New beginnings after the Second World War

- 1951: a time for testing and a new strategy

- Initial successes in 1952 with the Mercedes-Benz 300 SL (W 194)

- 1954 and 1955: triumphant years for the W 196 R and 300 SLR

The immediate priorities for Daimler-Benz AG in the initial post-war period were reconstruction and the resumption of production of passenger cars and commercial vehicles. A return to racing was not high on the agenda, and had to be a gradual process. Some post-war Mercedes-Benz 170 V passenger cars were already being made in 1946, but this model, which had already been in production from 1936 to 1942, did not have any potential as a racing vehicle. So in the first few years after the War, the former works drivers and design engineers from the racing department were spending their time repairing ordinary passenger cars – no easy task in the immediate post-war environment, and one which called on their considerable improvisatory skills developed from their years of manning the pits at racing events.

The company’s debut in post-war motor racing came in September 1950, when Karl Kling entered the ADAC six-hour race for sports and touring cars at the Nürburgring racetrack, in a Mercedes-Benz 170 S. A total of one hundred cars took to the track, after a Le Mans-style start. Kling described the race as follows: “On hearing the starter’s signal, I sprinted to my car as if I was Jesse Owens, tore the car door open, sat behind the wheel, started the engine, and was soon on the track, in a pack surrounded by all the other cars.” In spite of these efforts at the start, KIing came in only seventh for the up-to-2000 cc class.

Only after winning the Eifel race did Kling receive his long-coveted invitation to join the racing department re-established by

Mercedes-Benz in 1950 under the proven leadership of Alfred Neubauer. Approval for the return to motor sport was given by Wilhelm Haspel, General Manager of Daimler-Benz AG. Neubauer’s first attempt to return to the acme of motor sport was not far away, based on grand prix cars from the 1930s that were in good operational condition. Four W 154 vehicles and six racing engines provided enough components for the engineers to build three viable racing cars and four engines.

These cars were first put to the test in 1951, in two races in Argentina. Hermann Lang, Karl Kling and Argentinean driver Juan Manuel Fangio performed valiantly in Buenos Aires, with Lang and Kling both achieving second places, on 18 and 24 February 1951, respectively. But while these cars still had the speed to win, they were too heavy. Fangio himself was partly to blame. He had initially expected to be driving for Alfa Romeo, and therefore suggested a track with plenty of curves, to make life more difficult for the Silver Arrows, which were primarily designed for fast circular tracks – and then found himself driving for Mercedes-Benz.

These races in Argentina clearly demonstrated that the W 154 now had its best years behind it, and Neubauer’s plans for the Daimler-Benz racing department to enter the Indianapolis 500 mile event were shelved.

1951 also saw the launch of the first new post-war passenger car models, the 220 (W 187) and 300 (W 186 I). The 300 became the nucleus of the company’s motor sport successes over the next few years, as the basis for the 300 SL (W 194) sports car designed by Rudolf Uhlenhaut, followed by two production models: the ‘Gullwing’ coupe (W 198 I, 1954) and roadster (W 198 II, 1957). Before the War, Uhlenhaut had been Technical Manager of the racing department, and from 1949 he headed the passenger car development department.

Return of the Silver Arrow

On 15 June 1951, Daimler-Benz group management announced its plans to become involved in motor sport, including a focus on racing and sports cars. However, this did not extend to grand prix vehicles until 1954, when the new Formula 1 rules came into effect. The first Mercedes-Benz project was a new sports car. A design period of just nine months was enough to create the legendary 300 SL (standing for ‘sports light’).

The new car’s chassis was largely based on the Mercedes-Benz 300, with the brake linings extended to 90 millimetres. The main enhancements were to the six-cylinder inline engine, including three Solex down-draught carburettors and a more acute camshaft angle, boosting the power rating to 175 hp (129 kW) at 5200 rpm. The engine was inclined 50 degrees to the left in its support structure, a light tubular mesh frame.

This light and robust tubular frame extended well up the sides, for stability reasons. This was the origin for the 300 SL’s legendary ‘gullwing’ doors, since side-hinged doors would make it difficult to climb into the car over the high side structures. The doors initially ended at waist level, but from June 1952 they extended somewhat lower. The smooth contours of the body of the 300 SL and the narrow roof were a bold design move, as shown by the low cd value of 0.25. A maximum speed of 240 km/h opened up prospects for victories at international competition.

On 3 May 1952, two 300 SLs were entered in the Mille Miglia race. Karl Kling and Hans Klenk were second across the line in the 1000-mile event, with Rudolf Caracciola in fourth place. Not quite a victory, but Mercedes-Benz was the only brand to have two vehicles among the first five places. For racing manager Alfred Neubauer, a dream was coming true. “That day, I started to feel young again,” he later recollected.

Then, on 18 May, the 300 SLs scooped the pool in the Bern Prize for sports cars with a triple victory, with Karl Kling winning the race ahead of Hermann Lang and Fritz Riess. A first-second double in the famous Le Mans 24-hour race soon afterwards showed that the power of the ‘Gullwing’ car was matched by its stamina. The team of Herrmann Lang and Fritz Riess won the race ahead of Theo Helfrich and Helmut Niedermayr.

However, the result in the Bern race was overshadowed by the serious accident suffered by Rudolf Caracciola, owing to brake failure, ending his career. Caracciola was an exceptional driver in the history of Mercedes-Benz, a towering figure in the pre-war era during the time of the Kompressor cars (SW to SSKL models) and the Silver Arrow period, who again played a key role as a driver in the Stuttgart brand’s return to the racing arena in 1952.

The Anniversary Prize for sports cars on the Nürburgring racetrack in August saw the appearance of the 300 SL in a new format: four coupes modified as roadsters, one also with a slightly shorter wheelbase and narrower track width. The four cars duly took the first four places, in the sequence Hermann Lang, Karl Kling, Fritz Riess and Theo Helfrich.

An even greater sensation was the double victory of Karl Kling / Hans Klenk and Hermann Lang / Erwin Grupp in the Carrera Panamericana in November 1952 in distant South America. The exotic aura associated with long-distance racing was highlighted by the Kling / Klenk team’s legendary collision with a vulture, breaking the windscreen. From then on, the 300 SL windscreen was protected by mesh screen.

A comprehensively reworked version of the 300 SL for the 1953 season was quickly developed, but never used, since, during 1953, all efforts were focused on preparing for the return to grand prix racing in 1954.

1954: Formula 1 racing with the W 196 R

While the 300 SL was winning races, the Stuttgart team was already working on the return to grand prix racing, on the basis of major changes to Formula 1 specifications announced by the FIA (Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile) for the 1954 season. This was an ideal time for the re-entry of Mercedes-Benz, since other manufacturers would also have to develop new cars. The displacement restrictions were now a maximum of 750 cc for supercharged engines, and 2.5 litres for aspirating engines.

The objectives finally announced at the beginning of 1953 by Fritz Könecke, Chairman of the Board of Management of Daimler-Benz AG, were ambitious indeed: twin world championship titles for

Mercedes-Benz works drivers, in Formula 1 and the sports cars racing season.

This programme was to be coordinated by Hans Scherenberg as the design manager. The men responsible for achieving these demanding targets were Fritz Nallinger as chief engineer, Rudolf Uhlenhaut as head of the test department and Alfred Neubauer as racing manager. The new racing department had its capacity boosted accordingly, eventually employing a total of over 200 staff. They were also able to call on the expertise of another 300 specialists in other departments of Daimler-Benz AG.

The 1953 year was dominated by the development of the new grand prix car, leading to the withdrawal of the racing department from other races during the season. The result of their labours was a new racing car, the W 196 R. The vehicle originally had streamlined fairings, and at the start of the season a maximum power rating of 256 hp (188 kW) from the 2496-cc aspirating engine with desmodromic positive control, with a maximum speed of around 260 km/h. The new Silver Arrows were on the starting line for the second European race of the year, the French grand prix. The fully faired W 196 R posted the fastest times in training, and at this debut at Reims on 4 July they surpassed the expectations of the public and their competitors alike – with a dual victory for the recently recruited Argentinean drivers Juan Manuel Fangio and Karl Kling.

This sensational result had a truly historical resonance, since, in Lyon, exactly 40 years previously, on 4 July 1914, the French Grand Prix had also been won by Mercedes cars, with Christian Lautenschlager, Louis Wagner and Otto Salzer filling the first three places, in that order. The focus now was on securing the 1954 world championship title for Juan Manuel Fangio. He had to be content with fourth place in the British Grand Prix at Silverstone, where there were some problems with the car in its initial, rather unprepossessing streamlined format. But Uhlenhaut had already fast-tracked the construction of the second variant of the W 196 R, this time with exposed wheels, and also new tyres, developed for Daimler-Benz by Continental.

For the remainder of the 1954 season, there was always at least one Silver Arrow driver on the grand prix winners’ podium. Fangio took the German, Swiss and Italian events, and there were place results for Fangio in Spain (third) and Hans Hermann in Switzerland (third). When he won the Swiss Grand Prix at Bern-Bremgarten on 22 August, Fangio had built up an unbeatable lead in the standings for the 1954 Formula 1 world championship.

1955: twin championships and ‘auf Wiedersehen’

In 1955, armed with the improved grand prix car and 300 SLR (W 196 S) racing sports car derived from it, the racing department set about the quest for the double title, seeking a repeat of the grand prix title, plus the sports car championship. With this aim in mind, Neubauer had recruited British ace driver Sterling Moss to complement the skills of Juan Manuel Fangio. Other drivers racing for Mercedes-Benz during the 1955 season included Peter Collins, Werner Engel, John Fitch, Olivier Gendebien, Hans Herrmann, Karl Kling, Pierre Levegh, André Simon, Piero Taruffi and Wolfgang Count Berghe von Trips.

The W 196 R raced in 1955 had been thoroughly reworked, in terms of both the engine and the chassis. Along with the long wheelbase model (2350 mm), there was now also a medium version with a 140-mm shorter wheelbase, and the ultra-short ‘Monaco’ design with a wheelbase of just 2150 mm. The car was now around 70 kilograms lighter, and also had 30 hp (22 kW) more power: at 8400 rpm, the engine of the W 196 R now developed 290 hp (213 kW), ultimately giving the car a maximum speed of around 300 km/h. The distinctive visual feature of the W 196 R in its second year was the air scoop on the bonnet, required because of the modified intake manifold.

The 1955 racing season opened with the Argentinean Grand Prix, won by Fangio in extremely hot conditions. And just 14 days later, on 30 January 1955, Fangio also took first place in the Buenos Aires Grand Prix. The race featured four Silver Arrow cars, powered with the three-litre engine that was to be fitted in the new 300 SLR racing sports car. Juan Manuel Fangio and Stirling Moss recorded a dual victory in what was virtually an extremely demanding ‘road test’ for the new engine, with Karl Kling in fourth place.

The 300 SLR made its racing debut on 1 May 1955 in the Mille Miglia. The name and the body of the new car were reminiscent of the 300 SL from 1952, but in engineering terms the vehicle was clearly derived from the current grand prix Silver Arrow racing car, and quite different from its similarly named predecessor. Four of the new cars lined up at the start, along with several Mercedes-Benz 300 SLs and even three Mercedes-Benz 180 D diesel sedans. Juan Manuel Fangio was generally regarded as the favourite, but it was the young Englishman, Stirling Moss, with co-driver Denis Jenkinson, who took the event as the first non-Italian winner since Rudolf Caracciola (who won in 1931 in a Mercedes-Benz SSKL). Moss also recorded the best-ever time for the Mille Miglia: ten hours, seven minutes and 48 seconds, at an average speed of 157.65 km/h. Fangio took second place, and Mercedes-Benz won both the overall title and two categories: GT cars with displacement of more than 1300 cc, and the diesel class.

The short-wheelbase version of the W 196 R started in the Monaco Grand Prix, but Mercedes-Benz was not successful on this occasion. The various wheelbase and body versions of the W 196 R provided a wide range of options, yet the bodies were actually interchangeable with just a few simple adjustments. Chassis No. 10, for example, now displayed in a new aluminium body, raced in 1955 with exposed wheels in the Argentinean and Dutch grand prix events and was used for training at Monza with a fully streamlined body. The variant used on a given occasion depended on the characteristics of the track and the individual preferences of the driver.

Technical features common to all versions included the swing axle with low pivot point and the eight-cylinder, 2496-cc engine. The desmodromic operation of the valves, with cam lobes and rocker arms, provided higher revolutions, along with improved safety and power ratings. Fuel supply to the cylinders was via an injection pump jointly developed with Bosch, operating at a pressure of 100 kilograms per cubic centimetre.

Following the disappointing results at Monaco, both the racing and sports cars were back at the top of their form in May and June: Fangio took the 18th Eifel race in his 300 SLR, with Moss in second place, and won the Belgian Grand Prix in the W 196 R. This triumph was followed by a disastrous accident in the Le Mans race of 1955, in which three 300 SLRs were entered: as Jaguar driver Mike Hawthorn braked to go into the pits, he obstructed Lance Macklin (Austin Healey).

Macklin veered to the left, straight into the path of Pierre Levegh’s 300 SLR, who collided with the rear of the Austin, projecting the vehicle towards the grandstands. The engine and front axle came away from the rest of the car, and flew into the crowd.

The result was the worst accident in motor sports history, claiming 82 lives and injuring another 91 spectators. The race was continued in spite of the accident, to prevent access for the rescue services from being blocked by the departing public. After midnight, Daimler-Benz made the decision to withdraw the 300 SLRs from the event as a sign of respect for the victims. Accordingly, Moss and fellow-team member Simon were called into the pits.

The memory of the disaster remained a shadow hanging over the rest of the season – but the racing went on. In June, the Netherlands Grand Prix resulted in another double victory for Fangio and Moss in their W 196 Rs. The up-and-coming star Moss then won the English Grand Prix in a short-wheelbase W 196 R, followed by Fangio, Kling and Taruffi. This was an absolute sensation for the local public, since he was the first-ever English driver to win his home grand prix.

The Swedish Grand Prix for sports cars was won by Fangio, ahead of Moss, both in 300 SLRs, and Karl Kling complemented their double victory by winning the sports cars category in his 300 SL. One of the two racing sports coupes designed by Rudolf Uhlenhaut was also on hand in Sweden, and used during training for the race. The 300 SLR coupes were originally intended to start in the Carrera Panamericana, but this race was not held in 1955. The Gullwing coupe was seen on the track during training on several occasions, but never actually raced. One of these cars later became a favourite company car for Rudolf Uhlenhaut.

The final performance of W 196 R cars on the racing scene was in the Italian Grand Prix on 11 September. And because four events had been removed from the season calendar, this was also the first appearance of the streamlined, faired version of the car in 1955. All other races had been contested with open-wheel cars. The Monza track had been extensively modified, and was now very much a high-speed course, with each lap tantamount to two straight drives past the grandstands.

This meant high average speeds for the race, and, accordingly, Neubauer decided that Fangio and Moss would race in the faired monoposto design, with a long wheelbase. Kling was to drive an open-body medium-wheelbase variant, and Taruffi a short-wheelbase ‘Monaco’ car, also with an open body. Fangio was a clear winner for Mercedes-Benz, followed by Piero Taruffi just 0.7 seconds behind. The Argentinean master driver ended the season with 40 points, with a third Formula 1 world championship. Stirling Moss was the runner-up with 23 points.

However, the racing department’s second goal for the 1955 season was still a long way off. As Alfred Neubauer later recalled: “The only cloud on the horizon was the likely failure to win the racing sports car championship, or ‘Constructors’ Prize’. This championship, introduced only in 1953, is awarded not to the winning drivers, but to the manufacturer that made their cars. Ferrari was well ahead in the standings, and it was going to take a miracle to overtake them.”

The 300 SLR had shown that it was extremely competitive in several races already, but neither the Eifel race nor the Swedish Grand Prix counted for the world championship. Everything now hinged on the Tourist Trophy in Northern Ireland and the Targa Florio on Sicily. On 17 September, three 300 SLRs lined up at the start of the race in Northern Ireland, and Neubauer’s miracle came to pass: Stirling Moss and John Cooper Fitch won the race, ahead of Juan Manuel Fangio and Karl Kling’s 300 SLR, and third place went to Wolfgang Count Berghe von Trips (racing for the first time in the 300 SLR, although he did have competition experience in the 300 SL), with co-driver André Simon.

But to take the world constructors’ championship, Mercedes-Benz still had to achieve the desired result in the Targa Florio in mid-October. They had to win the race, and arch-rival Ferrari must not do any better than third – an objective successfully achieved, with the assistance of an exhaustively resourced campaign. Eight racing cars, eight heavy-duty trucks and 15 passenger cars were unloaded from the ferry from Naples, along with a support team of 45 mechanics. Stirling Moss said that he had never seen such a level of preparation and attention to detail, and such a huge logistical effort.

Neubauer had pondered long and hard on his tactics for the race: “I had never planned a race so carefully and thoroughly. For that Targa Florio 1955, I drew one last time on all my knowledge and experience, all my tricks and my love of the game.” Perhaps the most important part of the plan may have been his strategy for the change of driver: rather than handing over after three laps, as was the normal practice, this time the Mercedes drivers were to change only after four laps. Uhlenhaut also strengthened the 300 SLR for this tough circuit.

The first car started at 7 a.m. on 16 October 1955. Stirling Moss was in the lead before falling back to third place after his 300 SLR left the road. The damage to the car was clearly visible, but the mechanical systems were still fully intact. Peter Collins took over at the wheel, and promptly set a new lap record in the dented Mercedes-Benz.

He was back in the lead when he handed the wheel back to Stirling Moss, who won the event, 4 minutes and 55 seconds ahead of Juan Manuel Fangio. The third 300 SLR of John Fitch and Desmond Titterington came in fourth, behind Eugenio Castellotti and Robert Manzon (Ferrari 860 Monza). Mercedes-Benz had the dual victory it needed to win the work constructors’ championship – their goal had been achieved.

This marked the end of the triumphant Silver Arrow era: already before the tragic accident at Le Mans, Mercedes-Benz had decided that the racing department would close down at the end of the 1955 season. The commitment of effort and resources to the development and construction of the racing vehicles and supporting the campaign was huge. Daimler-Benz AG now felt that the talents of these outstanding engineers and mechanics was more urgently needed for the development of new passenger cars.

Technical Director Fritz Nallinger confirmed this decision at the function held to celebration the successful drivers’ achievement on 22 October 1955: “Given the growth in our product range, we believe the right approach now is to ease the load on these highly skilled specialists somewhat and allow them to focus all their efforts on the area that is most important for our customers all around the world – production car construction. The skills and experience my staff have gained from making racing vehicles will be put to good use in this capacity.”

This departure from the racing scene was the perfect example of ‘retiring at the top’: in 1955, the W 196 R racing cars had taken part in seven races, winning six first places, five seconds and one third. The 300 SLR racing sports car had started in six races, recording five victories, five second places and one third place. Mercedes-Benz’s domination of the season’s racing could scarcely have been more complete.

Further successes by works and private drivers of Mercedes-Benz vehicles made the record for 1955 even more impressive: Paul O’Shea (USA) won his first Class D sports car championship in the USA in a Mercedes-Benz 300 SL, defending that title for a further two years. Werner Engel won the 1955 rally championship in his Mercedes-Benz 300 SL, and Armando Zampiero was the Italian sports car champion in a Mercedes-Benz 300 SL.

But for the moment, the Silver Arrow era on the race track was over. It would only be many years later that Mercedes-Benz would return to the sports car championship and Formula 1 racing. Alfred Neubauer recalls a sombre leave-taking at the end of the season that had brought such outstanding success. The drivers pulled white cloth covers over the cars, and said their goodbyes. “We shook hands one last time – then they all went their separate ways – Fangio and Moss, Collins, Kling, Taruffi and Count von Trips. The adventure was over.”

1954: racing-car transporter – a unique product of the test workshop

The Silver Arrows were not the only hot topic on the racing scene in the early 1950s. Mercedes-Benz also made motor sport headlines off the circuit with the ‘world’s fastest racing-car transporter’. As part of the return to top-level motor sport, the Stuttgart team also had to set up the required service and repair operations at racing circuits, with workshop vehicles and transporters. Alfred Neubauer’s thoughts went back to 1924, when, at his suggestion, Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft had converted a large Mercedes touring car into a racing car transporter.

Neubauer’s idea was put into practice in the research section by master designer Hägele, the leader of a team of chassis fitters, engine specialists and bodybuilders responsible for making prototypes to drawings. The specified requirements for the racing-car transporter were brief and uncomplicated: it had to be fast, very fast – even with its load on board, i.e. a grand prix racer or SLR racing car. That meant plenty of power, with brakes to match.

The one-off design was built with tried and proven components: the 300 S contributed its X tubular frame as the basis for the structure, the powerful engine was taken from the 300 SL and the designers used components from the 180 model. The result was a visually and technically unique vehicle with a 3050-mm wheelbase. This was truly a ‘racing’ transporter, reaching speeds of 160 to 170 km/h, depending on the cargo.

The remarkable high-speed transporter was ready for use by mid-1954, painted in characteristic Mercedes-Benz blue. The racing department used it mainly for special assignments, for getting a car to the racetrack quickly after last-minute changes and adjustments, for example. Or it could be called on to take a damaged or faulty car back to the factory as quickly as possible, to leave more time for repairs. The racing-car transporter became a favourite beside the race track and a sensation on Europe’s roads and motorways. After autumn 1955, it was even borrowed for a tour through the USA, and it was featured in a number of exhibitions.

The intention was to place it in the Mercedes-Benz Museum of the day, along with the 300 SLR already on display there. However, the combination of the two vehicles would have exceeded the load-bearing capacity of the building, so the vehicle did valiant service for road-testing purposes, before being scrapped in December 1967 on instructions from Uhlenhaut.

In 1993, it was decided to rebuild the unique vehicle – a project involving almost 6000 hours of work. Experts spent seven years mulling over the details, designing the steering and transmission geometry and cable harness, building the rear window of the cab and finalising panelwork details. By 2001, the transporter was back, in all its former glory. Today, it has found a place in the new Mercedes-Benz Museum – with a 300 SLR on board.

Rallies and records

- Rally series victories with near-production Mercedes-Benz passenger cars

- Record drives with the C 111 in the years from 1976

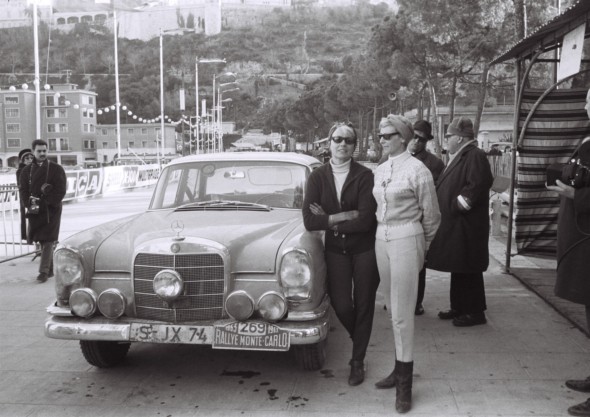

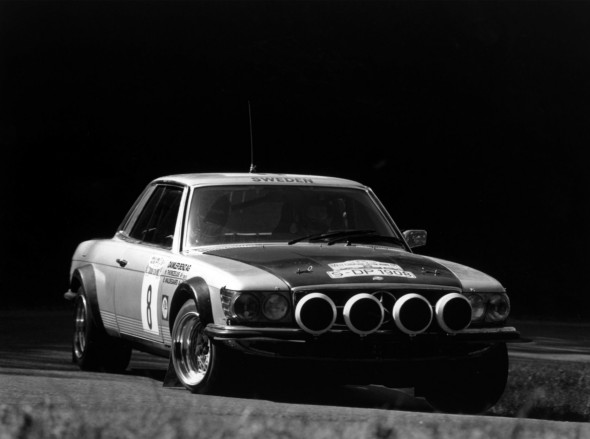

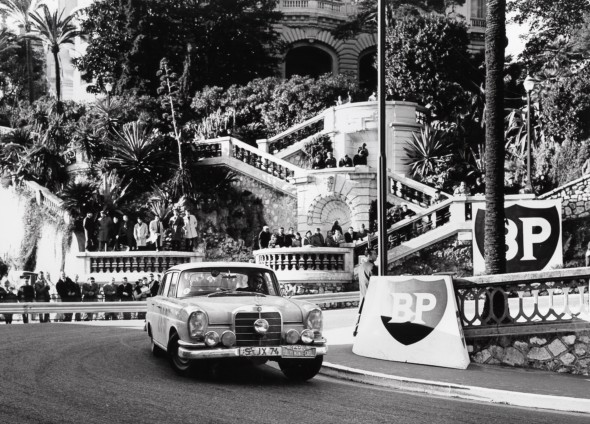

Rallies also occupy an important place in the Mercedes-Benz tradition – as in January 1952, for example, when Karl Kling, Rudolf Caracciola and Hermann Lang competed in the Monte Carlo rally in three Mercedes-Benz 220s (W 187). The Stuttgart trio came away from the event with the trophy for the best team performance.

This rally was an exciting challenge in particular for Kling, who had acquired his initial motor sport experience in long off-highway drives. However, this form of competition was far less popular with the German public than circuit racing, as the driver acknowledged: “A car race is tied to a circuit, with dramatic and sensational events unfolding before the eyes of the public, like the audience at a play. Thundering engines form the acoustic backdrop to an absorbing struggle between the drivers of these beautiful cars, the thoroughbreds of the automotive world.

The battle of man at the steering wheel versus matter is played out on centre stage. A rally is different – the event takes place over wide spatial expanses, with the drivers locked in a grim struggle with the caprices of the weather and the route. Their struggle is with themselves, with fatigue, monotony and hundreds of kilometres of back-country roads, over hilly and flat sections of the course, or along the coast. This is a hidden struggle, lasting minutes, hours or even days at a stretch.”

Mercedes-Benz vehicles had already enjoyed success in rally events during the Silver Arrow era from 1952 to 1955, in the hands of private drivers such as fruit and vegetable merchant Walter Schock. He entered the first Solitude Rally, on 24 and 25 April 1954, in his business vehicle, a Mercedes-Benz 220a (W 180 I). That year’s event counted towards the German touring car championship, and included a slalom course at Malmsheim airport and acceleration and braking trials in the Stuttgart urban area. Uniformity trials were held between these various points. A total of 174 entrants started from eleven different locations towards the Solitude castle, where the special stages were to begin.

Schock won the event, and with co-driver Rudolf Moll went on to achieve many more rally victories over the next few years in Mercedes-Benz vehicles. In 1954, he also won the Wiesbaden Rally, the Weinheim Spring Drive and the Bavaria Rally. The duo then entered what was probably the leading European rally, the Monte Carlo event. In 1955, the Schock / Moll team received only limited support from Mercedes-Benz for this adventure. Racing manager Alfred Neubauer had a bigger objective in view for that season – winning the ‘double’ of the Formula 1 world championship and sports car championship.

He also still had bitter memories of the racing department’s experience from the Monte Carlo rally in 1952. The test workshop did, however, optimise Schock’s privately owned Mercedes-Benz for the rally by lowering the body setting.

The race started on 17 January – and the Stuttgart duo proceeded to take third place in the overall rankings after the four days of the event. This was followed by a victory in the Sestriere Rally in Italy (25 February to 1 March 1955), second place in the Adriatic Rally in Yugoslavia (20–24 July 1955), and fourth place in the Viking Rally in Norway (9–12 September 1955). Walter Schock was also back on the starting line for the Solitude rally in 1955, this time coming third. This event had now become a true endurance rally, over a distance of 2000 kilometres.

1956: focus on rally events

Following the withdrawal of the Mercedes-Benz works team from Formula 1 and the sports car championship, from 1956 all eyes were on the rally scene. Mercedes vehicles, mainly driven by private teams, were competing on rally courses all around the world. Whereas the racing cars and racing sports cars from the years before had shone as top-performing thoroughbreds, it was now the turn of near-production passenger cars to show their strength and stamina. The man responsible for rally operations was Karl Kling, now in the role of Mercedes-Benz director of motor sport, taking over some of the responsibilities of legendary racing manager Alfred Neubauer following the latter’s retirement.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, it was mainly the 220 SE and 300 SE six-cylinder sedans and the 300 SL sports car that set the pace on the world’s roads and gravel tracks. One of the leading teams was the already well-known duo of Walter Schock and Rudolf Moll, racing for the Stuttgart Motor Sports Club. Extensive support was now forthcoming from Mercedes-Benz in the form of vehicles and service. Schock started in the Monte Carlo Rally in a Mercedes-Benz 220a on 15 January, finishing on 23 January only 1.1 seconds behind the winner.

One month later in Italy, the competition simply had no chance. The Stuttgart duo started the Sestriere Rally on 24 February in a Mercedes-Benz 300 SL Gullwing coupe, and in the mountains the Silver Arrow left the rest of the field far behind. Schock recollections of the outstanding performance of the coupe in the winter rally conditions as follows: “Very fine snow chains on all four wheels allowed us to reach uphill speeds of up to 180 km/h.” And on 28 February, the team drove across the finish line as the event winners.

Further triumphs followed, with victories in the Wiesbaden Rally (21–24 June 1956), the Acropolis Rally (25 April to 2 May 1956) and also first place in the Adriatica Rally. Schock and Moll also finished third in the Iberico Rally and tenth in the Geneva Rally. In addition, Schock won the Eifel race, and was placed second in the 1956 Nürburgring Grand Prix. He was the international rally champion for 1956, as well as being European touring car champion and German car champion in the GT up to 1300-cc class.

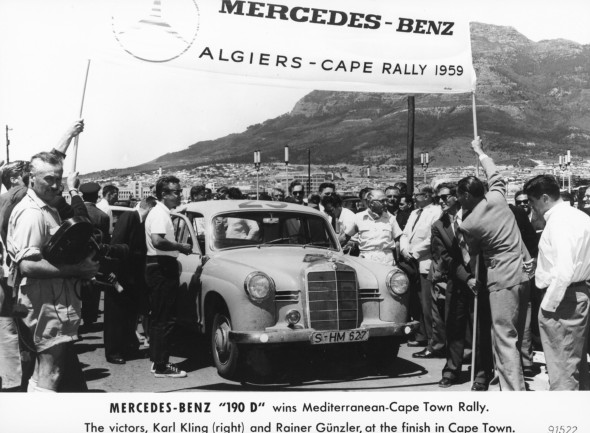

1959: motor sport director Kling stands in as works driver

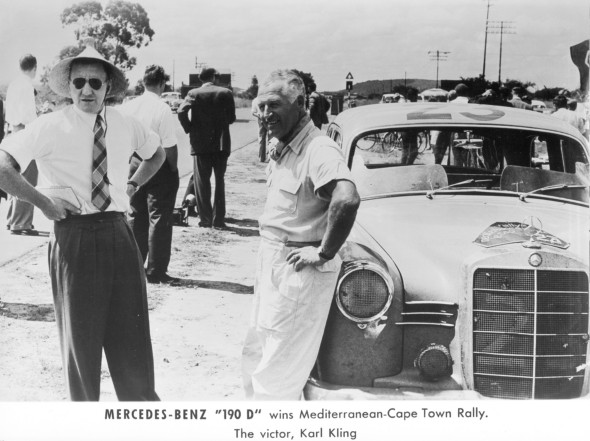

The motor sport director himself occasionally took a turn at the wheel as a member of the works team – and Karl Kling, with Rainer Günzler as co-driver, actually won the 14,000-kilometre Mediterranée-Le Cap rally in this way in 1959. The Stuttgart team were driving a diesel-powered Mercedes-Benz 190 D, whose reliability secured the event for them. Kling was back at the wheel of a sedan in 1961, when he drove a Mercedes-Benz 220 SE to victory in the Algiers-Lagos-Algiers rally in Africa, again with Rainer Günzler as co-driver.

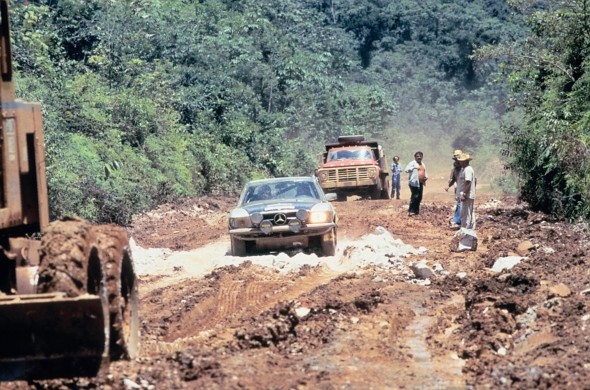

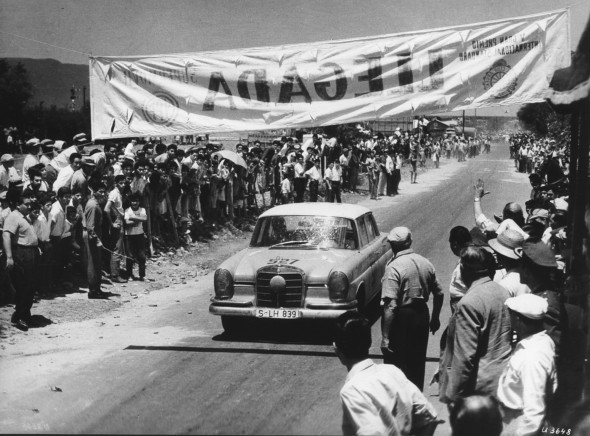

Kling also acted as racing manager when Mercedes-Benz works teams were competing in particularly large races. This included accompanying his teams on several occasions in the 1960s to the Argentinean Open-Road Grand Prix. On 26 October 1961, Walter Schock was one of the 207 drivers starting in this very special rally. The competitors knew they had a tough race ahead of them, over a distance of 4600 kilometres with an altitude difference of around 3000 metres between the highest and lowest points on the route.

The event ended on 5 November with a double victory for Mercedes-Benz. Walter Schock and Rolf Moll finished first, followed by Hans Herrmann and Rainer Günzler in second place. “That was probably the toughest race I have ever driven”, Schock said on his return from South America. Juan Manuel Fangio himself was on hand with racing manager Karl Kling to support the teams backed by the Stuttgart brand.

In 1962, it was again Schock and Moll who won the European rally championship in their 220 SE, taking first place in both the legendary Monte Carlo rally and the Acropolis rally in Greece. Their first victory at Monte Carlo had been in 1960, which was also the first time a German team had won the event outright.

Mercedes had actually made a clean sweep of all three places, with Eugen Böhringer / Hermann Socher second and Eberhard Mahle / Roland Ott third. Following this triumph in 1960, there had been loud calls in the sports press for the continued participation of Mercedes-Benz works vehicles on the world’s race circuits. But Karl Kling as motor sport director left the company’s position in no doubt: “This success will encourage us to continue our intensive efforts in the rally arena. However, Mercedes does not intend to intend to return to motor racing.”

In the years up to 1964, various drivers – including at least one female team (Ewy Rosqvist and Ursula Wirth) – continued to win numerous rally and racing events in ‘tailfin’ models. Another extremely competitive vehicle at this time was the Mercedes-Benz 230 SL, or the ‘Pagoda’, as it was often known. This was the vehicle driven to victory in the Liège-Sofia-Liège marathon rally in 1963 by Eugen Böhringer / Klaus Kaiser, for example.

Mercedes-Benz was also enjoying considerable success in North America at this time, and in 1957 it actually created a car specifically for the American sports car championship: the Mercedes-Benz 300 SLS. The vehicle was based on the 300 SL production sports car, but its lower weight, at just 900 kilograms, and higher power, boosted from 215 to 235 hp (158 to 173 kW), resulted in a highly competitive car. The SLS gave American Paul O’Shea his third consecutive title, following victories with a 300 SL Coupe in the 1955 and 1956 seasons.

The big eight-cylinder 300 SEL 6.3 sedan was raced as a works vehicle only once – when it won the six-hour touring car race in Macao in 1968 for Erich Waxenberger. The oil crisis in the early 1970s barred further race outings for the sedan.

Automotive historian Karl Eric Ludvigsen emphasises the importance of this break in the motor sport tradition of the Stuttgart brand: “The oil crisis was the first externally prompted interruption to a long-established Daimler-Benz tradition, which had run continuously from the turn of the century, apart from the war years and a short hiatus in 1955: year after year, there had always been one or more Benz, Mercedes or Mercedes-Benz vehicles competing with direct or indirect works support in at least one major race.”

Even now, however, the Mercedes-Benz racing tradition was continued by private drivers. Their vehicles were increasingly being prepared for competition by AMG, a workshop established by Hans-Werner Aufrecht and Erhard Melcher in 1967. One of their standout products from the first few years was the refined version of the Mercedes-Benz 300 SEL with a 6.9-litre engine, which finished second in the 24-hour Spa race in 1971. AMG remained in operation for many years as an independent tuning specialist for the preparation of racing cars and touring sports cars, before being fully acquired by the then DaimlerChrysler AG.

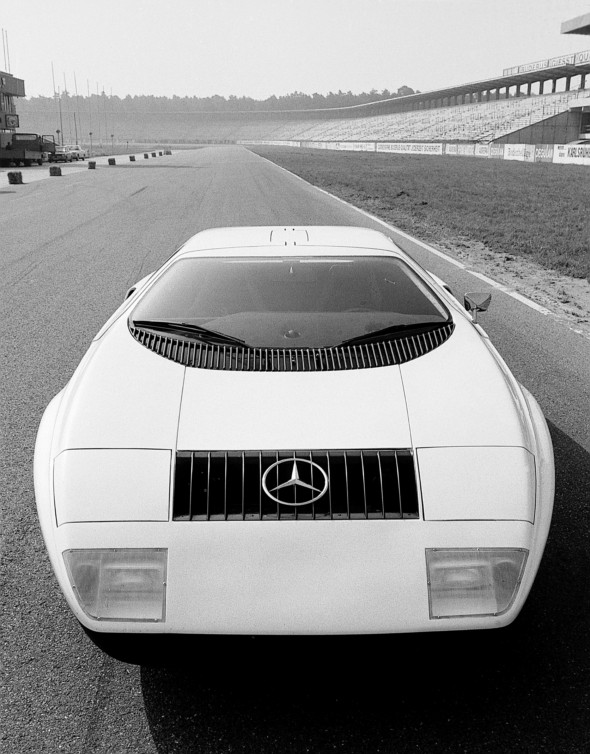

1976: record drives with the C 111

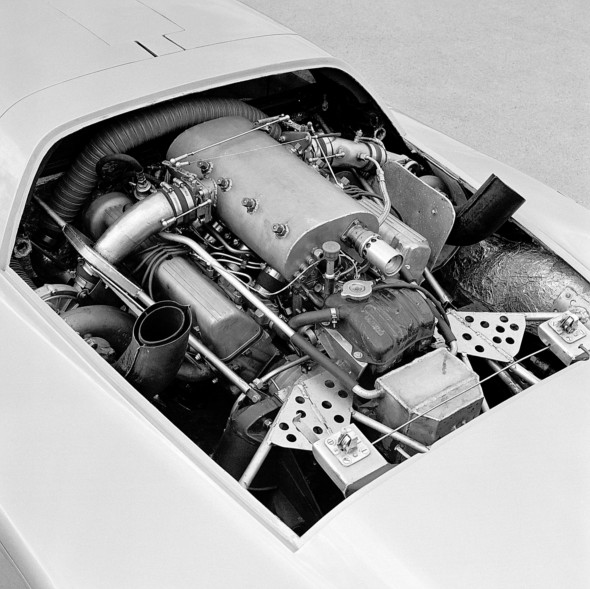

The rotary engine Mercedes-Benz C 111 coupe, launched in September 1969, was also affected by the impacts of the oil crisis. The futuristic experimental design featuring a three-disk rotary piston engine was much admired and envied throughout the automotive community, as a visionary successor to the 300 SL Gullwing car. The car was followed one year later by a reworked version with a four-disk rotary piston engine. It was this model that became the nucleus of the second Silver Arrow era.

Any dreams of further success in sports-car racing were to remain unrealised, however, and the C 111 remained as an extraordinary experimental car. One of the arguments against series production was the rotary engine’s appetite for fuel, and the relatively high levels of pollutants in the exhaust gas. In 1971, Mercedes-Benz therefore decided to stop work on this compact engine, in spite of its impressive power and quiet-running characteristics.

The exploits of the C 111 on the racetrack were rather in the area of the record drives carried out in the years from 1976 to 1979. In 1976, Mercedes-Benz decided to tackle the long-standing prejudice against diesel engines as rough and slow. And what better argument could there be than a diesel-propelled C 111? For the first test drives, the engineers built a three-litre diesel engine with five cylinders and exhaust turbocharging, fitted in an externally unmodified C 111-II.

In this car, known as the C 111-IID, a OM 617 LA production diesel engine – also used in the Mercedes-Benz 240 D 3.0 (W 115, ‘dash eight’) and subsequently other vehicles – developed a highly impressive 190 hp (140 kW), thanks to turbocharging and charge-air cooling. The standard production power rating was 80 hp (59 kW). In June 1976, the C 111-IID posted some spectacular speeds on the test track at Nardo in Italy.

A team of four drivers set a total of 16 world records in just 60 hours, including 13 for diesel vehicles and three for any form of engine. Given the average speed of 252 km/h,

Mercedes-Benz had proven beyond doubt that the diesel engine could also be a sprinter.

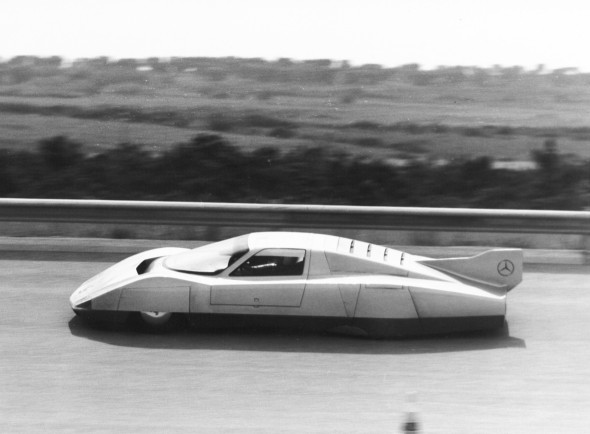

The triumph of the externally virtually unmodified C 111-II in Nardo spurred the designers on to new heights. The experimental design produced this time was never intended for use on public roads – the C 111-III was a ‘record car’ pure and simple, designed solely to break speed records. The new vehicle built during 1977 was narrower than the first C 111, with a longer wheelbase. Aerodynamics were enhanced will full fairing and tailfins.

The C 111-III returned to the Nardo track in 1978, again with a diesel engine rumbling beneath the plastic body, this time painted silver. This was still a production-based engine, but now with a power rating of 230 hp (169 kW), propelling the streamlined car to speeds of well over 300 km/h. Mercedes-Benz went on to post nine absolute work records with this Silver Arrow car in the late 1970s.

Yet this was just the beginning of the C 111’s development into a true record-breaking machine. The last version of the car, the C 111-IV launched in 1979, reached a speed of 403.978 km/h on the Nardo track, breaking the then world record. This time, however, the diesel engine had been replaced with a V8 petrol engine with a displacement of 4.5 litres and two turbochargers, developing 500 hp (368 kW). The body shape was now also far removed from the initial design. The bold, confident contours of the 1969 model had mutated ten years later into a lean, elongated racing body with two tailfins and massive spoilers, painted silver.

1978: the days of the V8 coupes and debut of the 190

The reappearance of Mercedes-Benz on the motor sport winners’ list came only in 1977, when the teams of Andrew Cowan / Colin Malkin / Mike Broad and Anthony Fowkes / Peter O’Gorman posted the fastest overall times in the London-Sydney marathon rally, driving a works-supported Mercedes-Benz 280 E. The same model was also entered as a works car in the East African Safari in 1978.

However, that year was dominated mainly by the fast V8 coupes: four Mercedes-Benz 450 SLC cars (C 107), with a power rating of 230 hp (169 kW) and automatic transmission, took part in the tough ‘Vuelta a la América del Sud’ rally in South America. The 30,000-kilometre race in August and September ended with a five-fold victory for Mercedes-Benz: the Cowan / Malkin and Sobieslaw Zasada / Andrzej Zembruski teams won in Mercedes-Benz 450 SLCs, followed by Fowkes / Klaus Kaiser (280 E), Timo Mäkinen / Jean Todt (450 SLC) and Herbert Kleint / Günther Klapproth (280 E).

The following year the same near-production car, now called the 450 SLC 5.0, with the rebored eight-cylinder engine developing 290 hp (213 kW), provided the performance needed for a quadruple victory in the 5000-kilometre Bandama rally in Africa.

The event was won by Hannu Mikkola and Arne Hertz, ahead of Björn Waldegaard / Hans Thorszelius, Cowan / Kaiser and Vic Preston / Mike Doughty. In 1980, Daimler-Benz entered the rally world championship in earnest, with a 500 SLC vehicle developing up to 340 hp (250 kW). Against tough competition, Waldegaard / Thorszelius and Jorge Recalde / Nestor Straimel posted another dual victory in the Bandama rally at the end of the season.

This was also the last works involvement of Daimler-Benz AG in rallying, since, in December 1980, the Board of Management decided that the firm would withdraw from the world championship for capacity reasons. However, the numerous rally victories achieved over a period of almost 30 years had successfully proven the performance capabilities of near-production Mercedes-Benz vehicles, making this facet of motor sport an effective brand ambassador in a particularly direct sense.

The 1983 Mercedes-Benz 190 E 2.3-16 Nardo record car was also based on a production vehicle. Mercedes-Benz put the modified 190 car through its paces on the Nardo racetrack in Italy as publicity for the launch of the W 201 model series, to highlight the sports performance capabilities of the new compact class sedan.

These record cars had a 2.3-litre engine with four-valve technology, developing 185 hp (136 kW) at 6200 rpm. Differences with the subsequent production version included the rear axle ratio (i=2.65) and the absence of a reverse gear. The record cars were also set lower, with all-round ride height control. Special tyres and spoilers enabled the compact sedan to reach a top speed of 261 km/h.

Test department employees notched up 201 hours, 39 minutes and 43 seconds of test drives in the three record cars – precisely 50,000 kilometres. In the process, they set three world records (25,000 kilometres at 247.094 km/h, 25,000 miles at 247.749 km/h and 50,000 kilometres at 247.939 km/h), and nine class records (including 1000 kilometres at 247.094 km/h and 1000 miles at 246.916 km/h). The record car based on the 190 2.3-16 also heralded the return of Mercedes-Benz to circuit motor racing in 1984.