard the truck.

Licence agreement twice extended

Originally with a term that ran until the end of the war, the licence agreement provided for Daimler-Benz to produce the Opel Blitz not only in the conventional wheelbase version of 3600 millimetres, but also the S version with a wheelbase of 4200 millimetres and an all-wheel-drive variant. It was also planned that Daimler-Benz would supply Opel with engines for its “Admiral” saloon. None of this came to fruition.

Nevertheless, the licence agreement was extended on two occasions. For when the war came to an end, the Mannheim plant had escaped relatively unscathed and could consider itself fortunate that production of the L 701 was still intact. Downtime was relatively brief. The plant was occupied by units from the 7th US Army on 11 April 1945, and by May 1945 truck production in Mannheim had started up again – if rather tentatively at first.

Probation as the backbone of production

In Mannheim Daimler-Benz had at its disposal production facilities that were largely intact and state-of-the-art (and moreover paid for by the state). Consequently the L 701 would clearly dominate truck production at Daimler-Benz until its replacement by the L 3250 in1949. In 1946, for example, a total of 1,497 units of the L 701 came off the production line at Mannheim, whereas Gaggenau production of the 4.5-tonne L 4500 totalled just 522 units. And in 1948, Mannheim produced 3,803 examples of the L 701, while Gaggenau turned out 884 units of the L 4500.

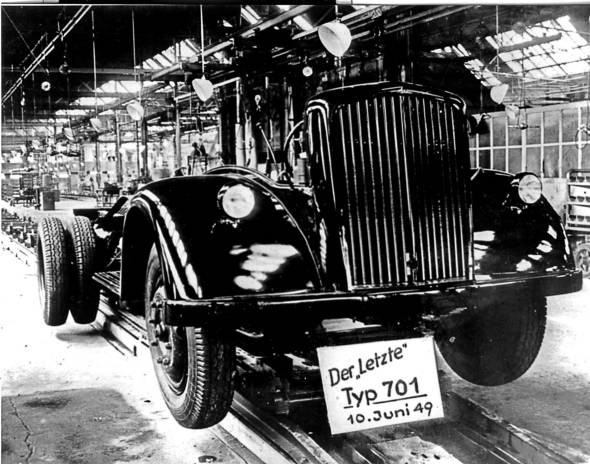

From 1948 Opel once again began supplying the original steel cab, which gave the L 701 a much more civilian appearance. But its days were numbered. The following year, on 10 June 1949, with total production having reached 10,300 units, the last L 701 came off the Mannheim production line to make way for its successor, the L 3250.

From problem child to everybody’s darling

The new L 3250 was clearly everybody’s darling, whereas the L 701, despite all its merits, had always been a problem child. In post-war years the L 701 had become a precarious affair if only for the reason that Opel had the right to terminate the licence agreement at any time with two years’ notice. This threatened to leave Daimler-Benz in a deeply compromised position.

For this reason, Wilhelm Haspel had raised the issue in the three-tonne debate as early as 1945: “If our model should be delivered in two years’ time, then strictly speaking it needs to be production-ready today.” Haspel went on: “The three-tonne question is of the utmost gravity, which is why we must deal with it in the most concrete of terms.”

In mid 1947 Opel finally terminated the agreement. The Daimler engineers then set feverishly to work adapting pre-war plans for a new diesel engine (OM 302) to the existing L 701 production. For it was clear that sooner or later Daimler-Benz would have to occupy the three-tonne segment with a product of its own.

Wilhelm Haspel had set out the dilemma back in 1945: “First we must we deal with the idea …of freeing ourselves from our shackles as Daimler-Benz. There will have to be a three-tonner at some point to which we can once again pin the Daimler-Benz brand. We need back our freedom to act.”

Direct model for the successor

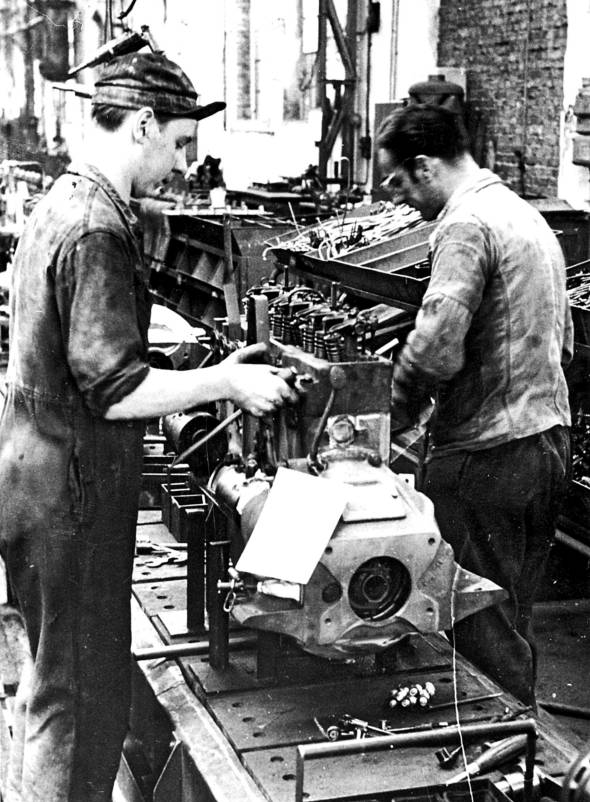

Although an amicable extension to the agreement was concluded with Opel for the time being, it did not alter the fact that achieving release from the dependency of this licensing arrangement was of the utmost urgency. And remodelling an engine that had been designed in the early 1940s so that it fitted seamlessly into current production was no mean feat. In terms of block length, for example, it had to match approximately the dimensions of the relatively short and narrow petrol unit. When the OM 302 was then forced to adopt the petrol engine’s irregular cylinder spacing, it gave rise to the new OM 312 – an engine series which had an extremely promising career ahead.

But much work needed doing. Instead of holes for the spark plugs, holes needed cutting for the glow plugs; and instead of a four-bearing crankshaft, a seven-bearing unit was required (to cope with higher pressures in the diesel engine). To make matters worse, the supply situation for coal, electricity and gas was nothing short of catastrophic in 1947. Production start-up planned for 1948 was moved further and further back. Opel extended the licence agreement until 1949 and from August 1948 began supplying once again the old steel driver’s cab for the L 701.

When its successor, the L 3250, finally reached series maturity in May 1949 and was presented at the Technical Export Fair in Hanover, it met with an enthusiastic response. A diesel engine with the power-to-swept-volume ratio of a petrol engine – and a diesel truck with load capacity of a petrol truck – were a great and most welcome surprise.

The L 3250 receives a warm welcome

The diesel truck, for which the L 701 licensed version of the Opel Blitz had been the driving force, was an outstanding vehicle. The

95-millimetre stroke of the petrol engine became a 120-millimetre stroke in the OM 312; and with the bore remaining identical at 90 millimetres, this increased the 3.6-litre displacement of the original petrol unit to 4.6-litres in the diesel. The new diesel engine had an output of 66 kW, compared with the 55 kW of the petrol version in the L 701. The L 3250 could handle a payload of 3.5 tonnes, whereas the L 701 had never managed more than 3.3 tonnes.

So it was no wonder that the L 3250 not only turned heads at its presentation, but also went on to enjoy a long and successful career. In Germany it was a bestseller, on international markets it was a number one export, and it helped established in no uncertain terms the Group’s global presence in the commercial vehicle sector.

With its rather underwhelming standard army driver’s cab, the L 701 has been referred to in some quarters as the ugly duckling. Nevertheless, without this Opel Blitz reproduction the L 3250 would never have been what it was at its Hanover debut in 1949.

Time runs out for the Blitz

Although this was not quite the end for the Opel Blitz, its days were strictly numbered following cessation of Mannheim production in June 1949. Opel built a further 467 Opel Blitz units in Rüsselsheim from 1950 to 1954 using pre-manufactured parts (and powered by the six-cylinder petrol engine from the “Kapitän”). But there was no successor. Pending a suitable diesel unit, time had run its course for the petrol engine in medium-duty commercial vehicles.