Autumn 1936: Mercedes-Benz sets new speed records

372.102 km/h with the power from twelve cylinders

A new record-breaking vehicle with a streamlined body and fully faired wheels as well as a likewise new V12 supercharged engine rated at 453 kW (616 hp): thus equipped, Rudolf Caracciola, the 1935 European Grand Prix champion, set out in autumn 1936 to break records for Mercedes-Benz.

His mission was a successful one. On 26 October 1936, the racing driver recorded a record speed of 372.102 km/h. And on 11 November 1936, he set a new world record of 333.489 km/h over 10 miles with a flying start.

In total, Caracciola bettered five existing international Class B records for vehicles with between 5 and 8 litres displacement and set one new world record.

Stuttgart. Record runs over various distances with both standing and flying starts had been a fixed part of the annual racing calendar since 1934 and the then-introduced 750-kilogram racing formula.

They served as proof of technological expertise and were attentively followed by the public. In 1936, the year of the Olympic Games in Berlin, Daimler-Benz, the inventor of the automobile, celebrated its 50th anniversary.

Traditionally committed to the concept of competition, the company additionally brought out a sensational record-breaking car in the autumn. Its strongest competitor, Auto Union, was just five years old.

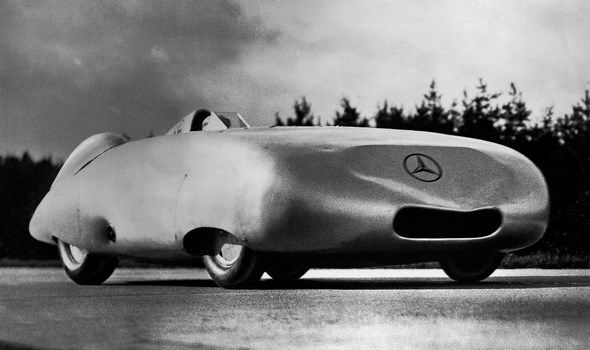

The runs on 26 October 1936 – described as “tyre tests” in the press invitation at the time – took place on the Frankfurt–Heidelberg autobahn, which is today the A5.

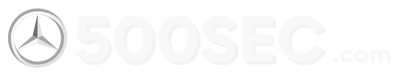

Whereas the record-breaking vehicles of previous years had been racing cars with fairing and modified bodies, Rudolf Caracciola in 1936 found himself at the wheel of an entirely new vehicle that the Mercedes-Benz engineers had designed exclusively with record-breaking runs in mind.

It was based on the chassis of the first “Silver Arrow” racing car W 25. However, the streamlined body was sleeker than before, and the wheels were extensively integrated into the body.

The idea came from the young designer Josef Müller. After a meeting in the wind tunnel at the airship builder Zeppelin in Friedrichshafen, in January 1935 he wrote a memorandum with a clear conclusion: in future, it would be indispensable for the wheels of high-speed vehicles to be integrated into the body.

For his test runs, Caracciola had a choice of two different windscreens. Due to the better visibility, he opted for the flat one rather than the curved one.

Another innovation was the 12-cylinder supercharged engine with a displacement of 5.58 litres and an output of initially 453 kW (616 hp).

The new V12 powerplant offered a level of performance previously unattained, despite continuous further development, by the 8-cylinder in-line engine in the Grand Prix Silver Arrow on account of the restrictions imposed by the 750 kilogram formula.

In 1936, the output from the Grand Prix engine, which now had a displacement of 4.74 litres, was still 363 kW (494 hp). By contrast, the 12-cylinder engine with the slightly awkward in-house designation M 25 DAB offered an extra 90 kW (122 hp) of output, which put it in the range required for breaking records.

By early 1938, the Mercedes-Benz engineers had managed to raise the output to 562 kW (765 hp).

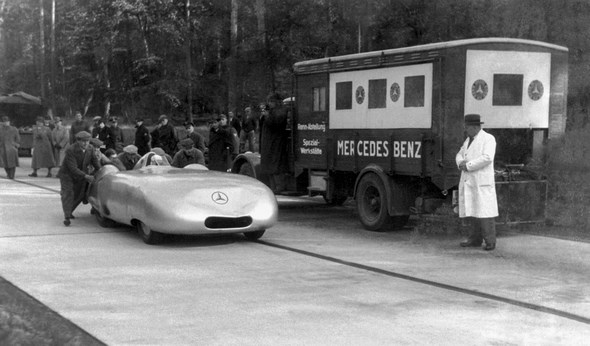

October 26 1936 was a day of great successes. A new class record of 364.38 km/h, as an average from both directions, was measured for one kilometre with a flying start.

This was despite the fact that the headwind on the first run had put a dent in the thin-walled body at the cooling-air inlet, thereby worsening the aerodynamics.

On the next run over one mile with a flying start, the average speed was 366.9 km/h, the absolute record of 372.102 km/h being measured on the return run.

For this test, there was also fairing on the rear wheels, a feature that was afterwards retained. On the previous runs, there had still been a small piece projecting from the body.

On the next run over 5 kilometres with a flying start, Caracciola improved the existing class record to 340.554 km/h (previously: 312.419 km/h). Wind then forced the record-making drives to be terminated.

They were resumed on 11 November 1936, by which time the vehicle had been given various improvements to transmission and body. After a first run, Caracciola decided against the closed cockpit that had been planned.

From the second run onwards, Caracciola once again drove with an open top. For the third run, the track was extended from 22 to 38 kilometres to accommodate the record attempts over 10 kilometres and 10 miles.

Caracciola significantly improved on the existing records. The outcome for Mercedes-Benz at the end of this second record-breaking day in autumn 1936: class record over 5 miles with flying start 336.838 km/h (previously: 291.035 km/h), class record over 10 kilometres with flying start 331.899 km/h (previously: 288.612 km/h), class record and also world record over 10 miles with flying start 333.489 km/h (previously: 285.451 km/h).

Yet another superlative: the record-breaking runs were filmed from an aeroplane flying above the autobahn – a sensation at the time.